William Kentridge

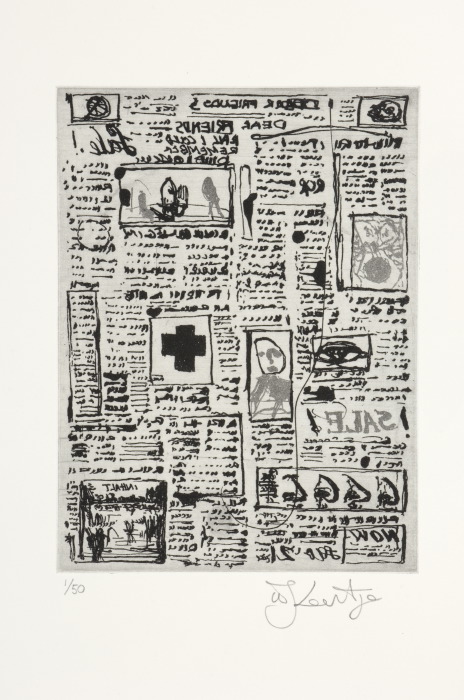

In 1997, the first major publication on Kentridge’s work was published in CD-ROM format by David Krut. Since then, David Krut Publishing has released numerous books about the artist’s work, including William Kentridge Prints in 2006, which is the first book to give an overview of Kentridge’s printmaking career up to that point.

In total, David Krut has published more than 300 print editions with Kentridge. Kentridge has had more than eight solo exhibitions with DKP and been included in many group exhibitions in Johannesburg, Cape Town and New York over the years.

For related videos, take a look at the William Kentridge Playlist on the David Krut Publishing & Projects YouTube Channel

- West Coast series,

- Kentridge does a DKW walkabout with Harvard University Art History postgrads,

- The Refusal of Time at The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

- Nose and Other Subjects travels to Syracuse University Art Gallery.

- Apollo Award Winners 2015,

- William Kentridge: Officially Africa’s Most Powerful Artist,

- Black & White: Interview with Kentridge,

- Kentridge plans massive, vanishing mural in Rome

- Ink | Thinking Aloud: The Prints of William Kentridge

- Billboard art makes the questions bigger

- William Kentridge: Star of the art world at Deichtorhallen

Artworks (347)

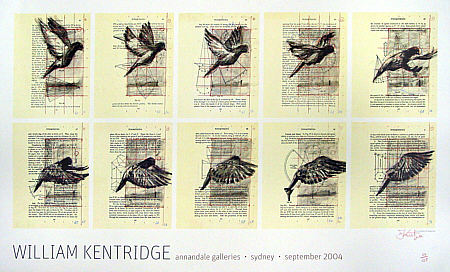

Posters

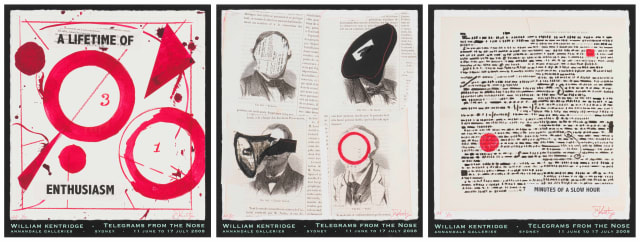

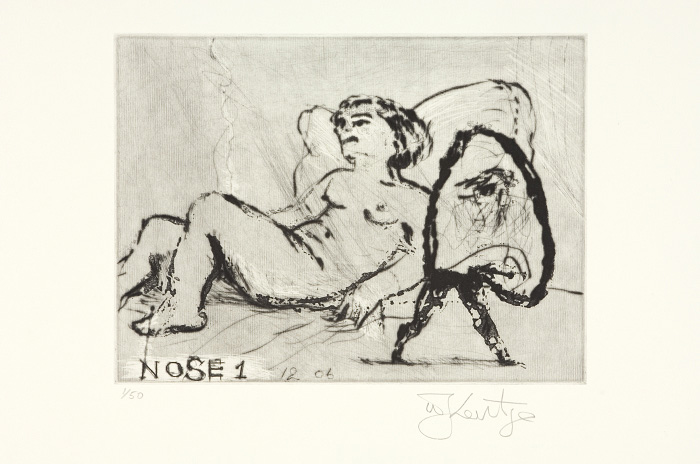

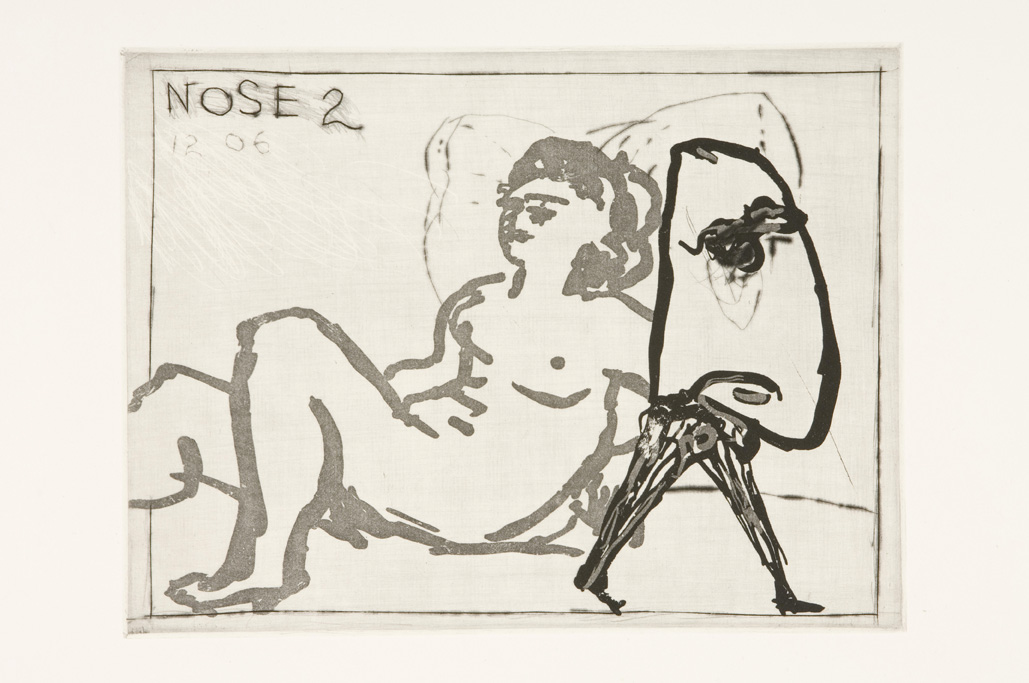

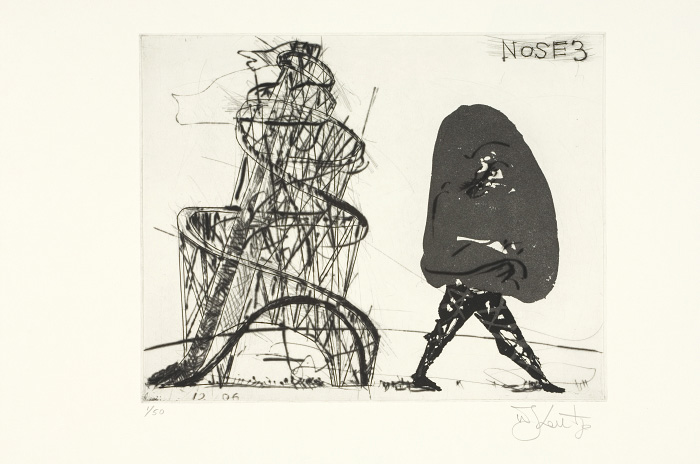

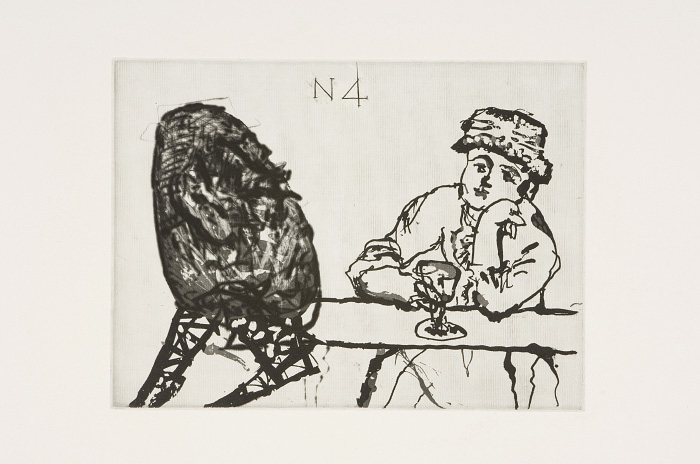

The Nose

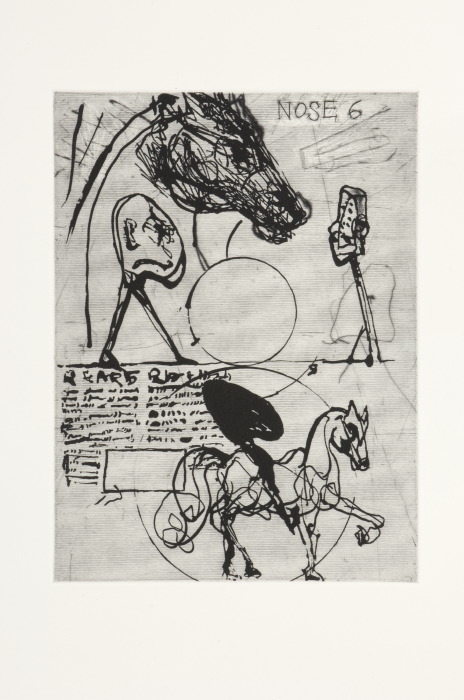

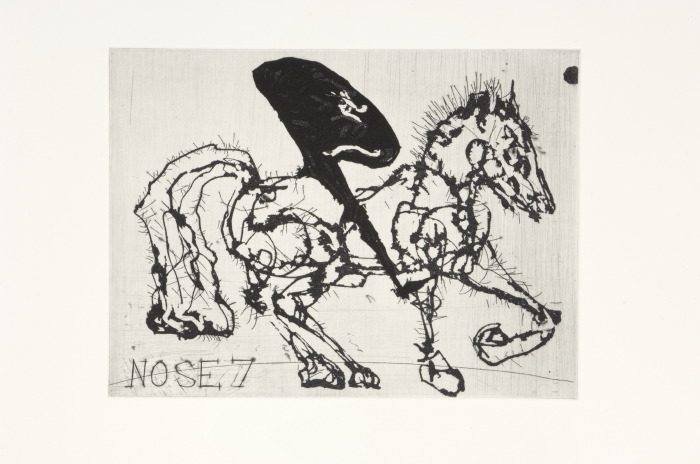

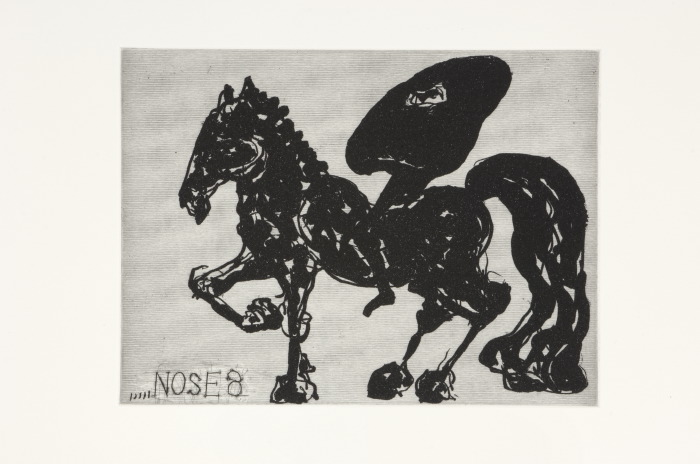

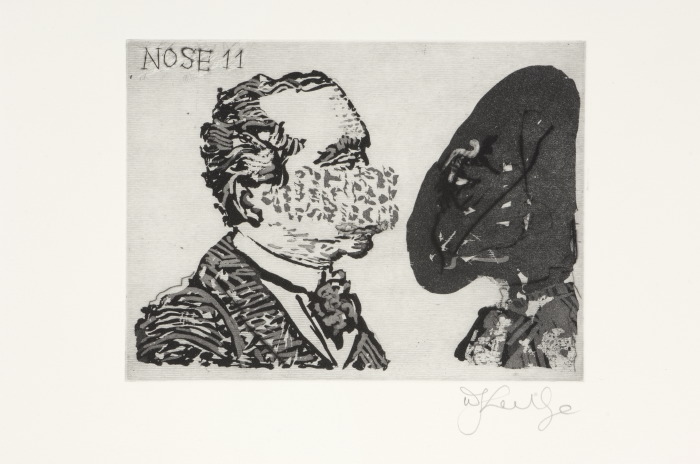

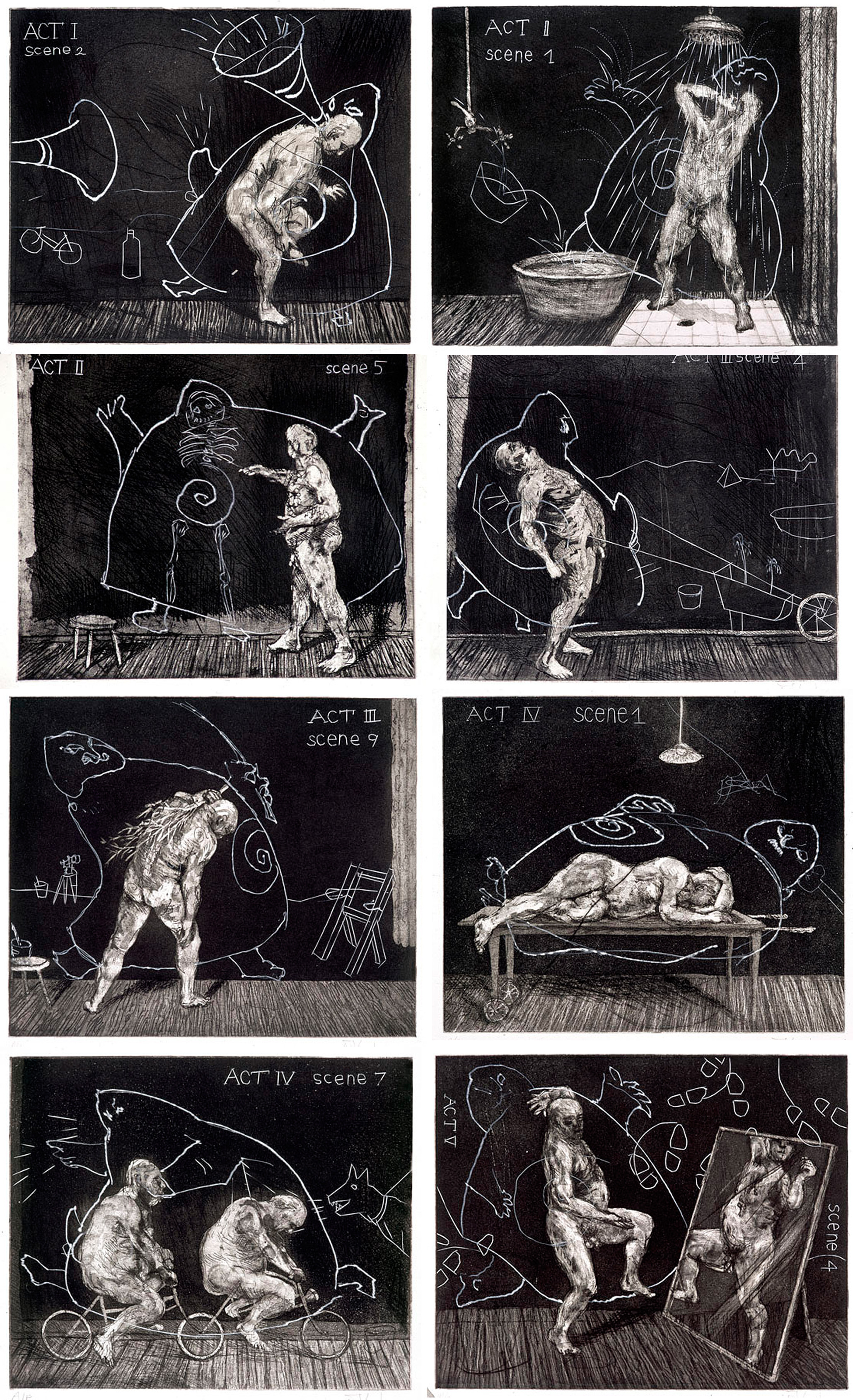

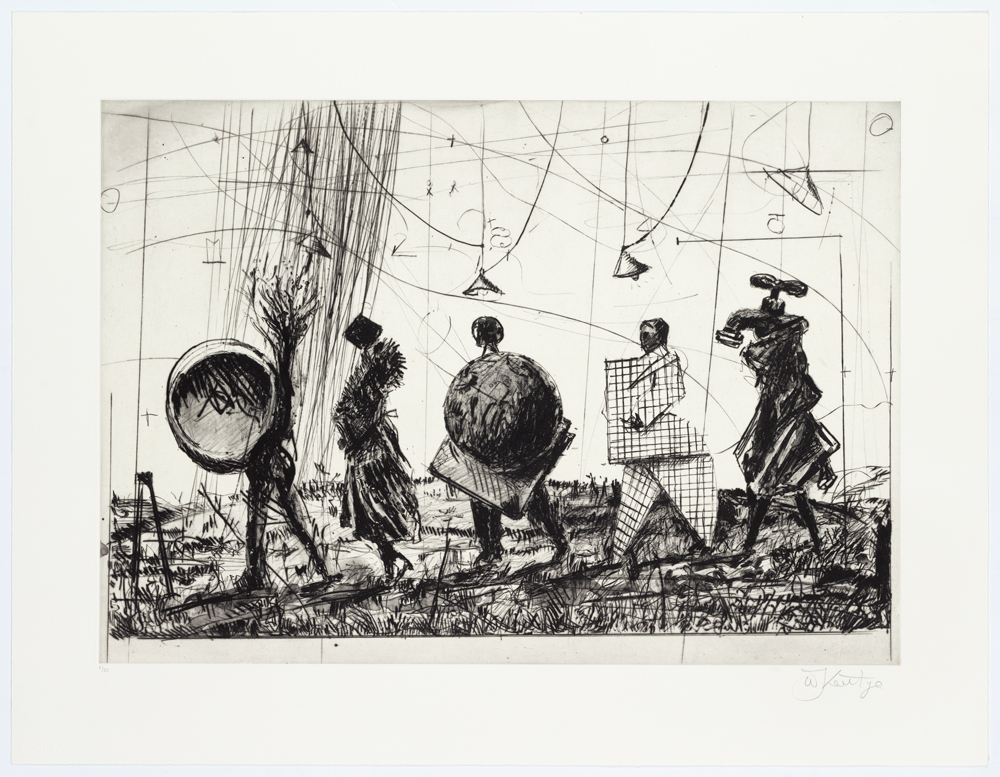

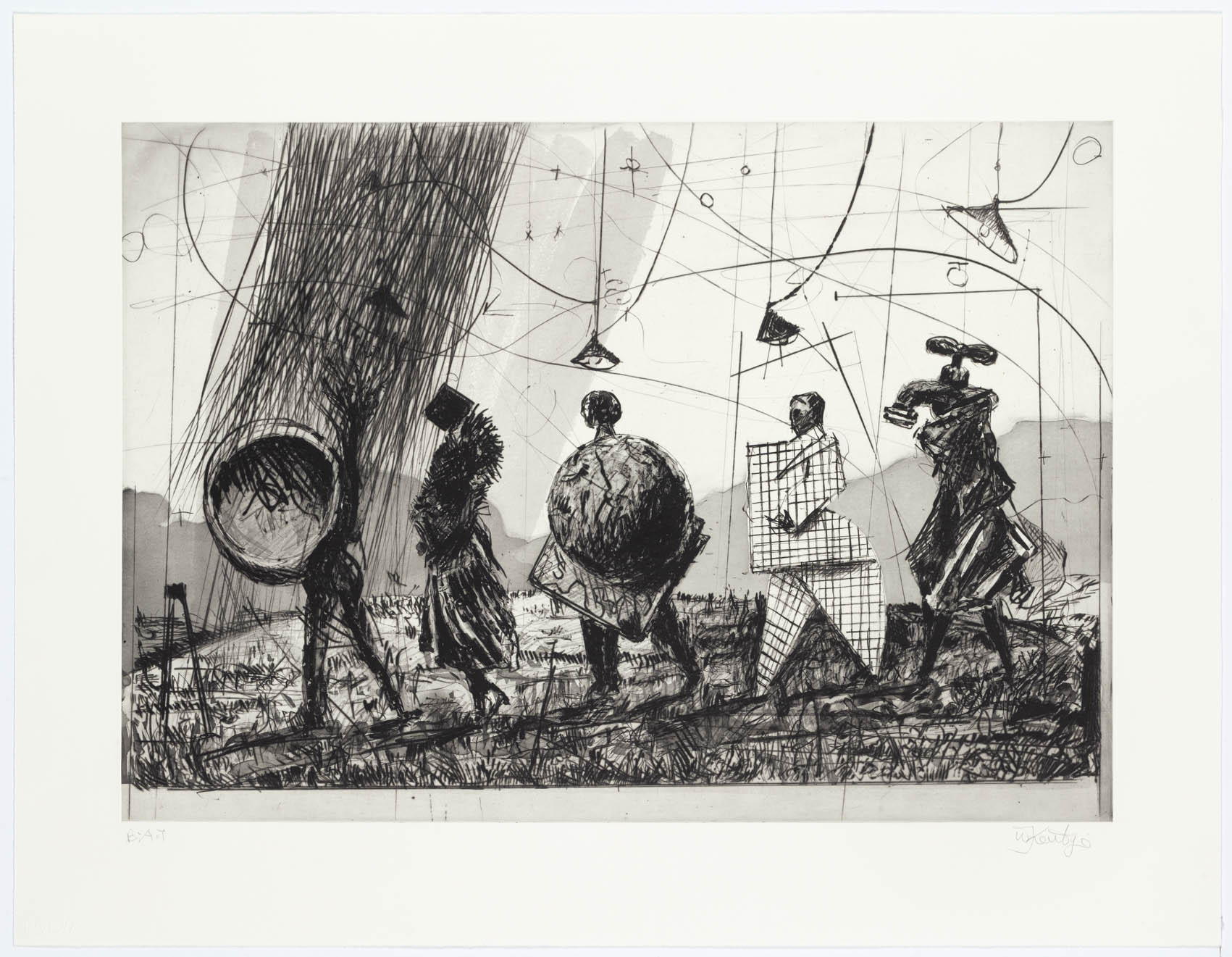

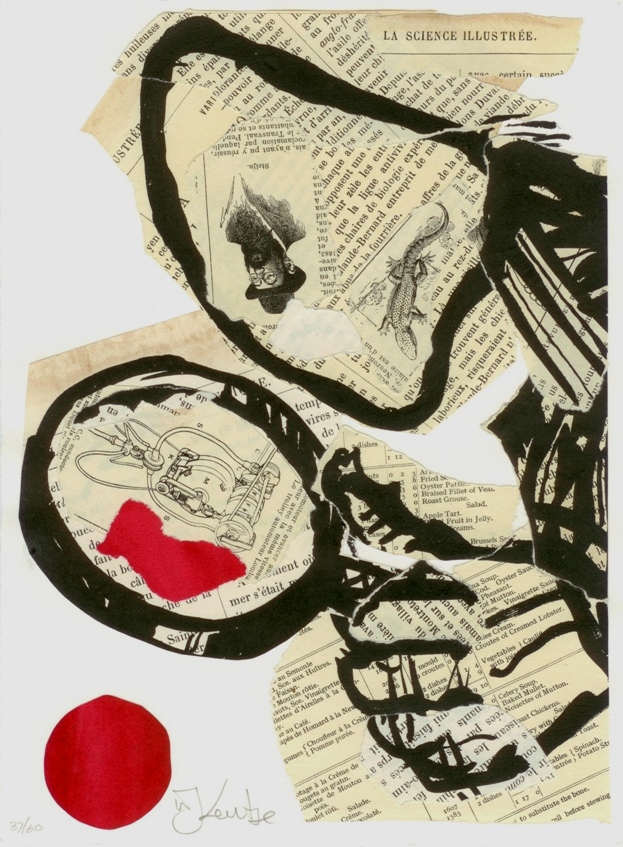

In December 2006 Jillian Ross, Master Printer of the David Krut Workshop (DKW), began her collaboration with William Kentridge on a series of prints that was to elaborate on Kentridge’s work on the Shostakovich opera The Nose, commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera, New York, to premiere in March 2010. Shostakovich’s opera is based on one of the most famous stories in Russian literature, Nikolai Gogol’s The Nose, published in 1867.

In William Kentridge Nose, published by David Krut Publishing in 2010, William Kentridge explains the story, and its relationship to the prints, as follows:

"In 1867, Nikolai Gogol published his short story The Nose. The story is about a middle-ranking Russian bureaucrat, Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov, who wakes one morning to find his nose missing. In its place is only a ‘pancake- smooth expanse’. The narrative follows Kovalyov’s attempts to locate and re-attach his nose. Anton Chekov described The Nose as the finest short story ever written.

Kovalyov wanders the streets of the city in search of his nose and eventually catches a glimpse of it entering a cathedral. He follows it inside and tries to reason with it and persuade it to return to him. But his nose is now a higher-ranking bureaucrat than he is and will have nothing to do with him. As The Nose goes its own way, Kovalyov is left to contemplate ‘that ridiculous blank space’ again.

This set of prints follows—or makes—the journey of the independent Nose."

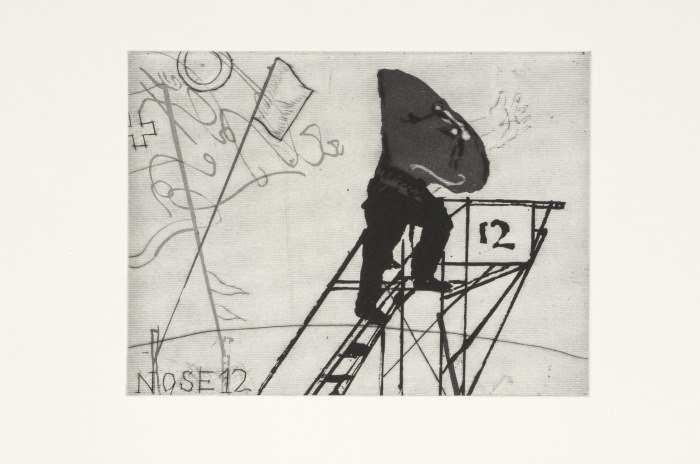

The prints reflect on music, ballet, the history of Western art and the various fortunes of the Communist parties in South Africa and the Soviet Union.

Read more ▼In his interpretation of Gogol and Shostakovich, Kentridge has projected the story forward to the 1917 Russian Revolution and the Russian avant-garde, and then into the twentieth century to include allusions to Stalin’s purges of the 1930s. But he has also cast his eye back to consider some of the literary influences on Gogol such as Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy and even Cervantes’s Don Quixote. Drawing on these and other texts, including excerpts from Russian newspapers, clips from Russian films of the 1920s and 1930s, pages from Russian encyclopaedias, and parts of a transcript of a 1937 meeting of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party in which the theoretician Nikolai Bukharin is being interrogated, Kentridge created not only his opera production but several other works, including the Nose suite of etchings.

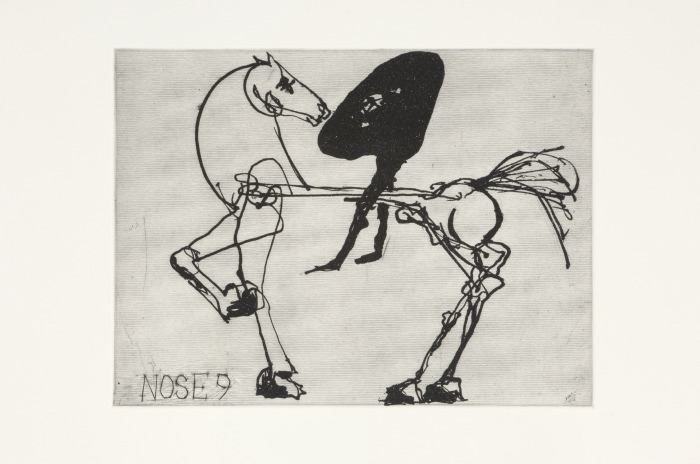

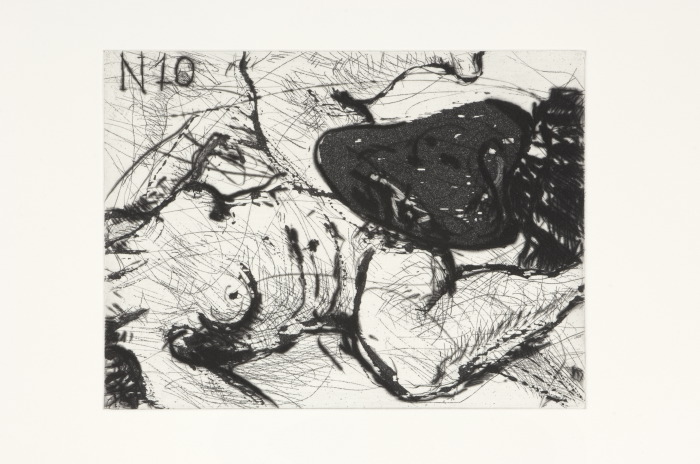

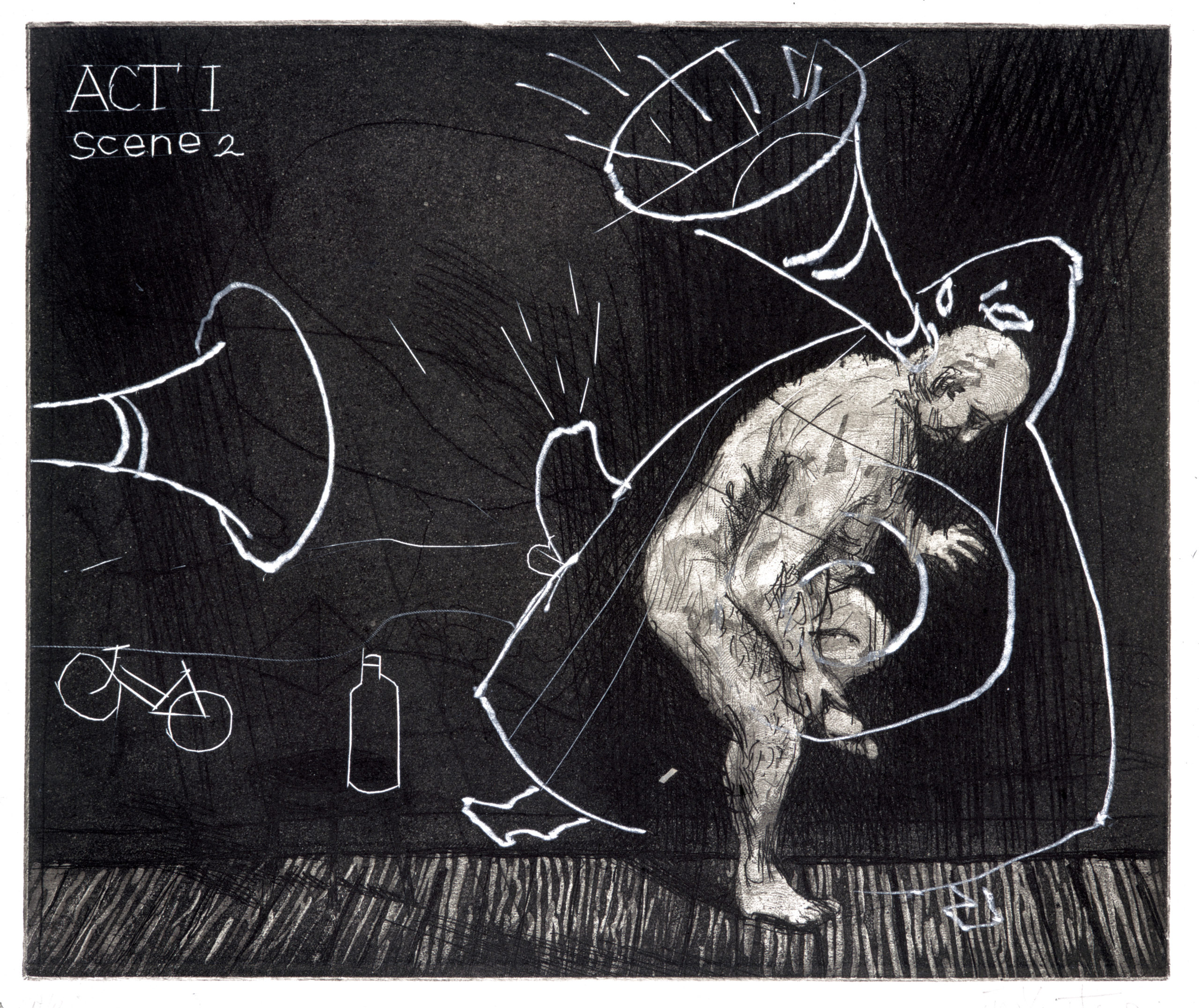

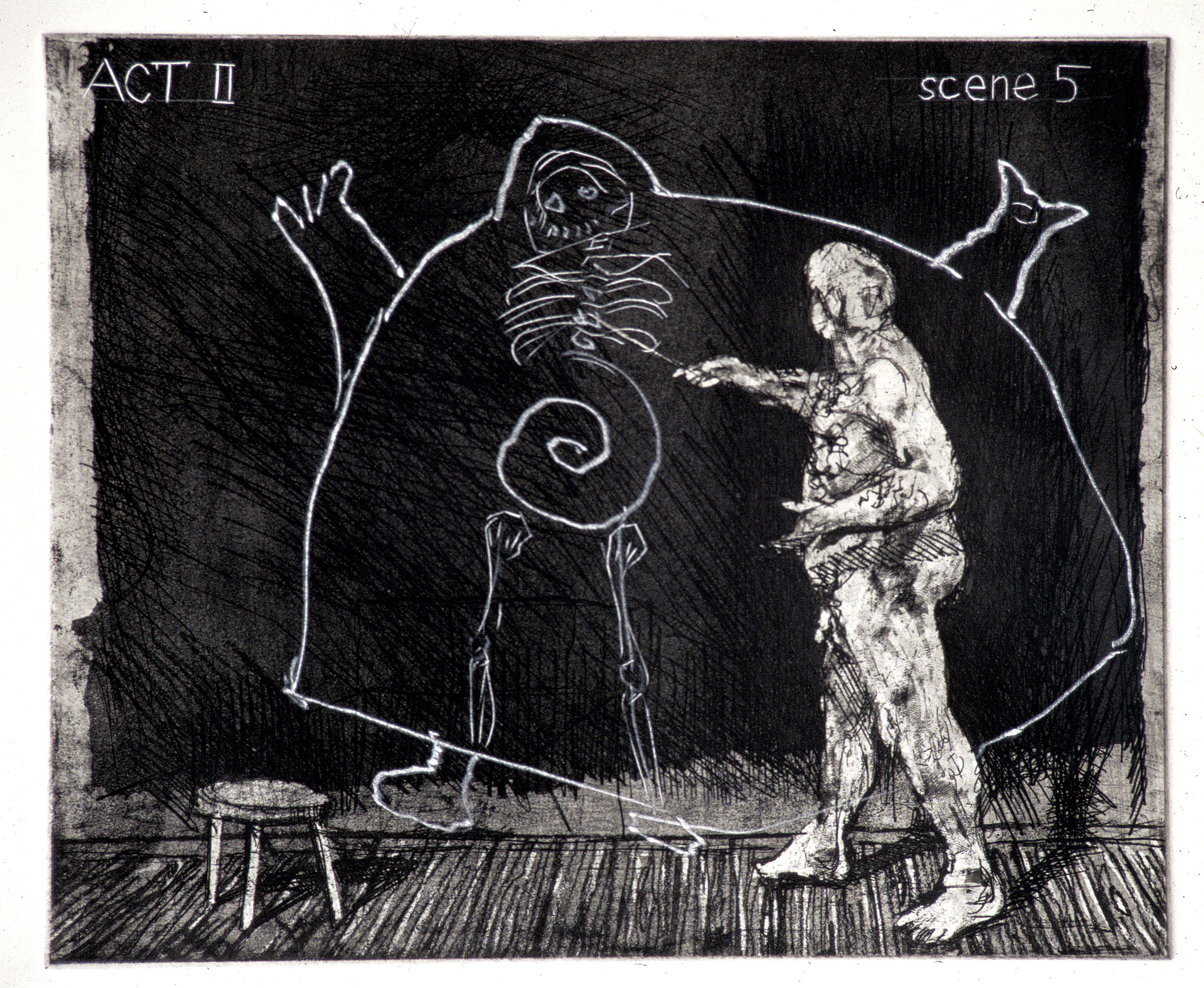

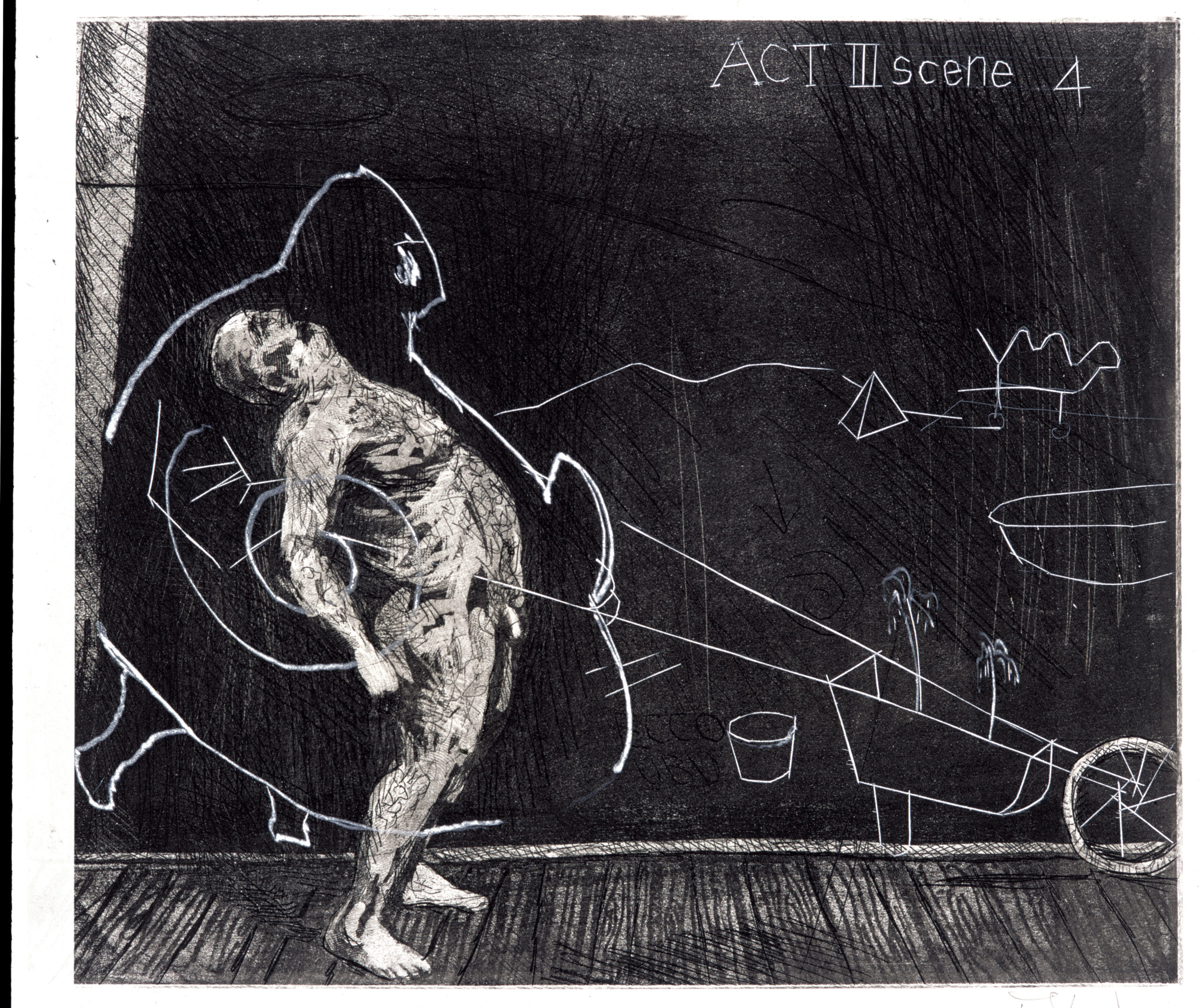

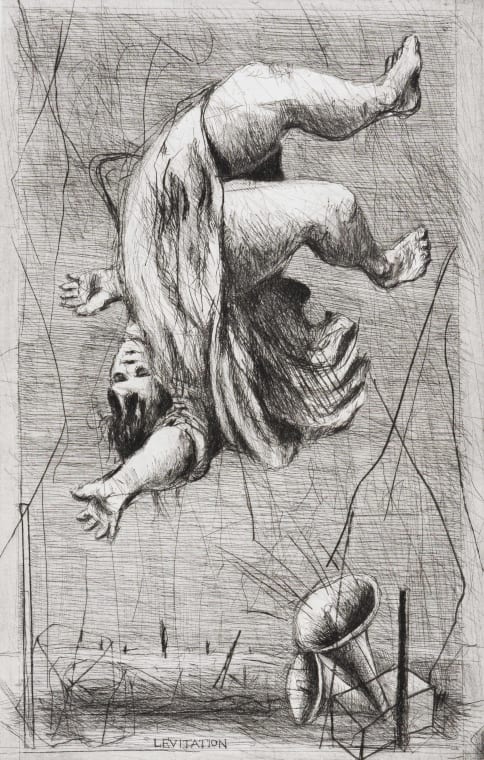

Nose is a suite of thirty prints, each measuring roughly 15 x 20 cm (5 x 8 in) and printed in an edition of 50. The prints explore a number of techniques but rely primarily on Kentridge’s strong drypoint marks, softened by sugarlift aquatint and punctuated, in several plates, by a strong Constructivist red. Each plate is engraved with a number signalling its place in the series.

Please note the following works are only available as part of the complete set of thirty prints: Nose 1,3,7,9,26,29 and 30.

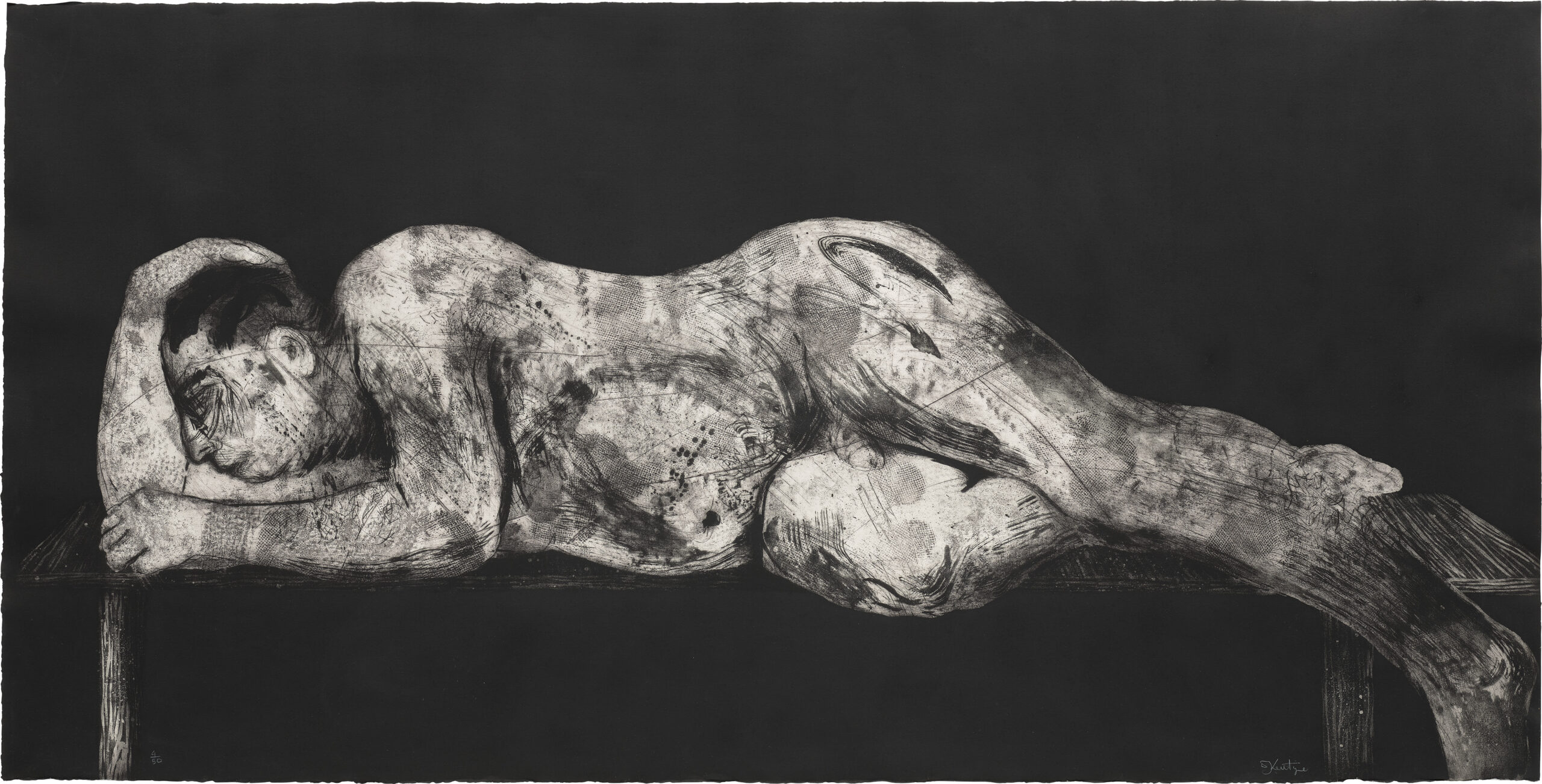

Five subsequent prints were published, known informally in the workshop as the “Nose Extras” – El Lissitky, Mirror, Odalisque, Chaise-Longue, and Nose on a White Horse. For various reasons, Kentridge did not consider these works a good fit for inclusion as part of the Nose suite of 30 etchings which, although each print is available individually, is designed to be understood as a single work in its own right. They were, nonetheless, well-loved by Kentridge and so they were published separately as stand-alone images.

Loading more artworks...

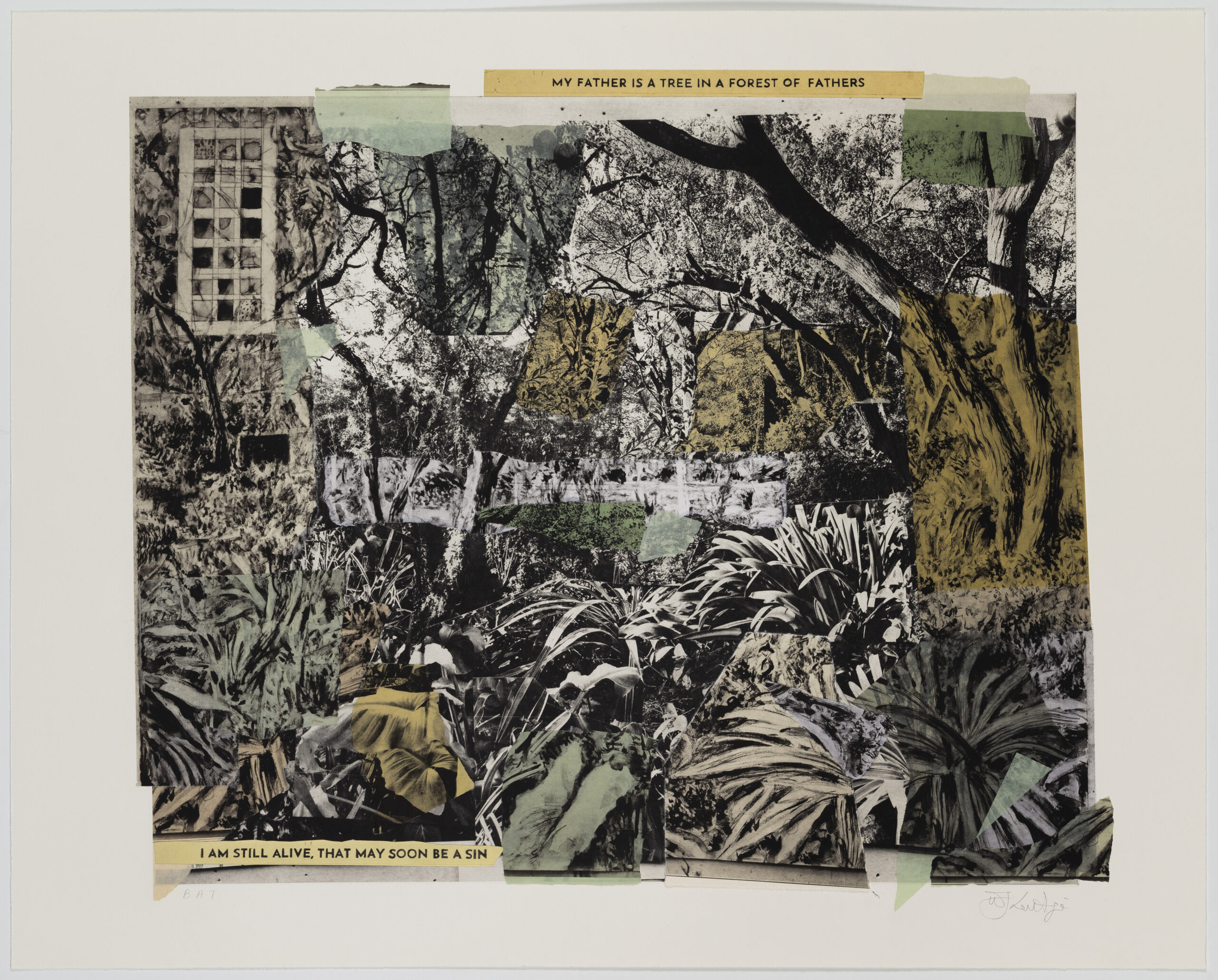

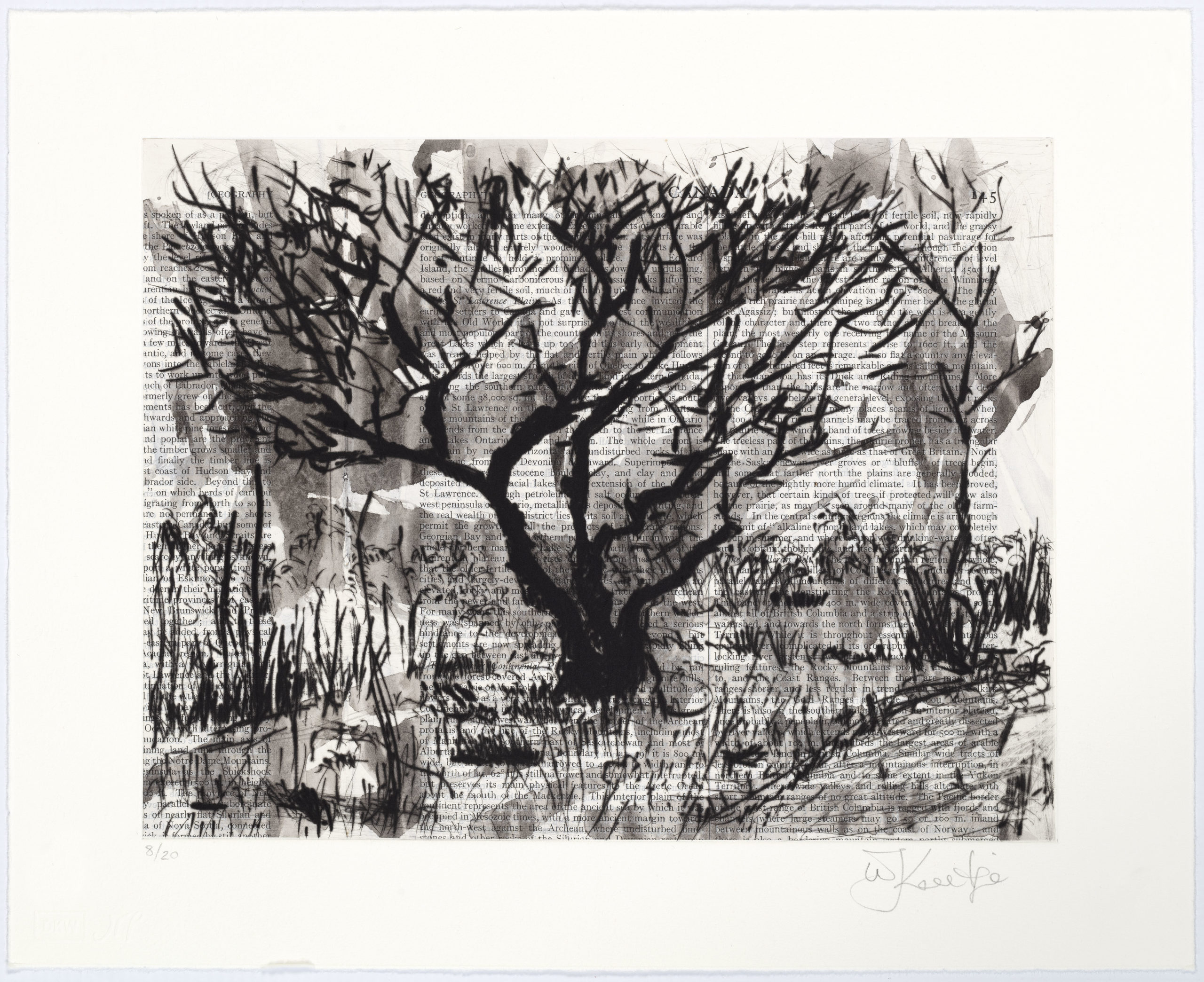

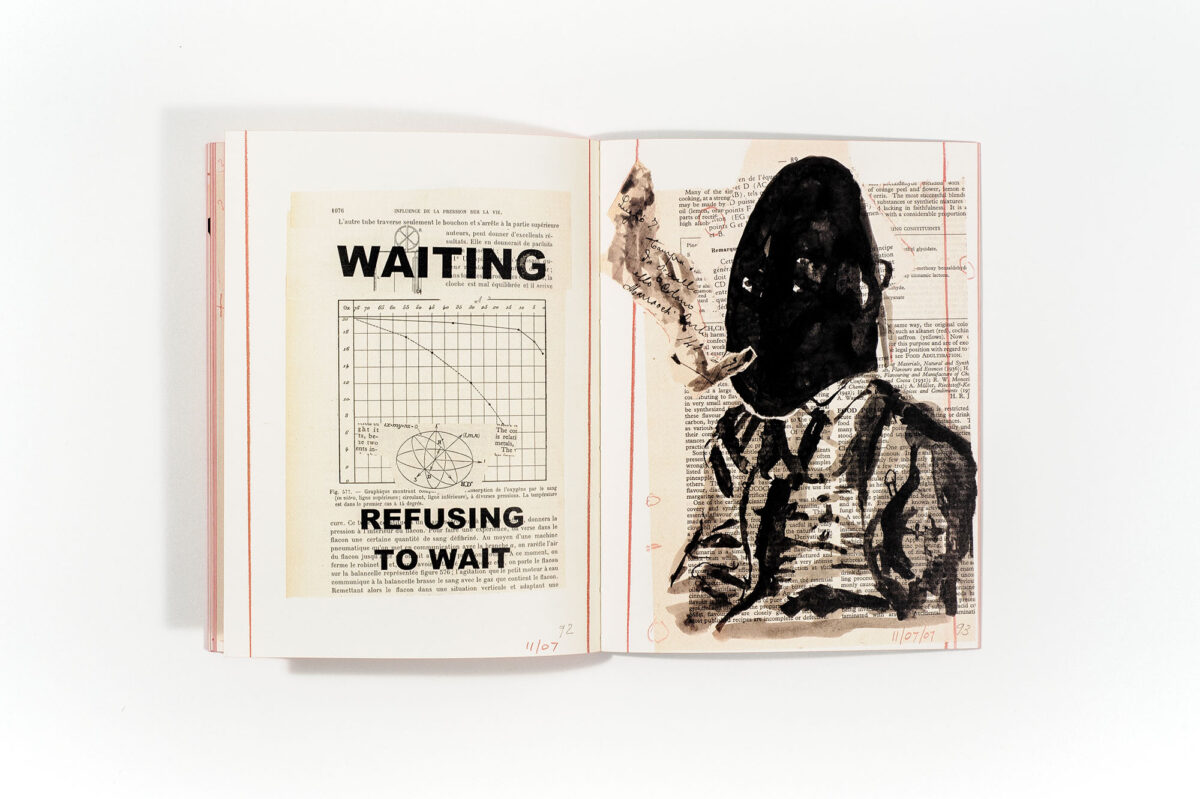

The Universal Archive

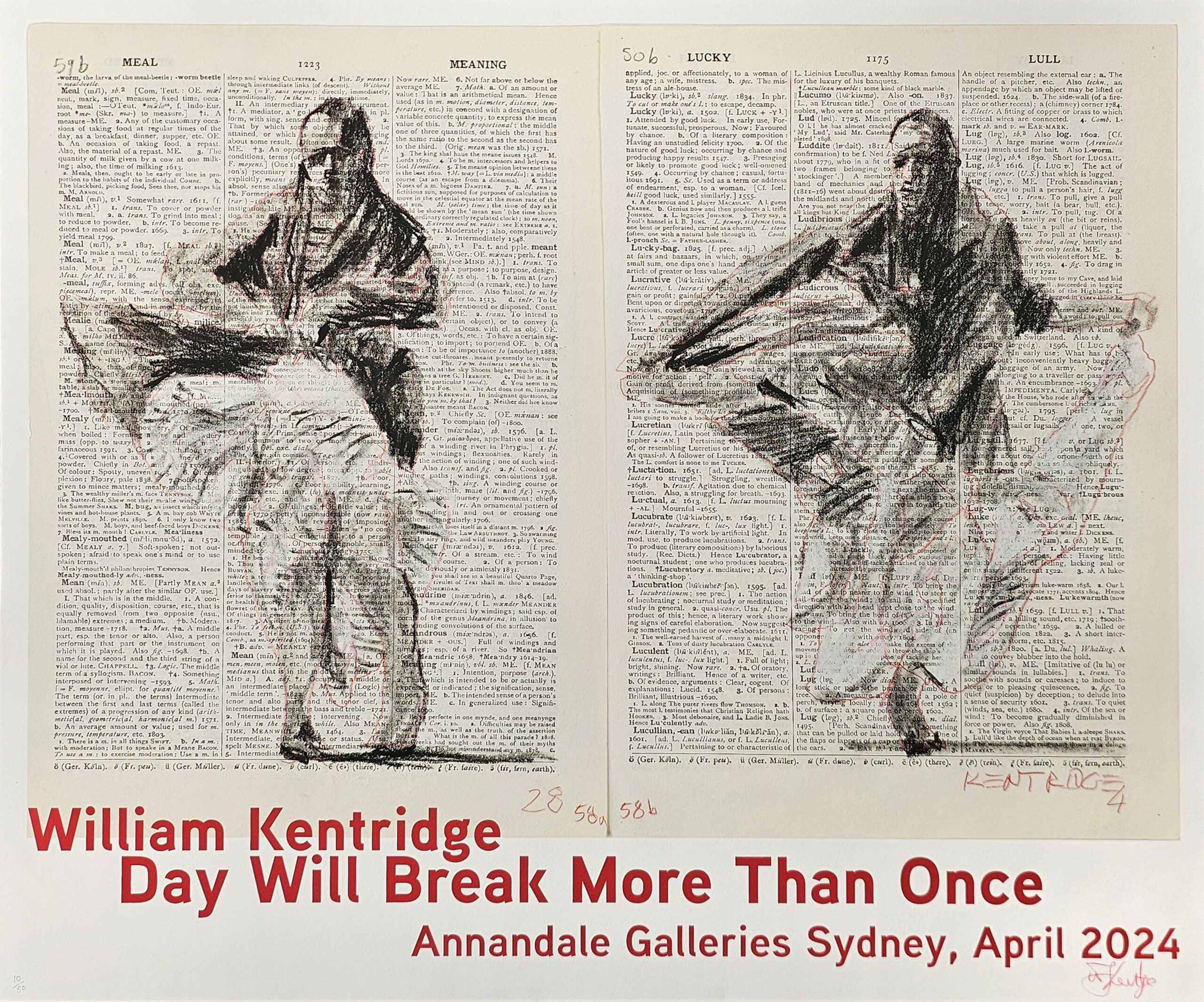

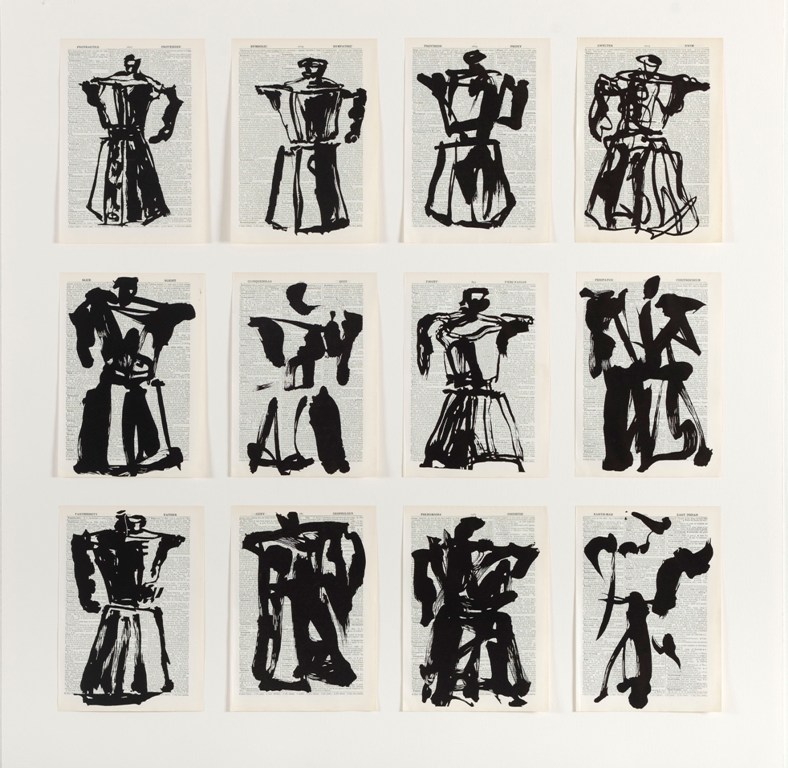

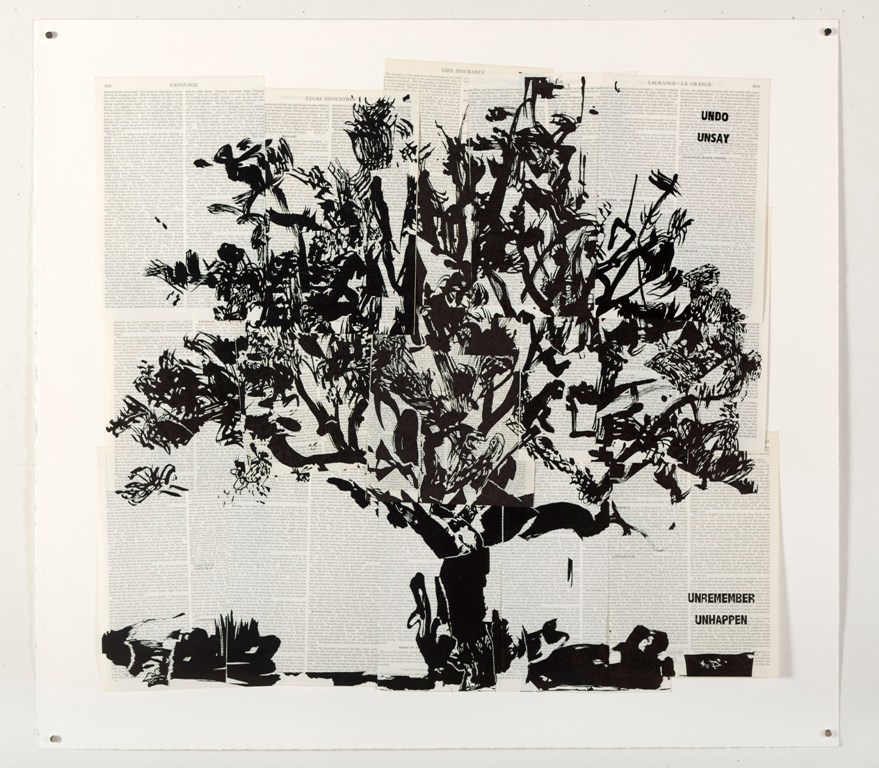

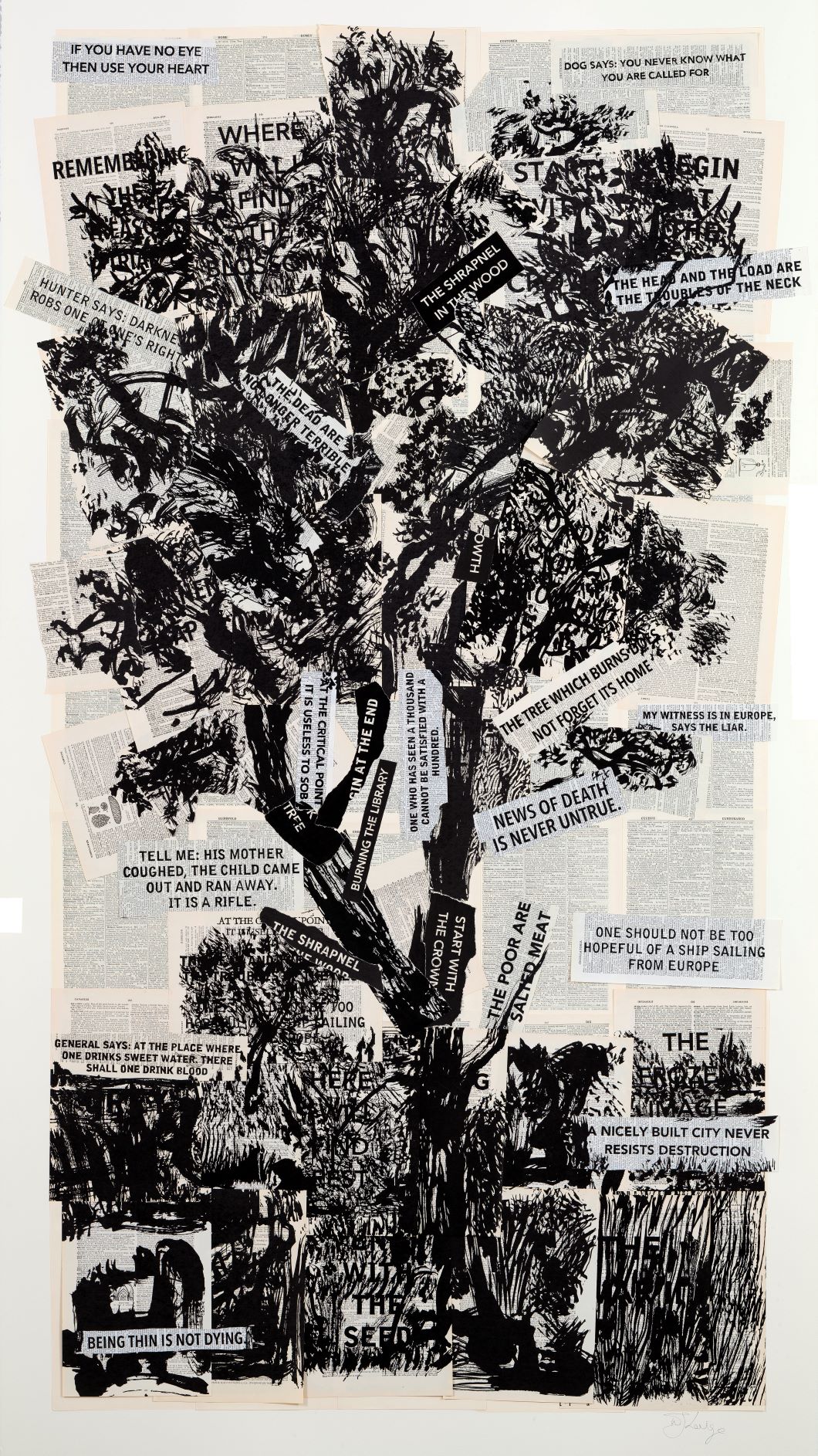

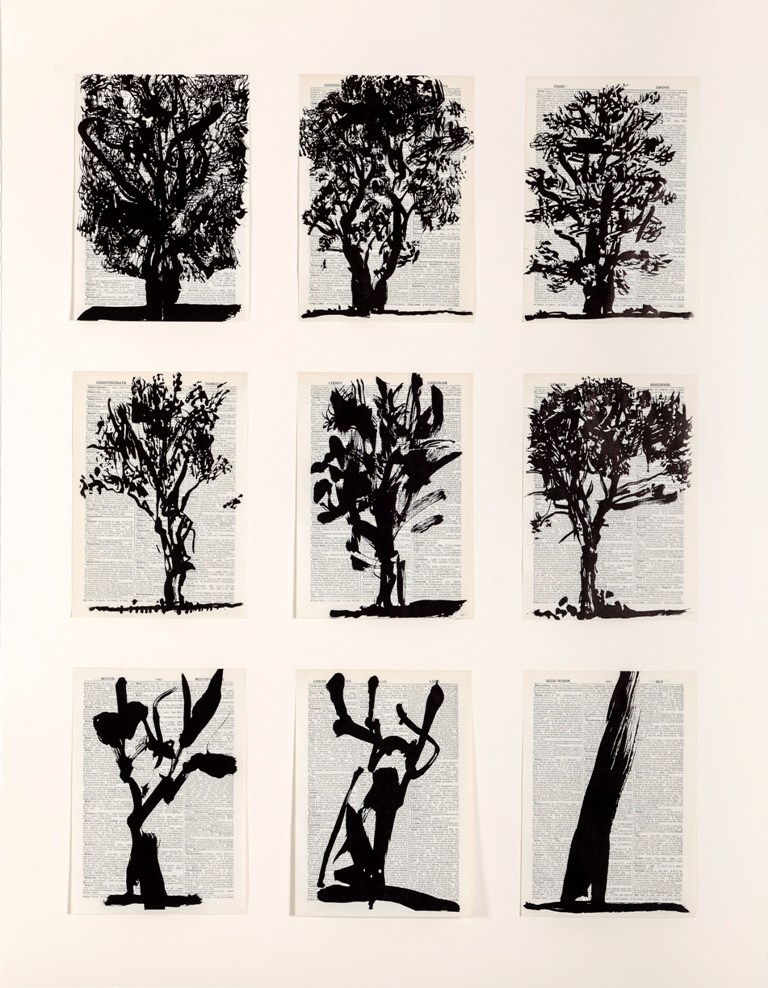

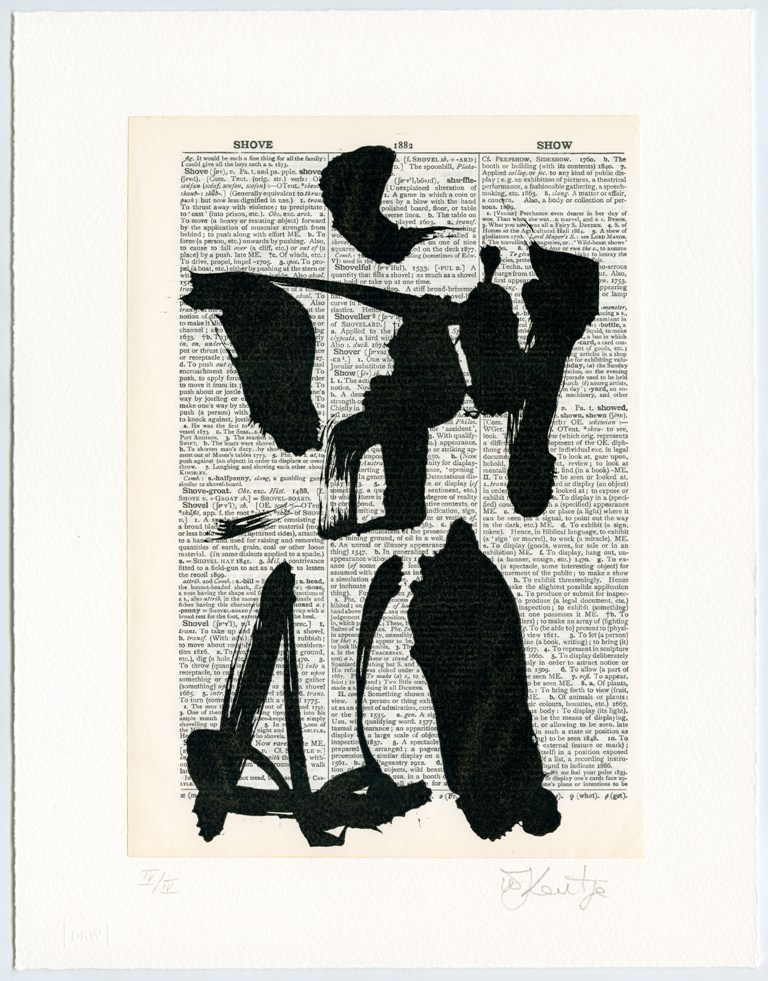

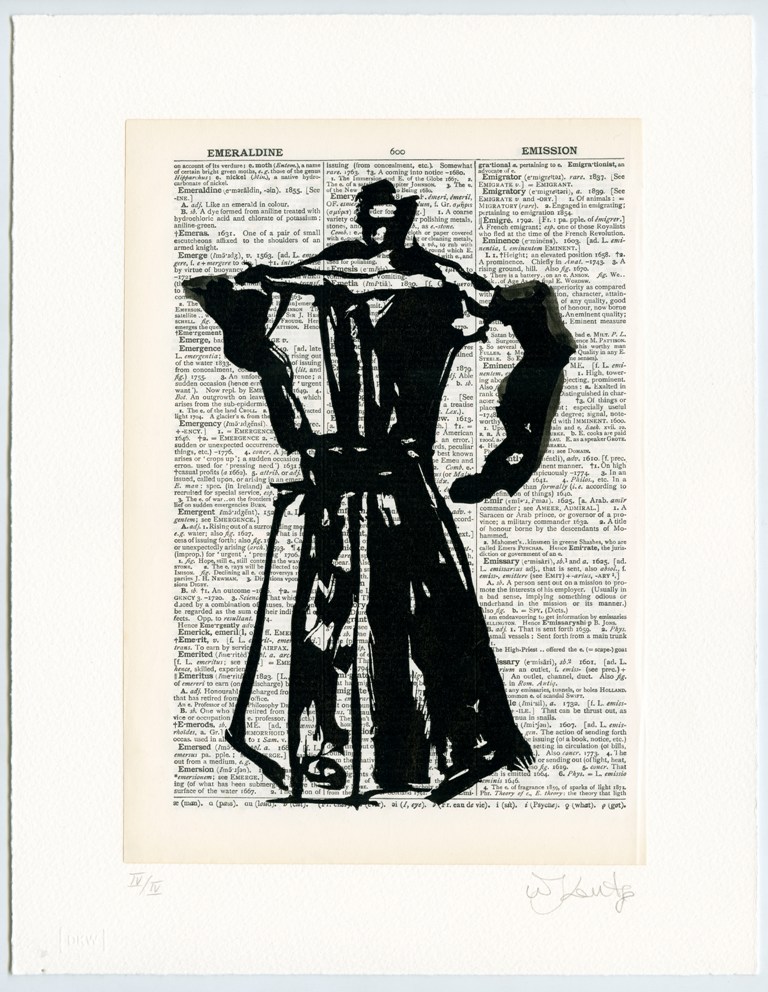

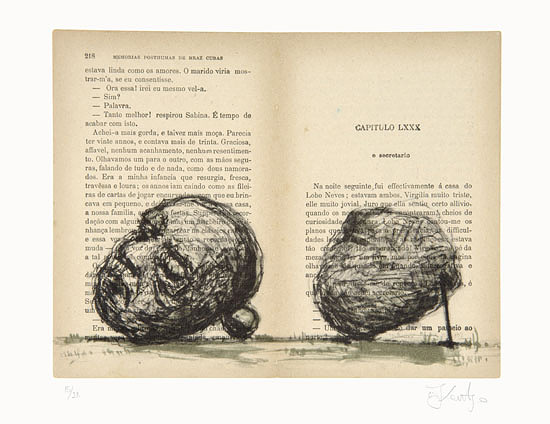

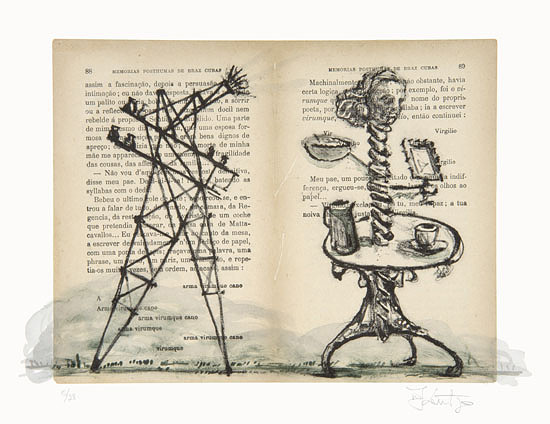

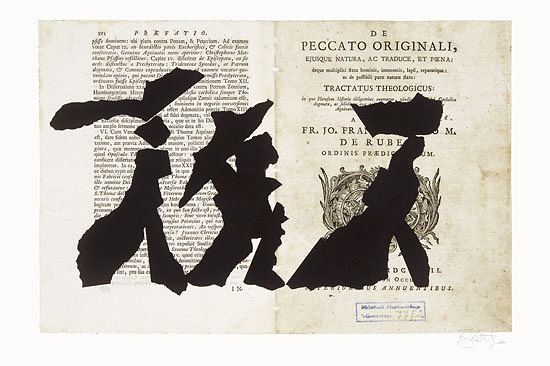

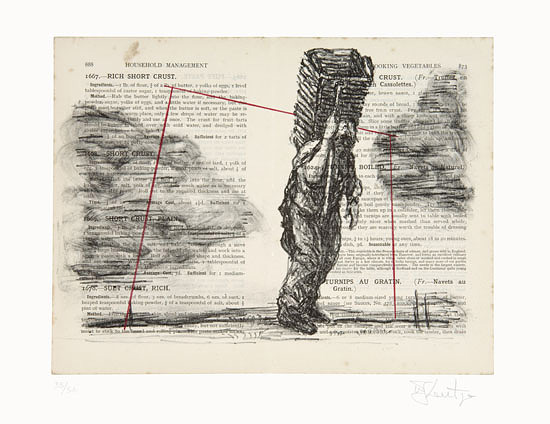

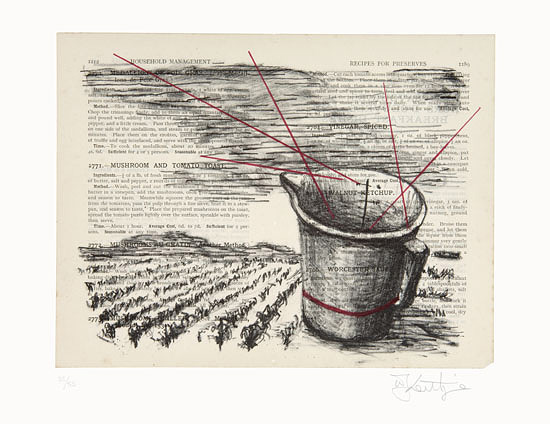

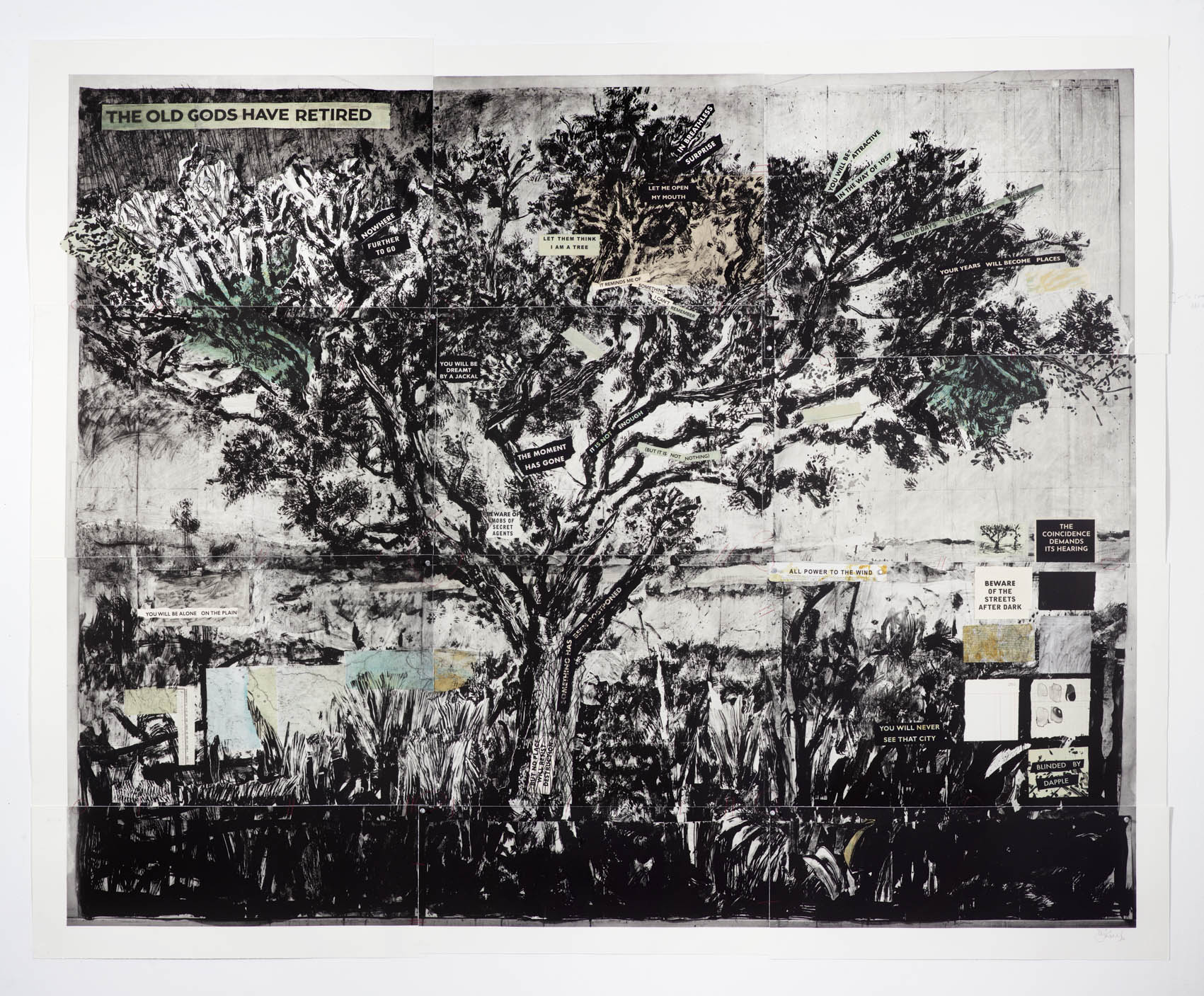

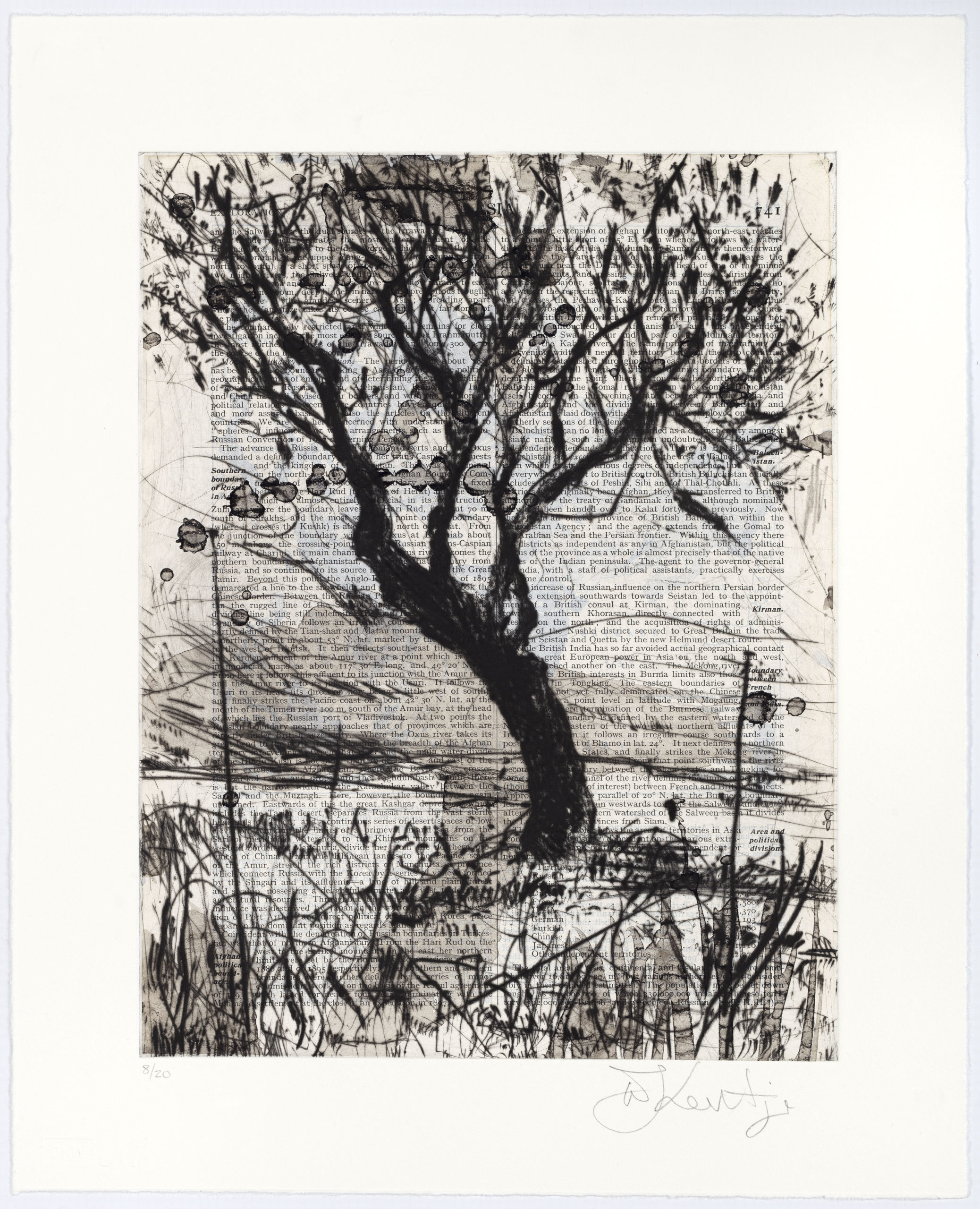

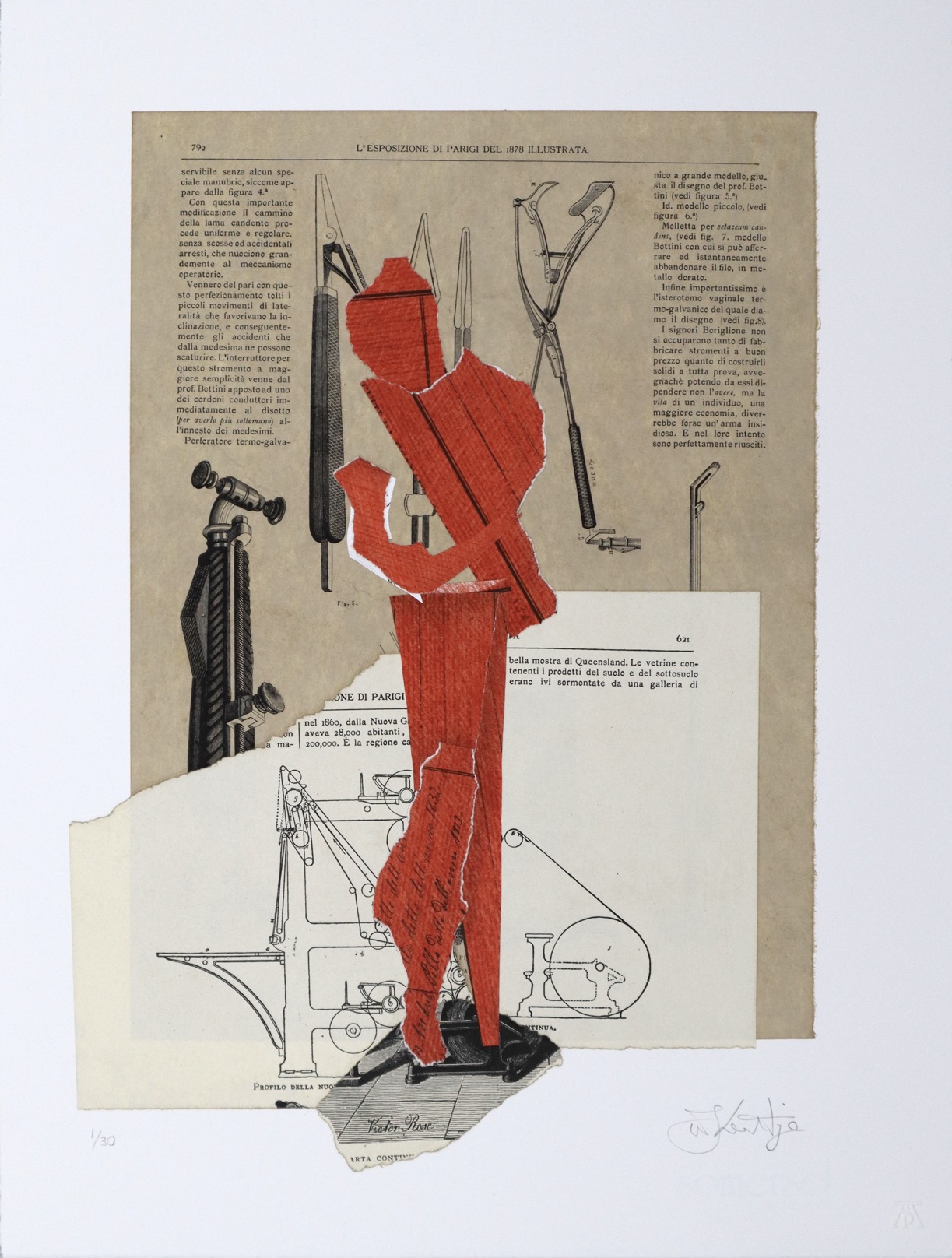

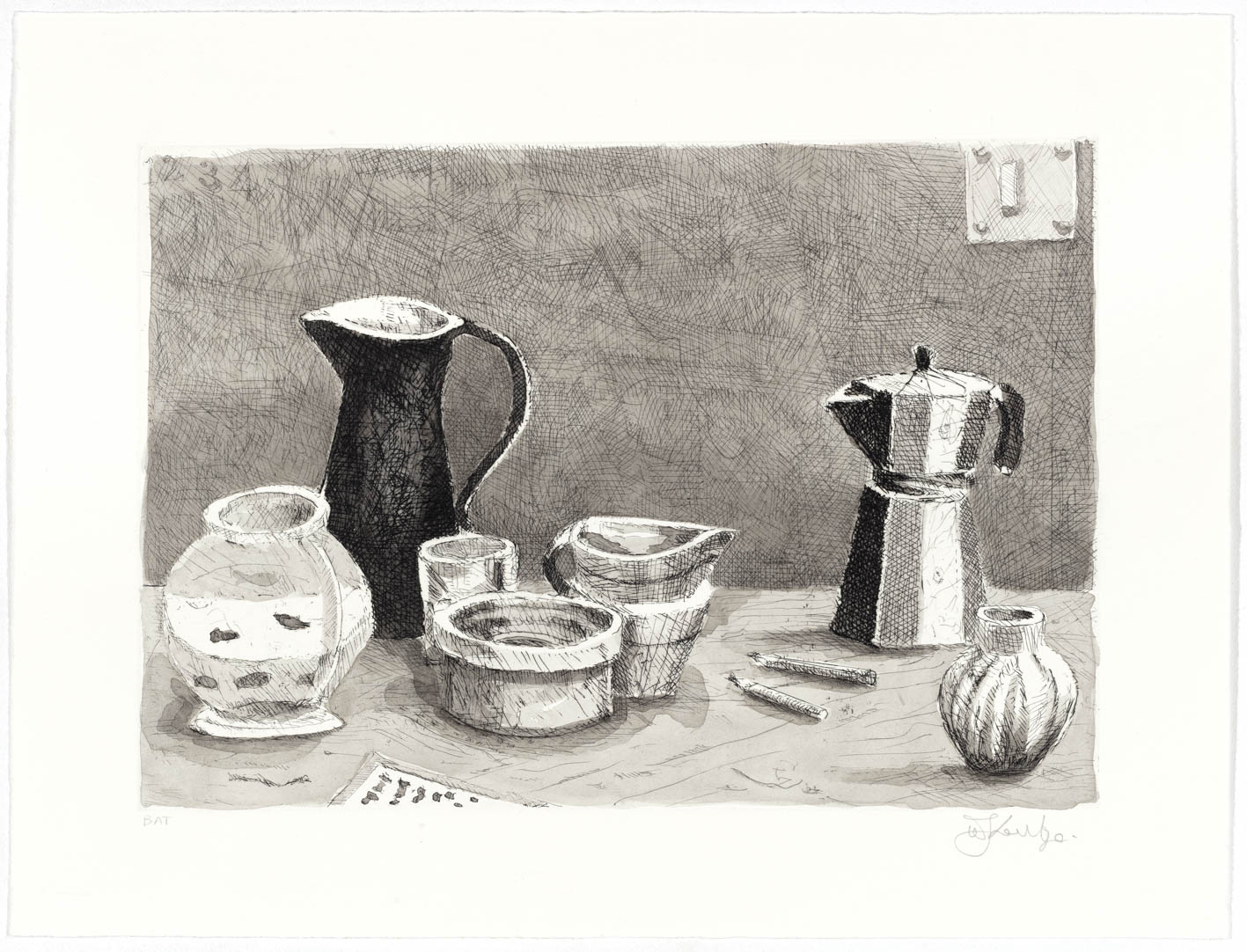

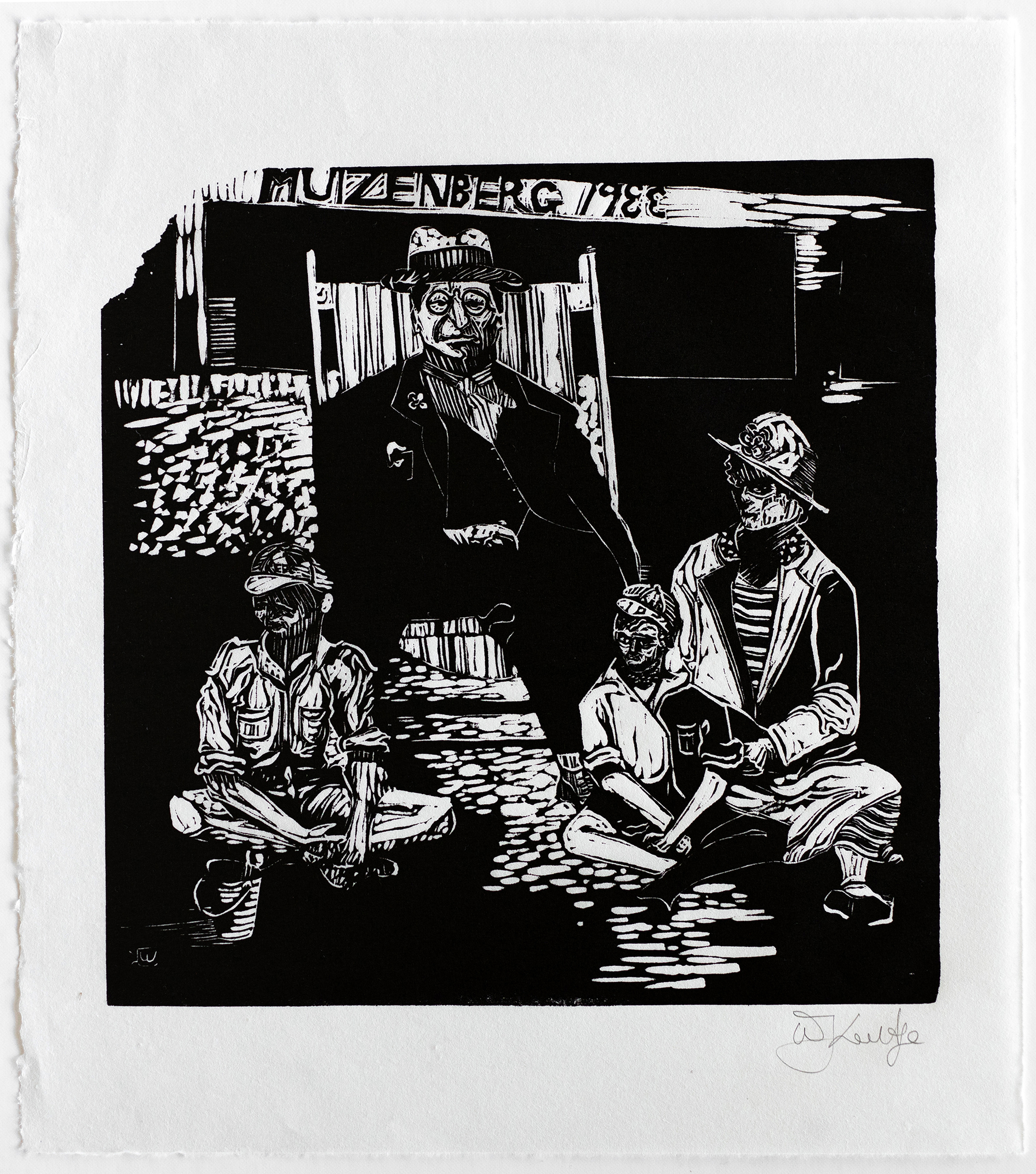

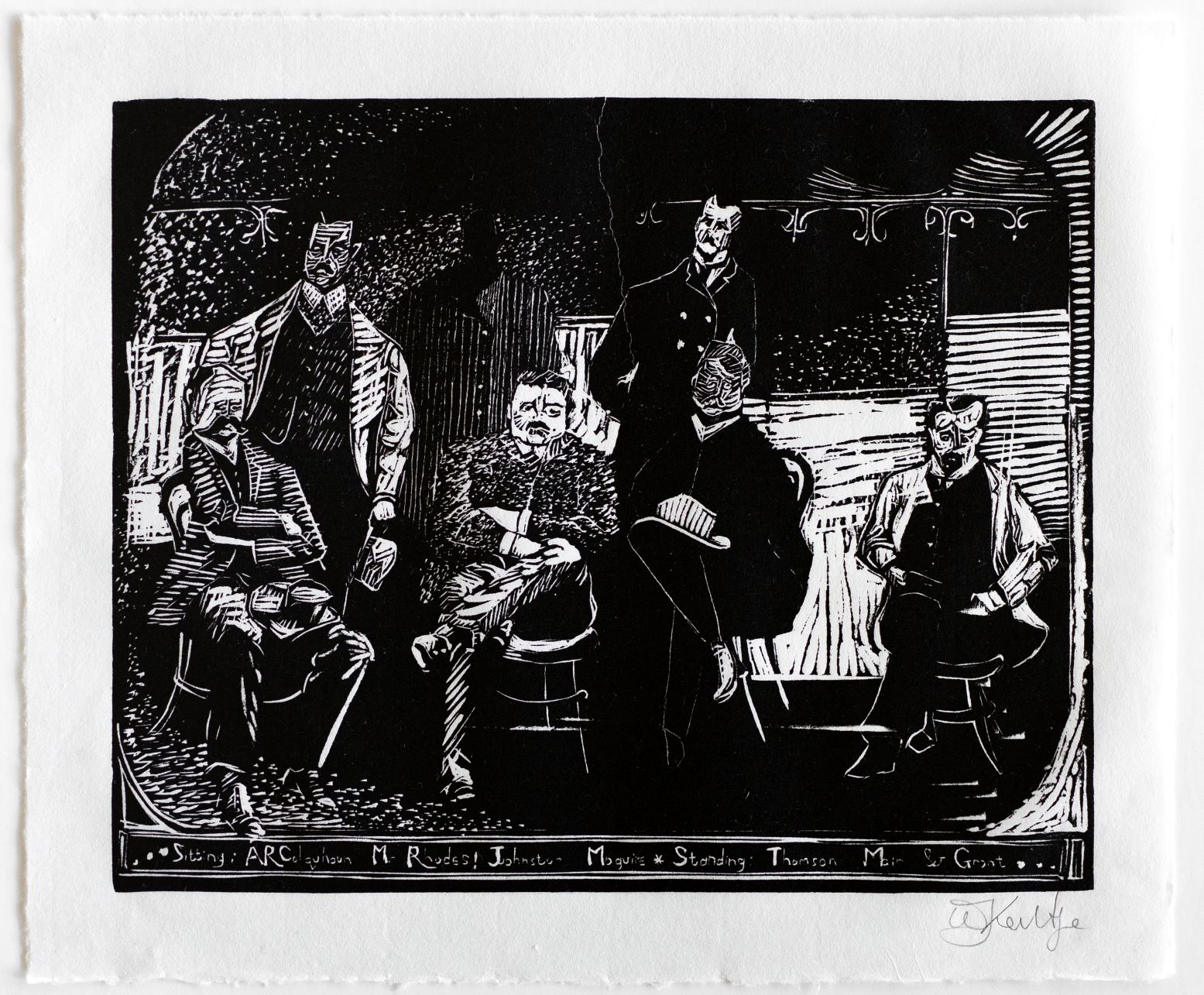

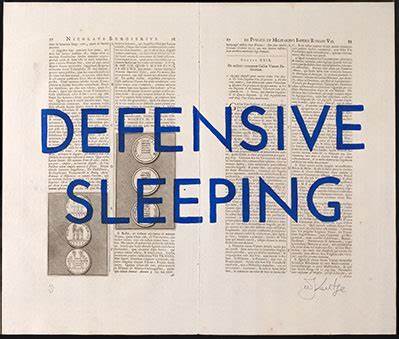

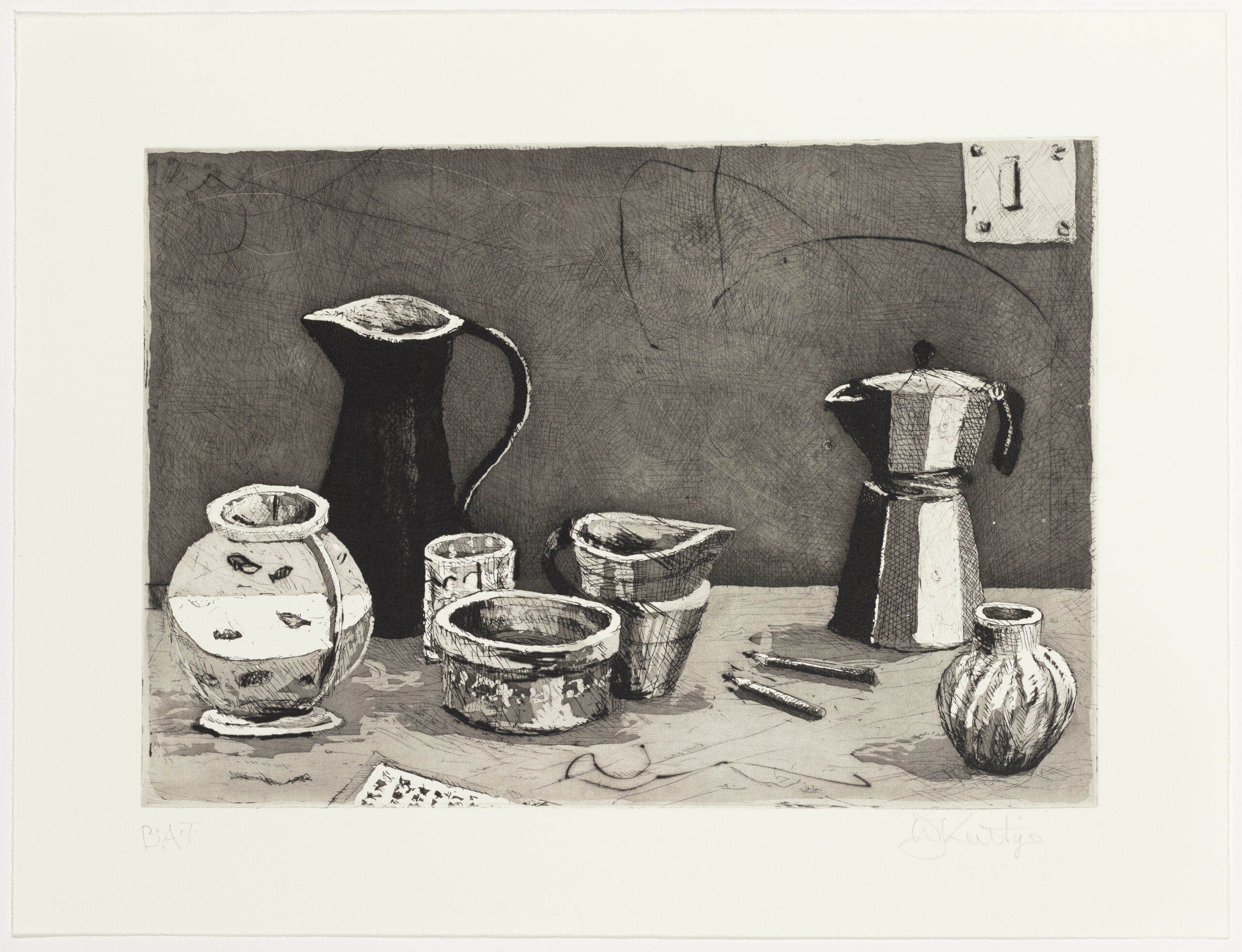

The Universal Archive began at the David Krut Workshop in 2012 and is made up of linocuts printed onto non-archival 1950s dictionary and encyclopaedia paper. The series contains over 70 individual images. Many of which represent recurring motifs commonly seen in Kentridge’s art, ink drawings, sculptures and stage productions. They depict everyday images, such as coffee pots, trees, cats, female nudes, typewriters, horses and birds.

Read more ▼The Universal Archive linocuts began as a series of small Indian ink drawings, created in a state of what Kentridge refers to as “productive procrastination” during the time that he was preparing his Norton series of lectures, presented at Harvard University in 2012. The drawings were made on pages of old dictionaries, using both old and new paintbrushes. The former refers to the pristine new brush, which gives perfectly intentional lines. The latter has damaged, splayed bristles which gives a less certain mark. It is the worn, mistreated brush that artists tend to discard but Kentridge embraces for its individual qualities. Hence, the images are made up of both solid and very fine lines, with an unconstrained virtuosity of mark-making. The ink drawings were initially attached to linoleum plates and painstakingly carved by the DKW printmakers and the artist’s studio assistants. Master Printer Jillian Ross speaks of the exacting process as “a giant puzzle constantly solving”. As the project expanded, the images were photo-transferred to linoleum plates in order to preserve the original drawings. The images have been printed onto pages from various books, including dated copies of the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary and Encyclopaedia Britannica.

The use of dictionary pages for this project is both unusual – considering the paper’s non-archival qualities – and significant – in terms of the manifold associations that spring up within each work as a result of the spontaneous overlap of image and text. The philosophical implications of this choice have been expounded superbly by Kentridge, in a publication produced in collaboration with Jane Taylor:

“A dictionary is not the same size as a head, although it is quite close, and the thousands of pages in the dictionary do not even begin to match the uncountable number of thoughts, associations, flashes of ideas that zoom around inside the head. But nonetheless there is something of the weight and pages enclosed within the covers of a dictionary that has an association with the memories, the thoughts, the knowledge of different kinds, that we have inside our heads. And the drawings on the different pages of the book do not try to give a map of the way they think, but rather put a marker for the processes, unpredictability and marvels of association that we produce in our heads all the time.”

As a result of the meticulous mechanical translation of a gestural mark, the linocuts redefine the characteristics traditionally achieved by the medium. The identical replication of the artist’s free brush mark in the medium of linocut makes for unexpected nuance in mark, in contrast with the heavier mark usually associated with this printing method. Furthermore, the paper of the nonarchival old book pages resists the ink, which creates an appealing glossy glow on the surface of the paper.

Many of the images are recurring themes in Kentridge’s art and stage productions: cats, trees, coffee pots, nude figures. While some images are obvious, others dissolve into abstracted forms suggestive of Japanese Sumi-e painting. Image mis/identification is core to Kentridge’s practice and is richly explored in this series. The parallel and displaced relationships that emerge between the image and the text on the pages relate to Kentridge’s inherent mistrust of certainty in creative processes. This becomes part of a project of unraveling master texts, here questioning ideas of knowledge production and the construction of meaning. Aside from the numerous individual images created, there are prints assembled from pieces: cats torn from four sheets, a large tree created from 15 sheets. Groups of prints featuring combinations of individual images – twelve coffee pots, six birds and nine trees – show the artist’s progressive deconstruction of figurative images into abstract collections of lines, which nonetheless remain suggestive of the original form. The process by which the viewer projects meaning is sincerely rattled. This movement from figuration to abstraction and back, along with the works’ close relationship to Kentridge’s stage productions, suggests that this body of work holds an intriguing place in Kentridge’s oeuvre on the edge of animation and printmaking.

Ross, who has worked with Kentridge since the early 2000s, stresses that an in-depth understanding of the series requires knowledge of the multiplicity inherent in many of Kentridge’s projects, in which the same imagery recurs in varying forms. “Because he often works on a number of projects at once, his ideas for one project tend to fuel another. Images that you see in Universal Archive overlap considerably across many mediums.” Ross adds that she sees the title as “a reference to his personal ‘universal archive’ – the themes and images that he repeatedly draws on to animate his work.”

Text by Jacqueline Flint, 2020

Loading more artworks...

Archived Editions

This selection lists editioned work by William Kentridge that is no longer available on the primary market.

Loading more artworks...

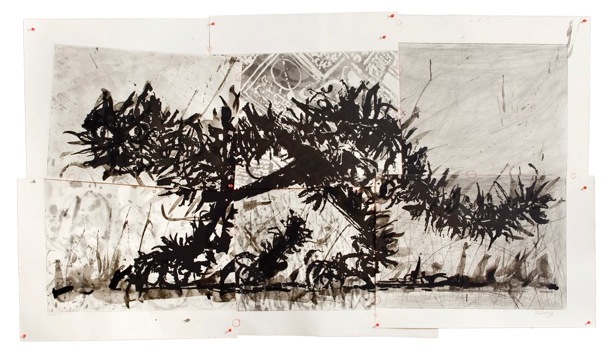

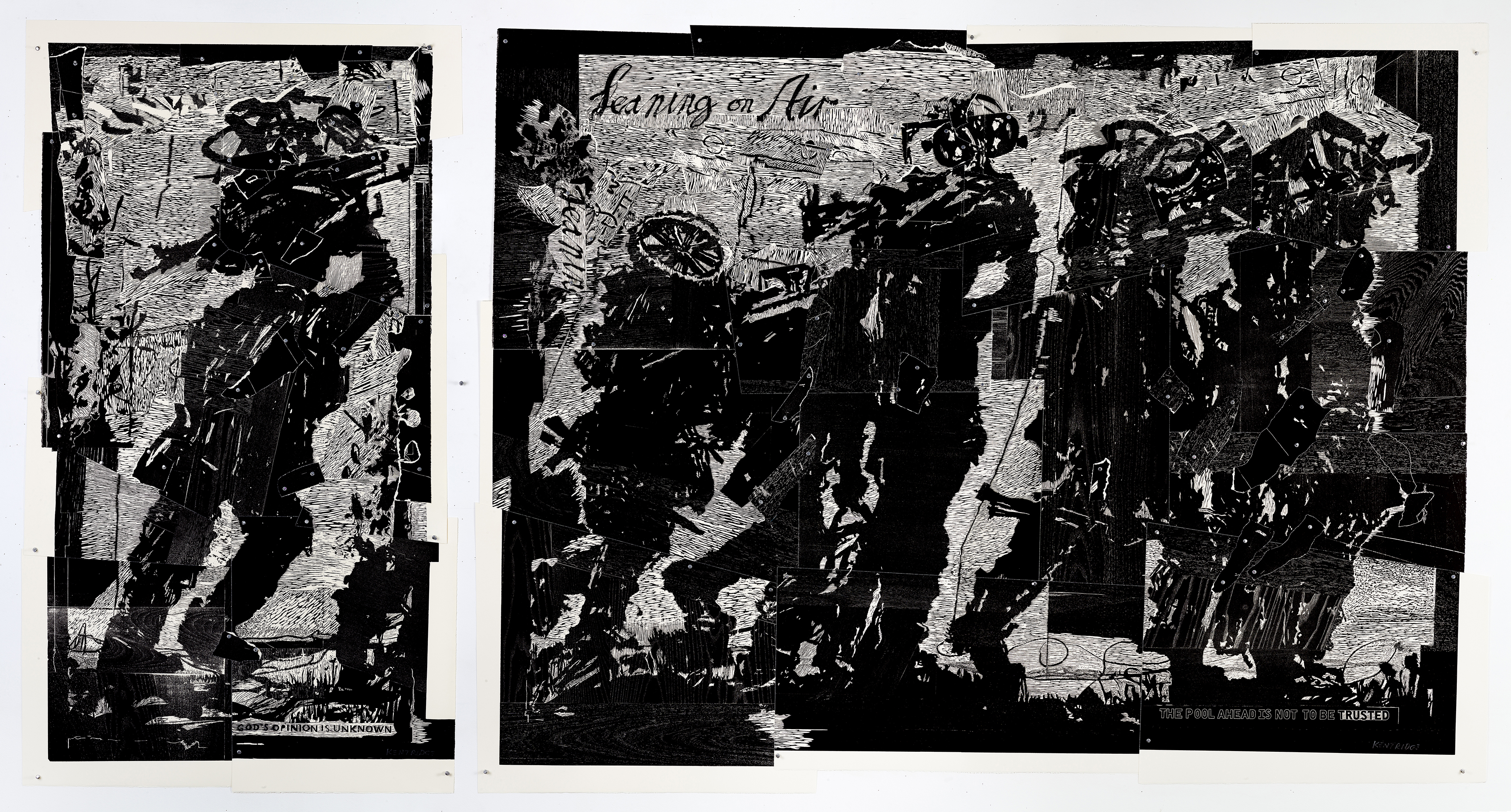

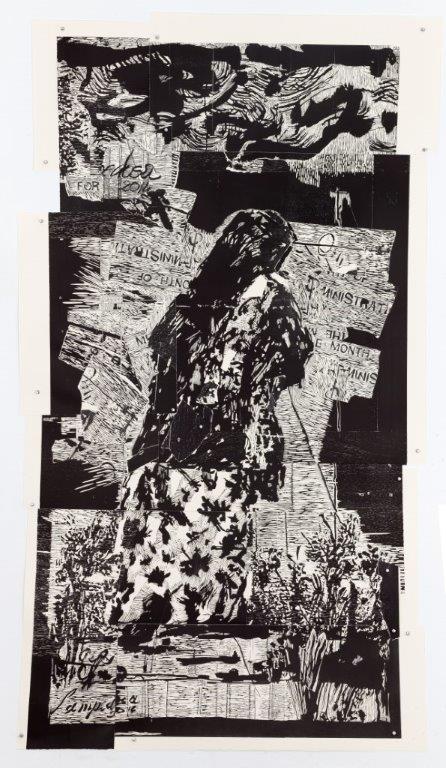

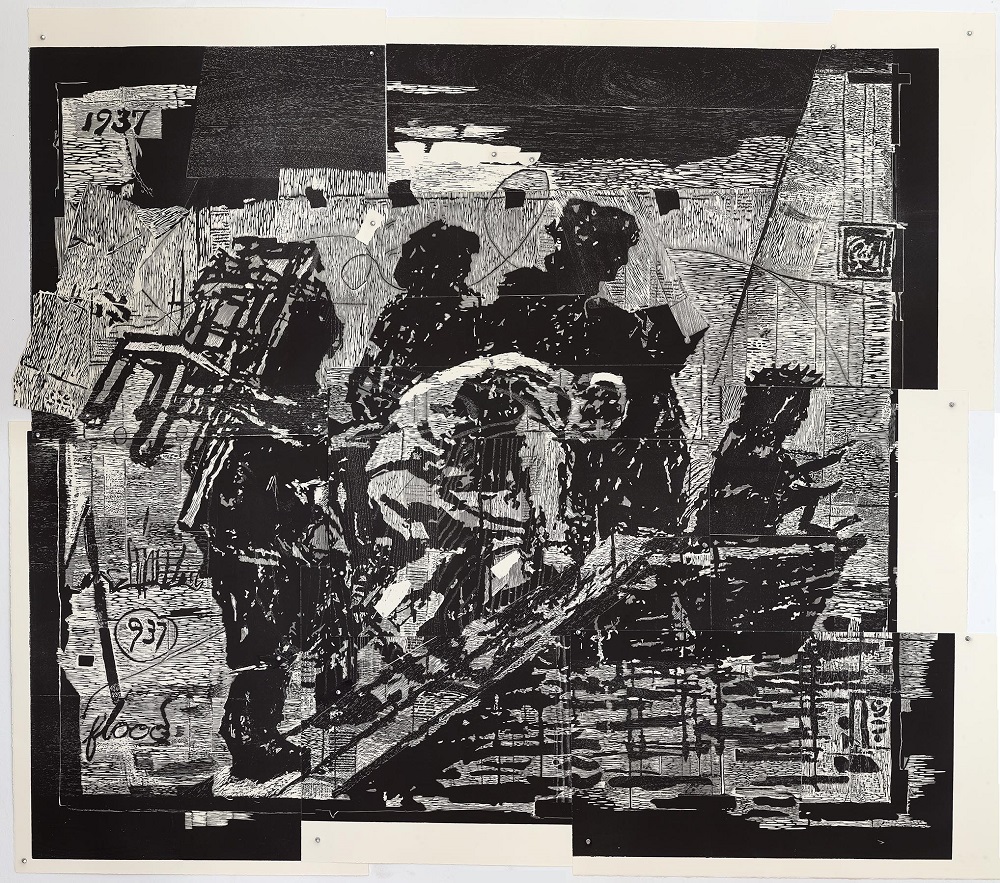

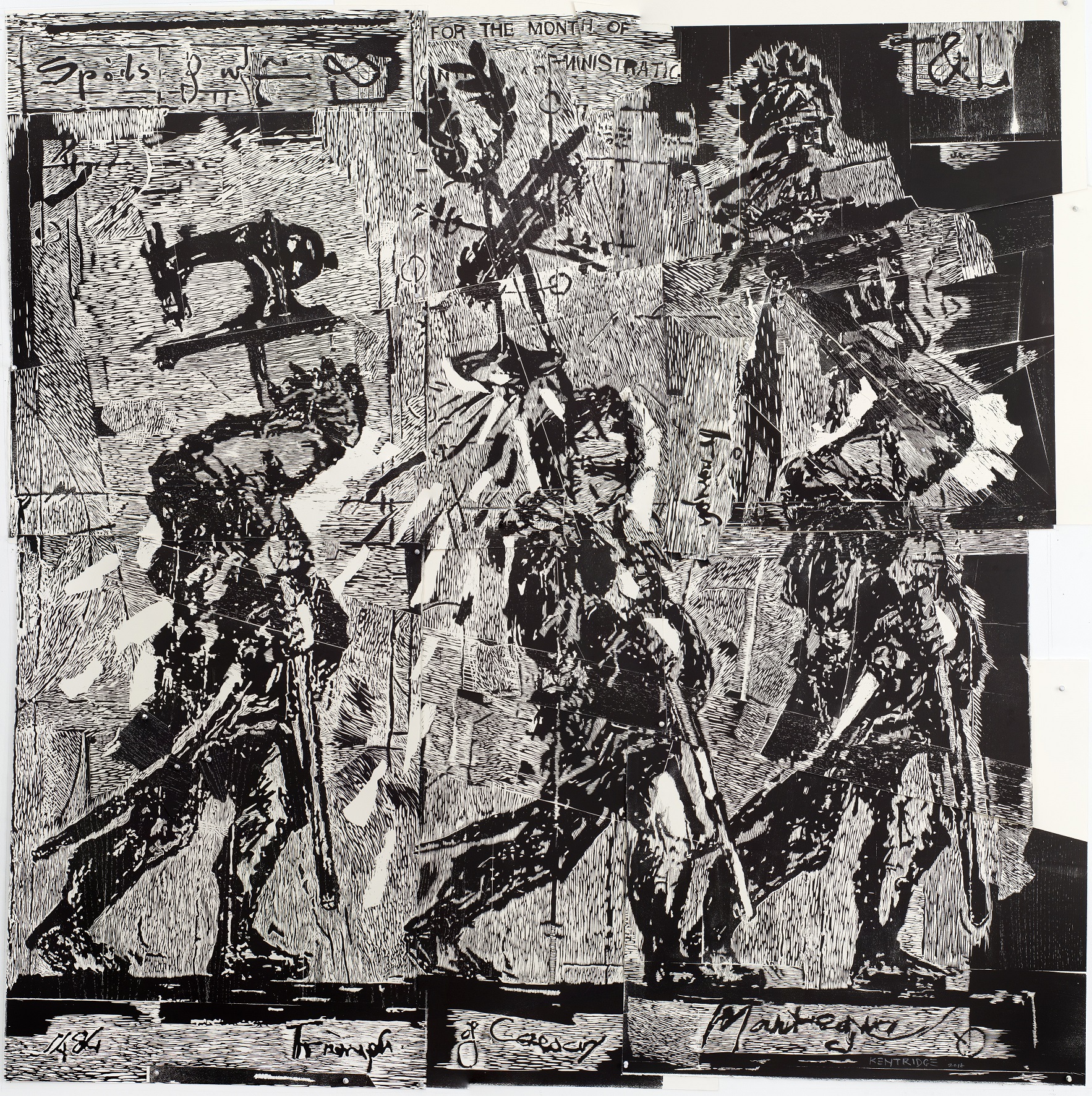

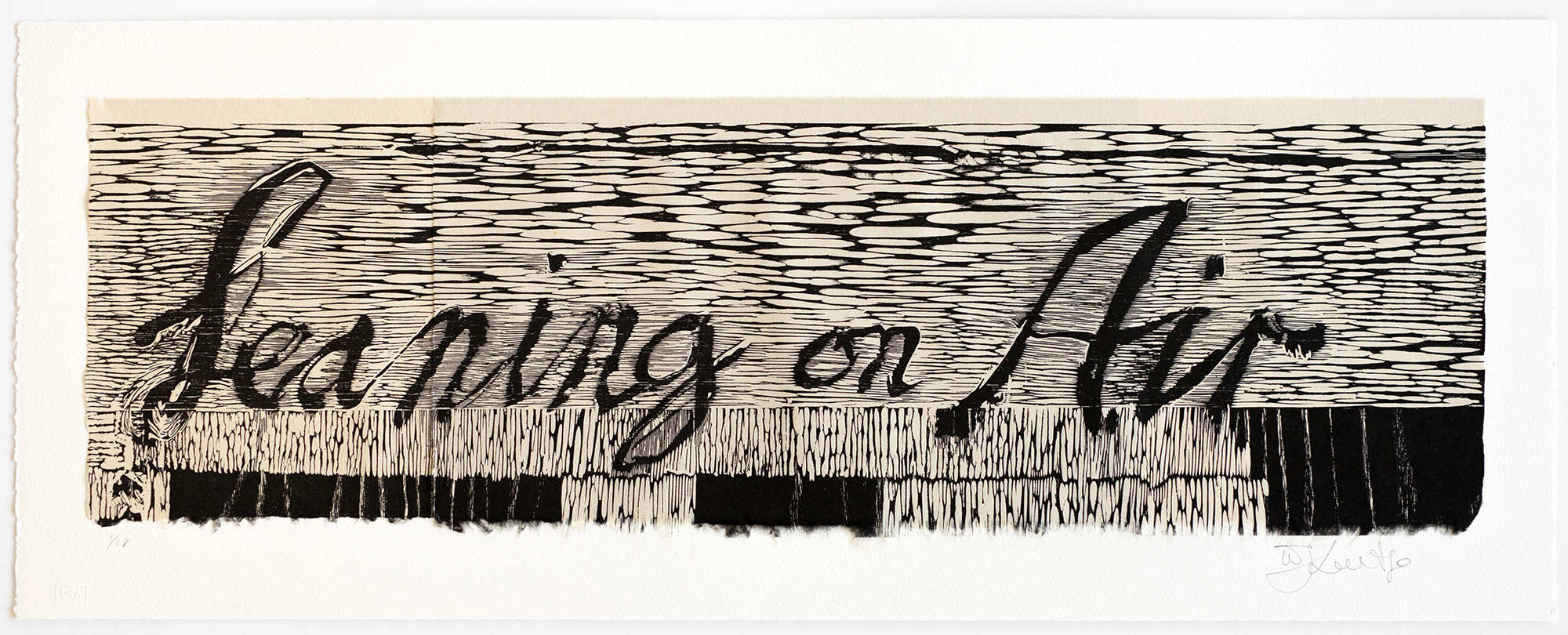

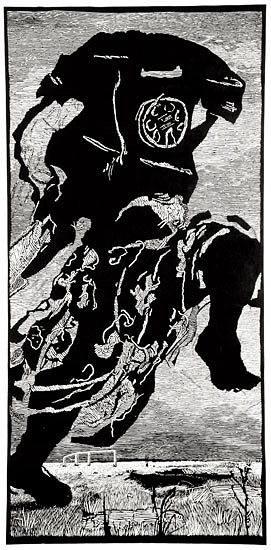

Triumphs and Laments Woodcuts

In 2016, and for some years prior, William Kentridge was at work on a monumental frieze, called Triumphs and Laments: A Project for Rome, to be installed along the banks of the Tiber River. The work was designed to span 550 metres of an embankment of the river on Piazza Tevere: a procession of 55 drawings delving into the history of Rome from ancient times to the present, integrated with references to current world happenings, which open up conversations about the nature of history and how it is recorded; our capacity to remember, and to forget. For each drawing a stencil was created around which the surface of the wall was pressure-cleaned, leaving behind an image drawn in residue grime. As the natural environmental effects of pollution and bacteria amass once again on the wall, the images are erased.

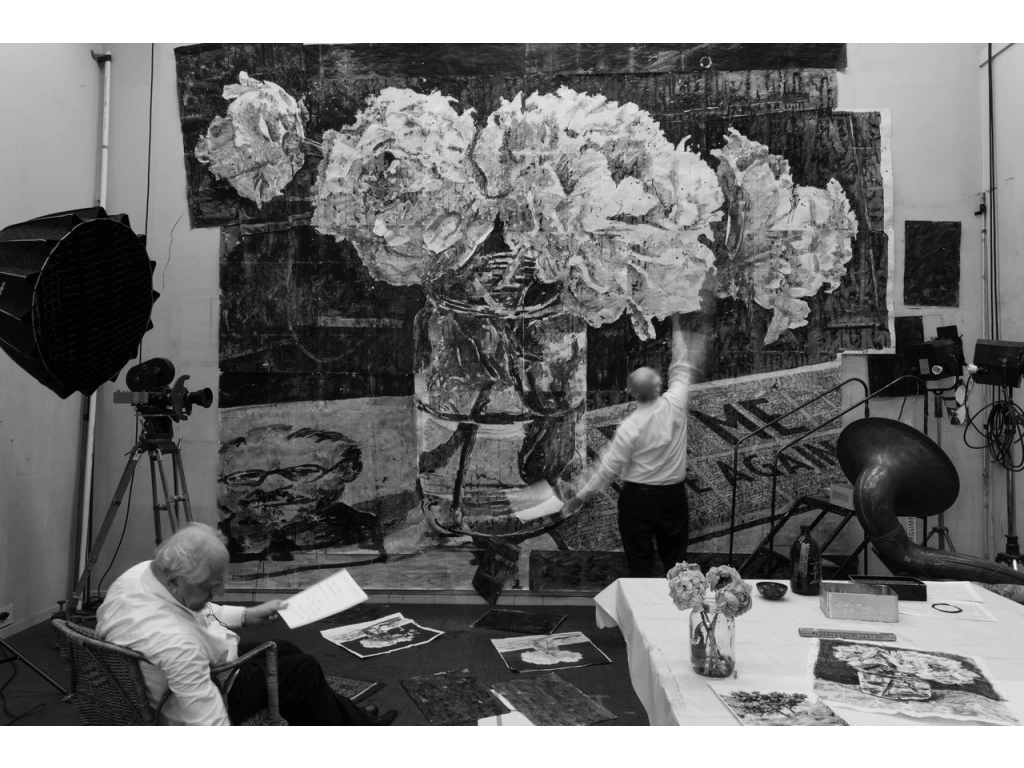

Read more ▼In January 2016 Jillian Ross, Master Printer of Johannesburg’s David Krut Workshop (DKW), was invited to spend an afternoon in Kentridge’s Houghton studio. At the time, preparations for the frieze project were in motion, the walls and surfaces of the studio covered with proposed layouts, scale tests, preliminary drawings and plans. Ross and Kentridge began exploring the idea of using these drawings as the basis for a print collaboration.

A number of different avenues were investigated, and Ross left mulling over a few ideas. For Ross, an important considerations was the ability to build on the skills acquired in previous projects so as to go beyond what had been achieved before.

Considering that the images stencilled onto the Tiber wall are ultimately fugitive, in time all that will remain of the project are the outcomes of collaborations that happened alongside and as a result of it. The Tiber River procession was an extraordinarily ambitious pursuit and the print collaboration needed to do justice to the scale and intent, albeit in a different arena. Woodcut was finally settled upon as the medium – a challenge in itself, having not worked together in the medium before. And so they embarked on a journey that led to the creation of a series of six almost-life-size, multi-sheet, multi-timber woodcut prints, which unfolded over the course of three years.

The Triumphs & Laments Woodcut Series has been shown extensively, as a whole and in parts, over the course of the years in which it was made.

2019 saw two large-scale retrospective exhibitions of Kentridge’s work – in Cape Town, at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (MOCAA) and at the Kunstmuseum Basel – which presented the artist with an opportunity to review a selection of his work spanning the last 40 years. The Triumphs & Laments Woodcut Series was included in both these exhibitions as a pinnacle project for Kentridge in terms of his dedication to print media. The series, and its relationship to the Triumphs & Laments frieze project in Rome, is also an excellent acknowledgement of Kentridge’s dedication to impermanence and contingency in terms of making sense – of politics, of social commentary, of history.

Text by Jacqueline Flint, 2020

Each print comes unassembled with the following contents included:

- a black linen portfolio box that houses

- an instructions manual

- a booklet on the making of each artwork

- the number of prints found in the finished work

- the number of aluminum pins found in the finished work

- two acetate sheets with registration notes (life size)

Collaborations

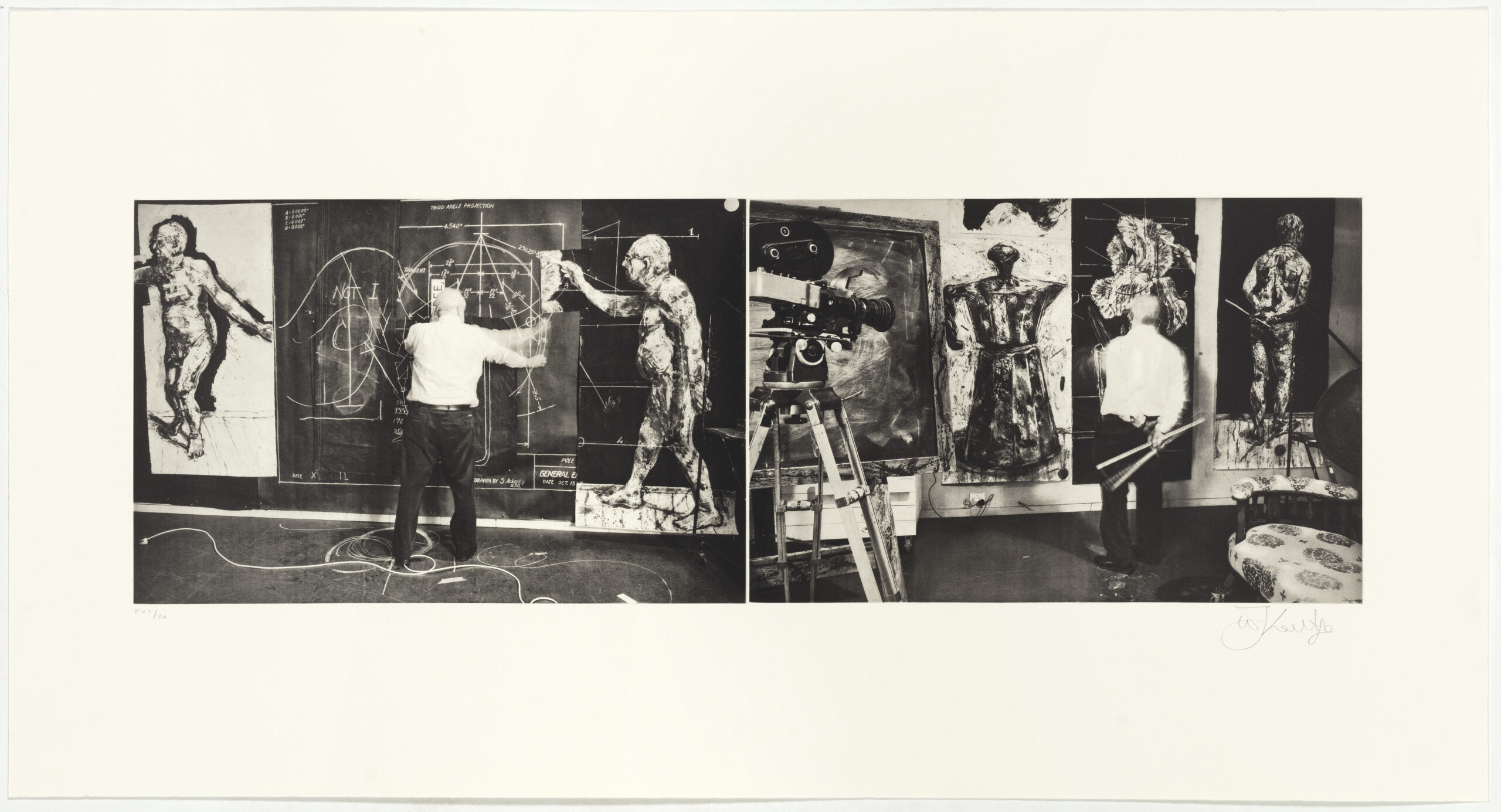

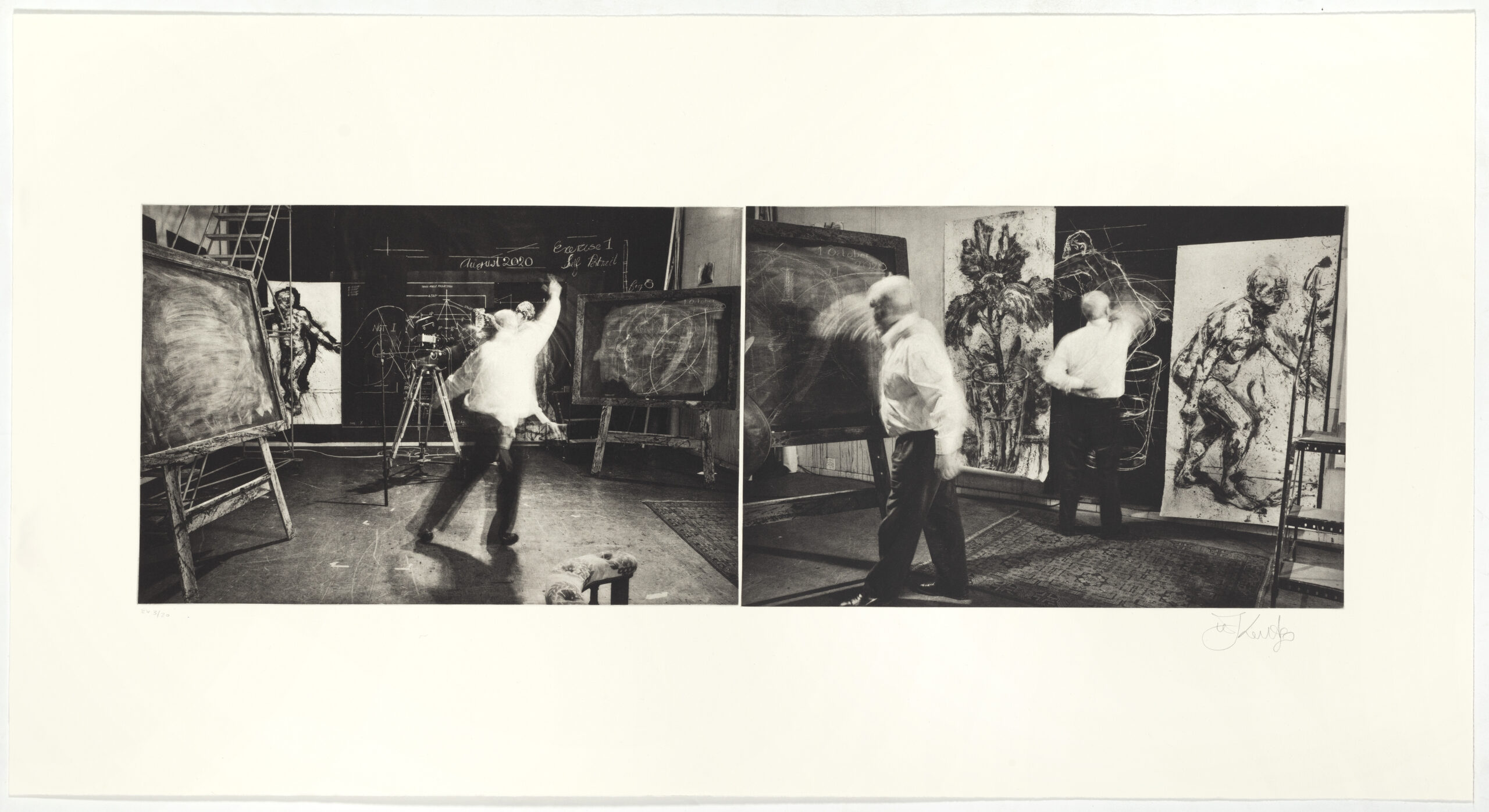

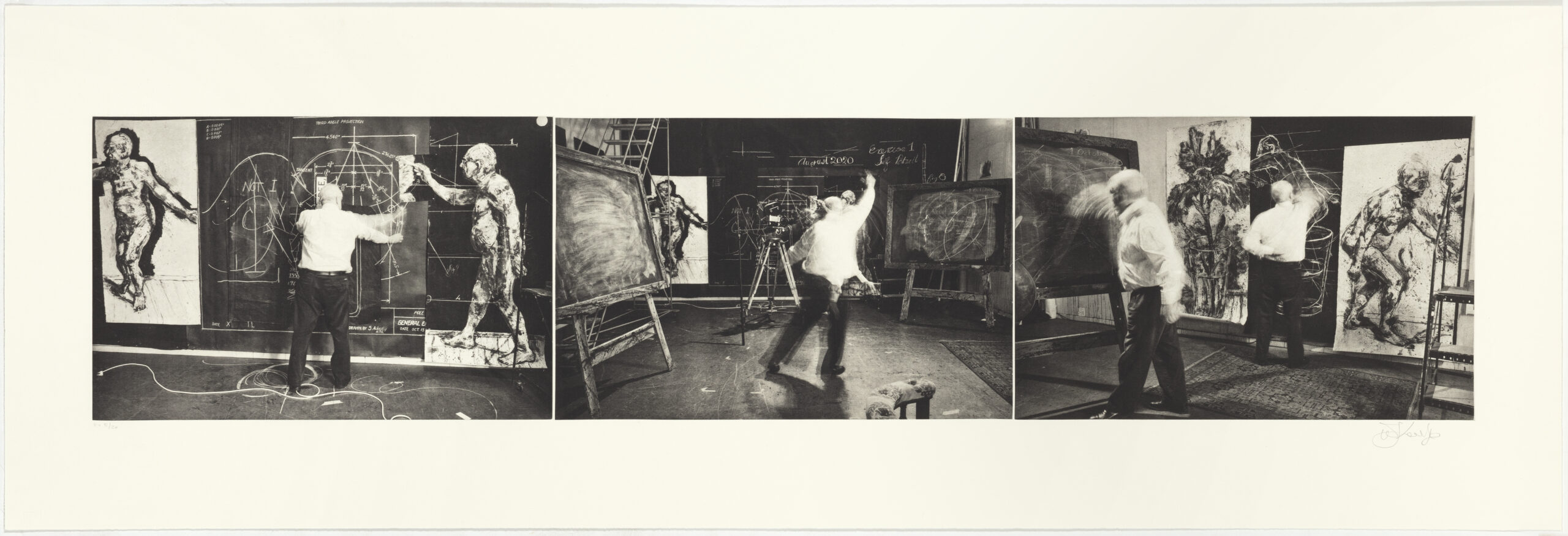

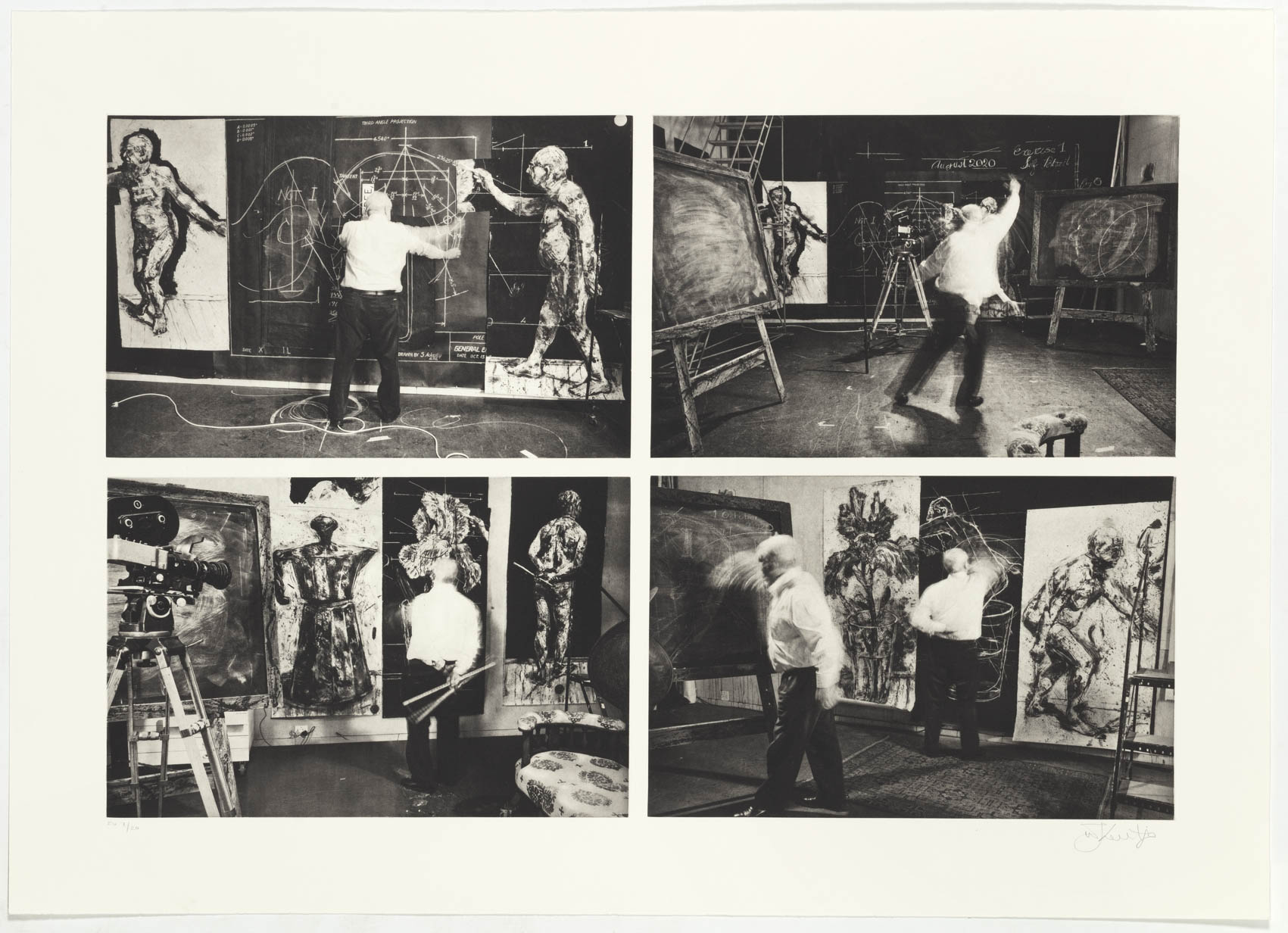

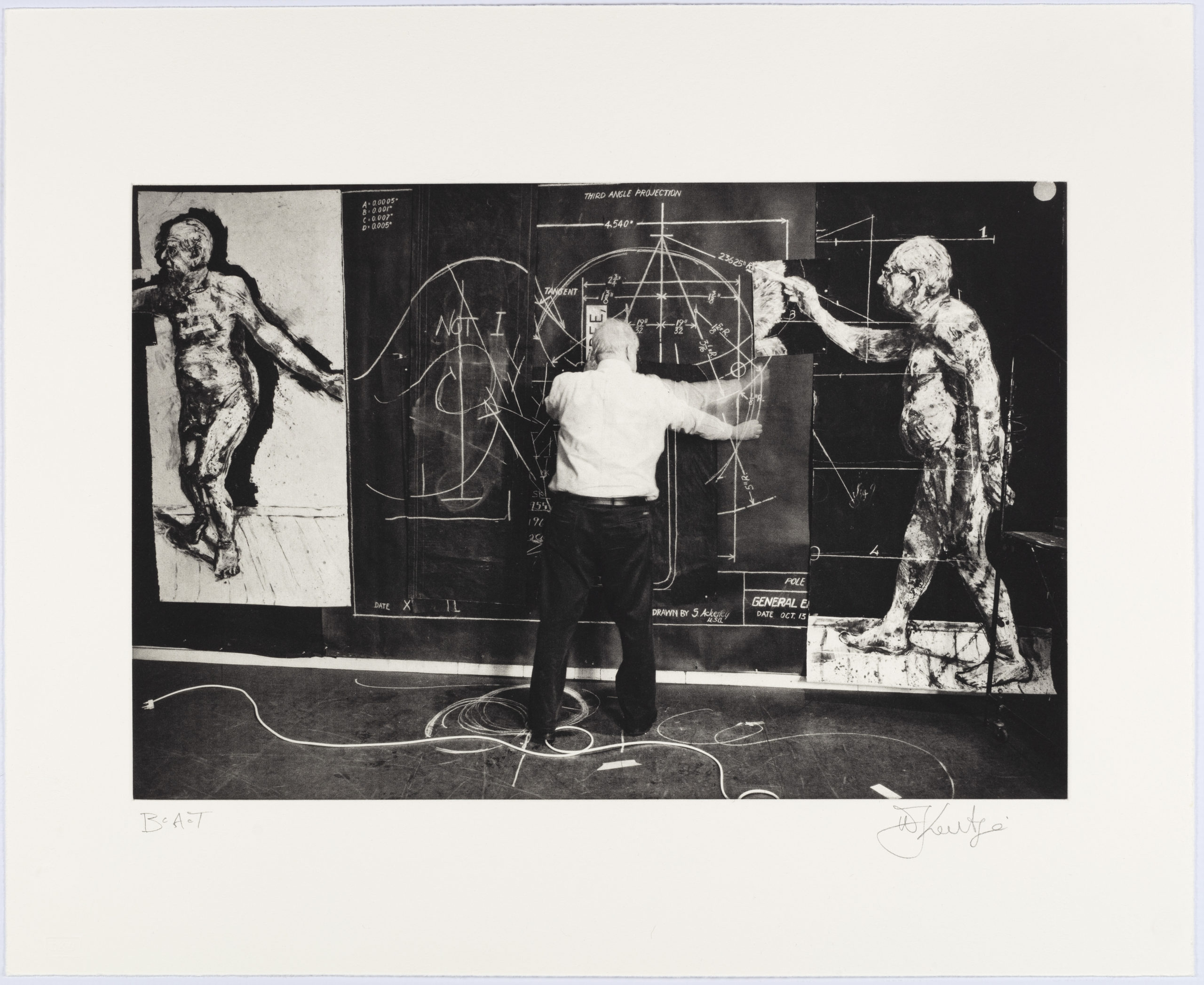

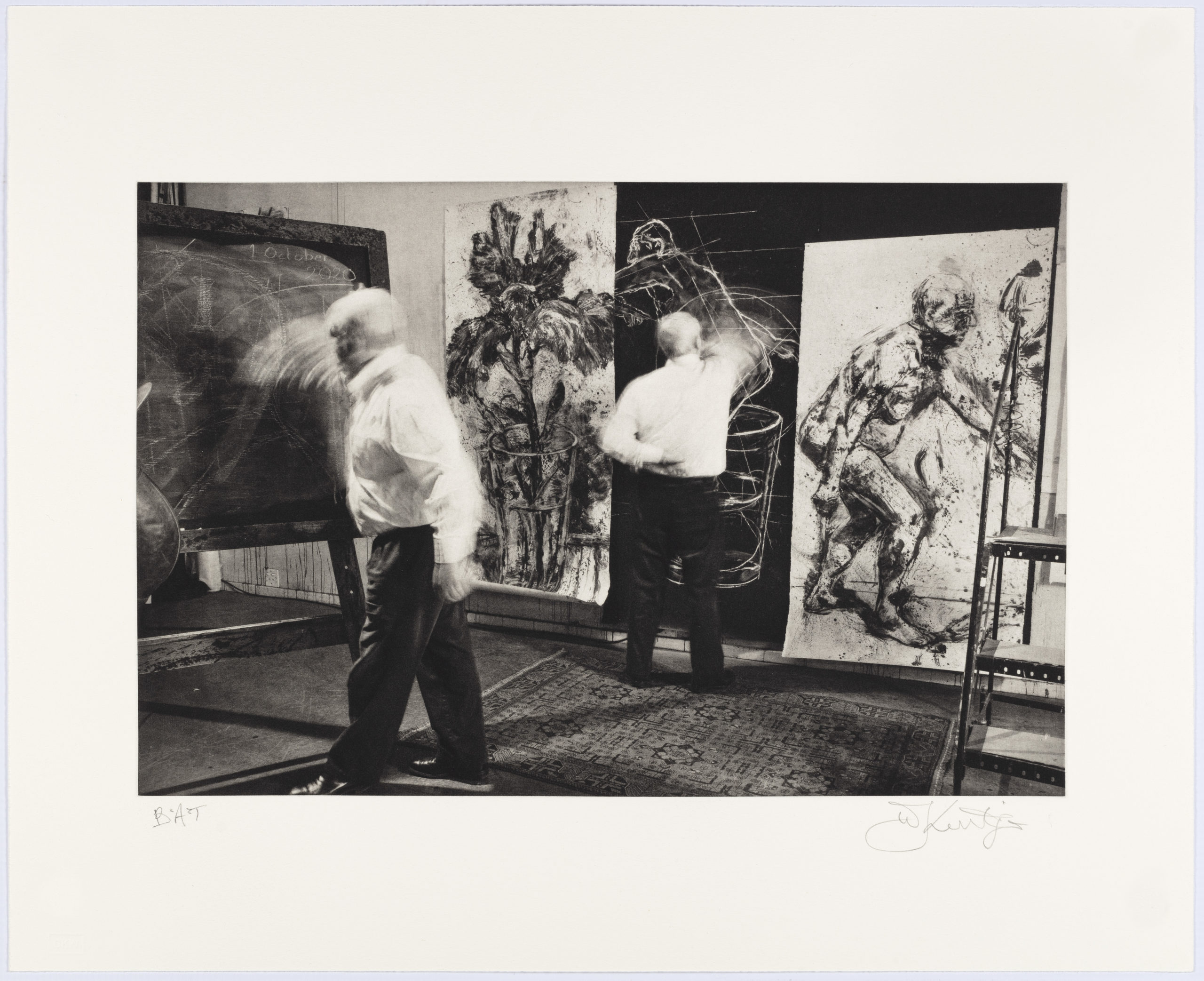

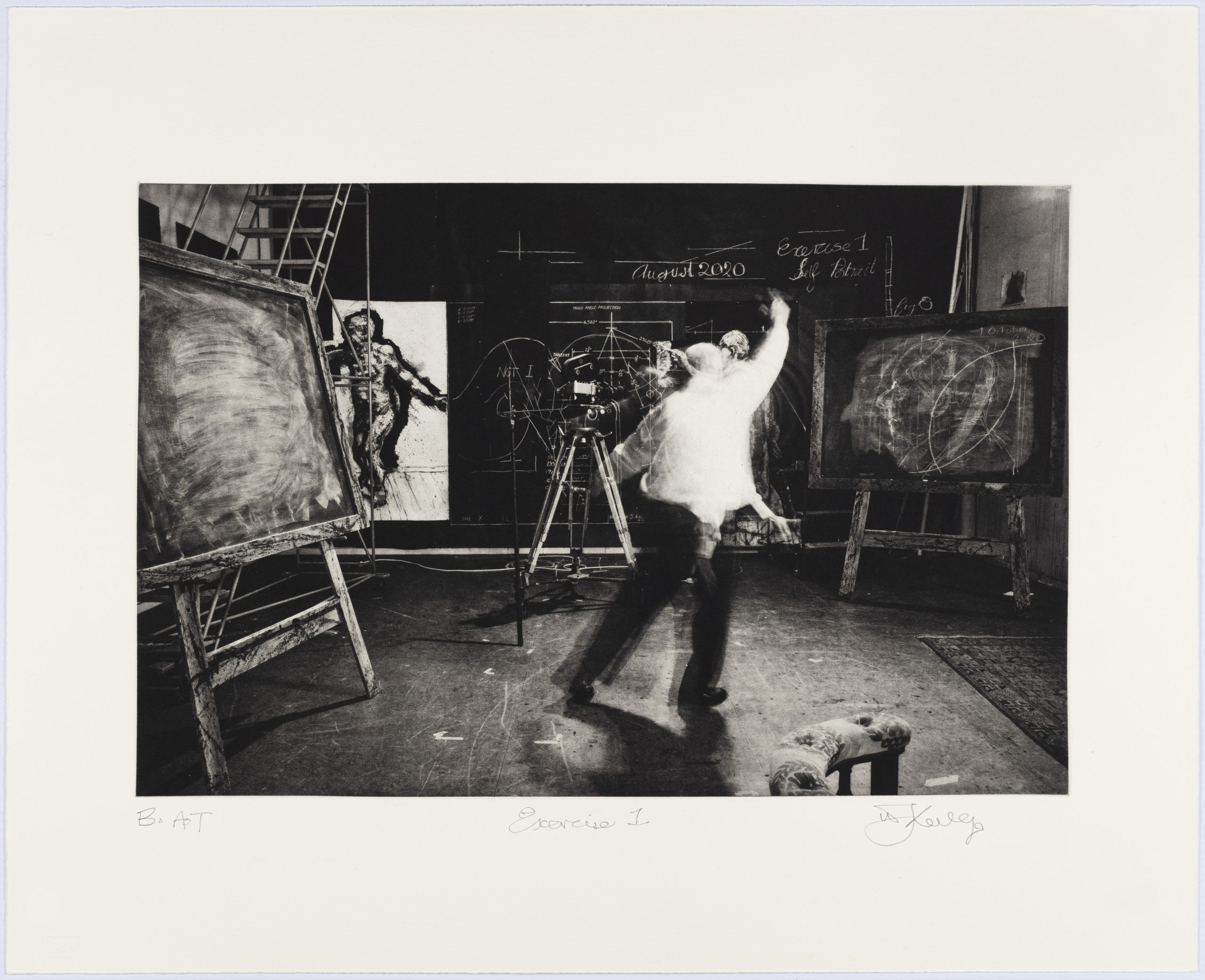

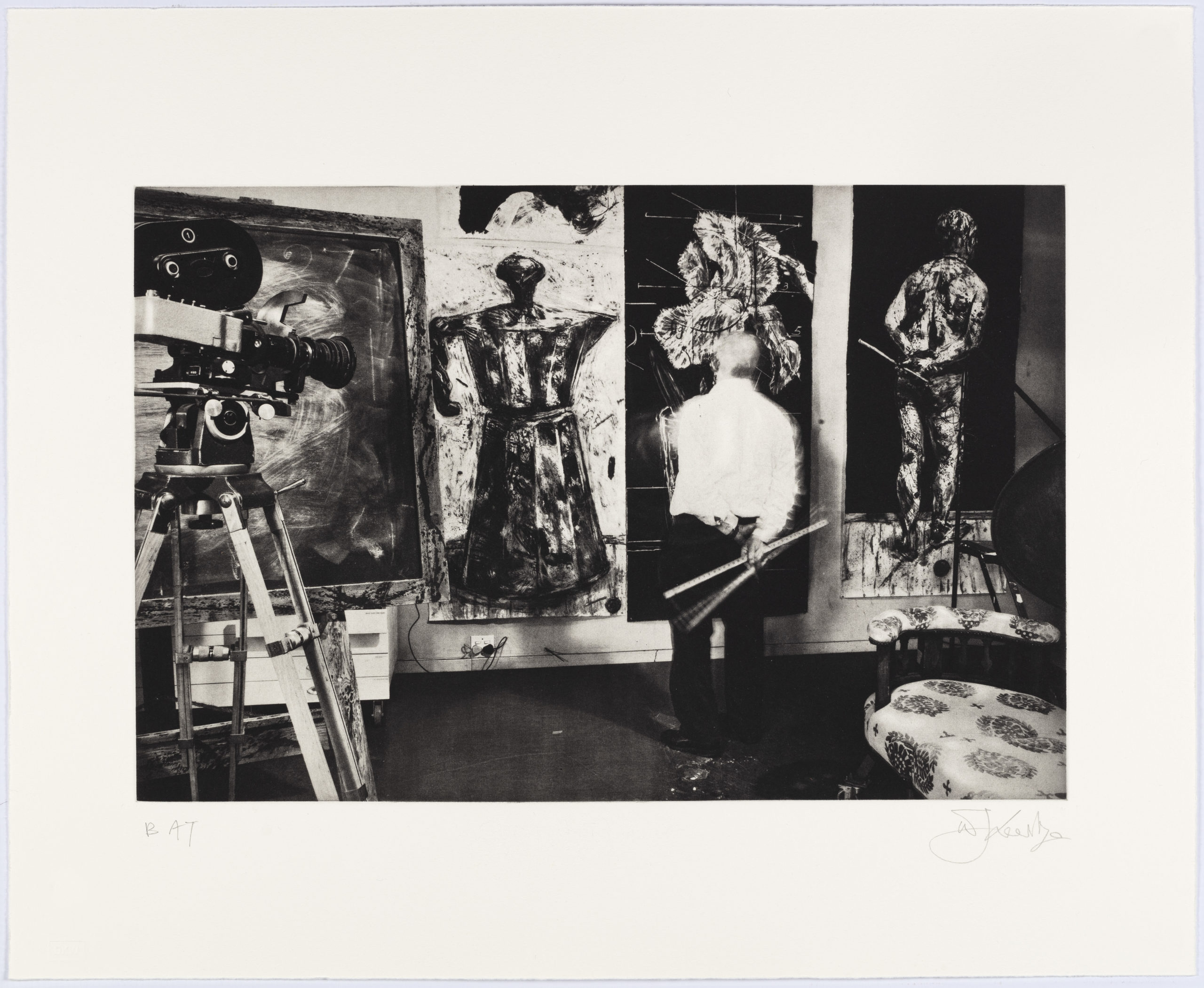

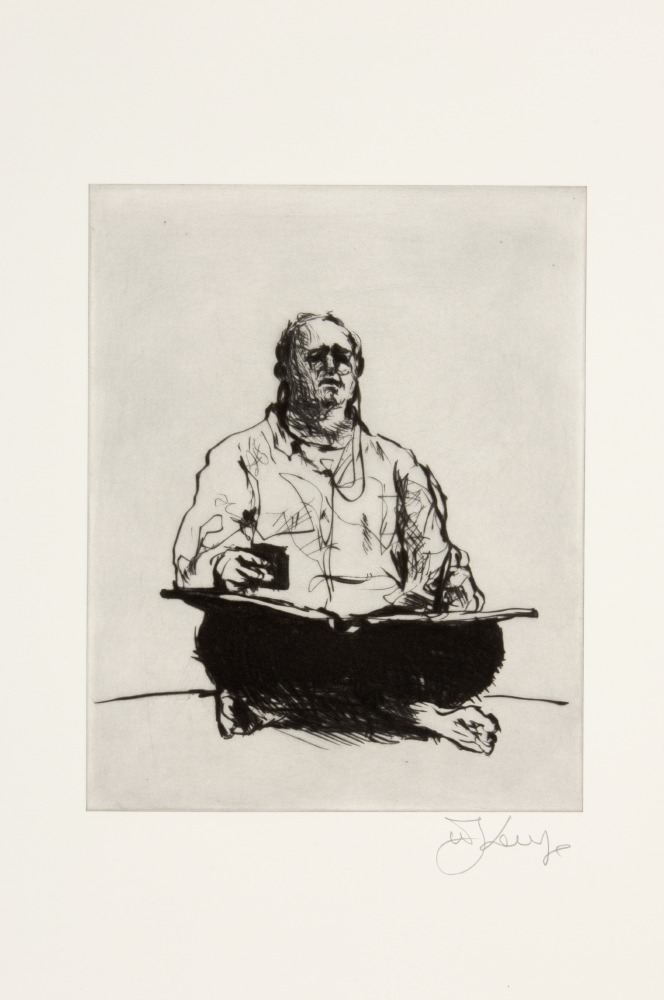

Studio Life Series

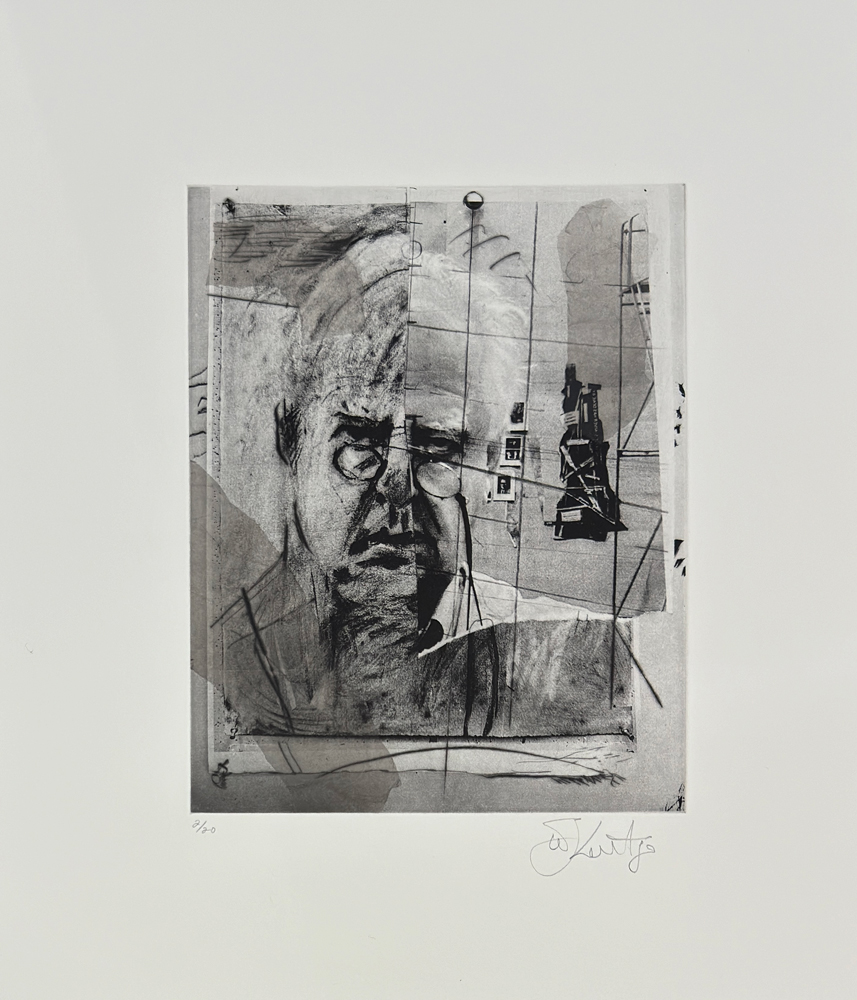

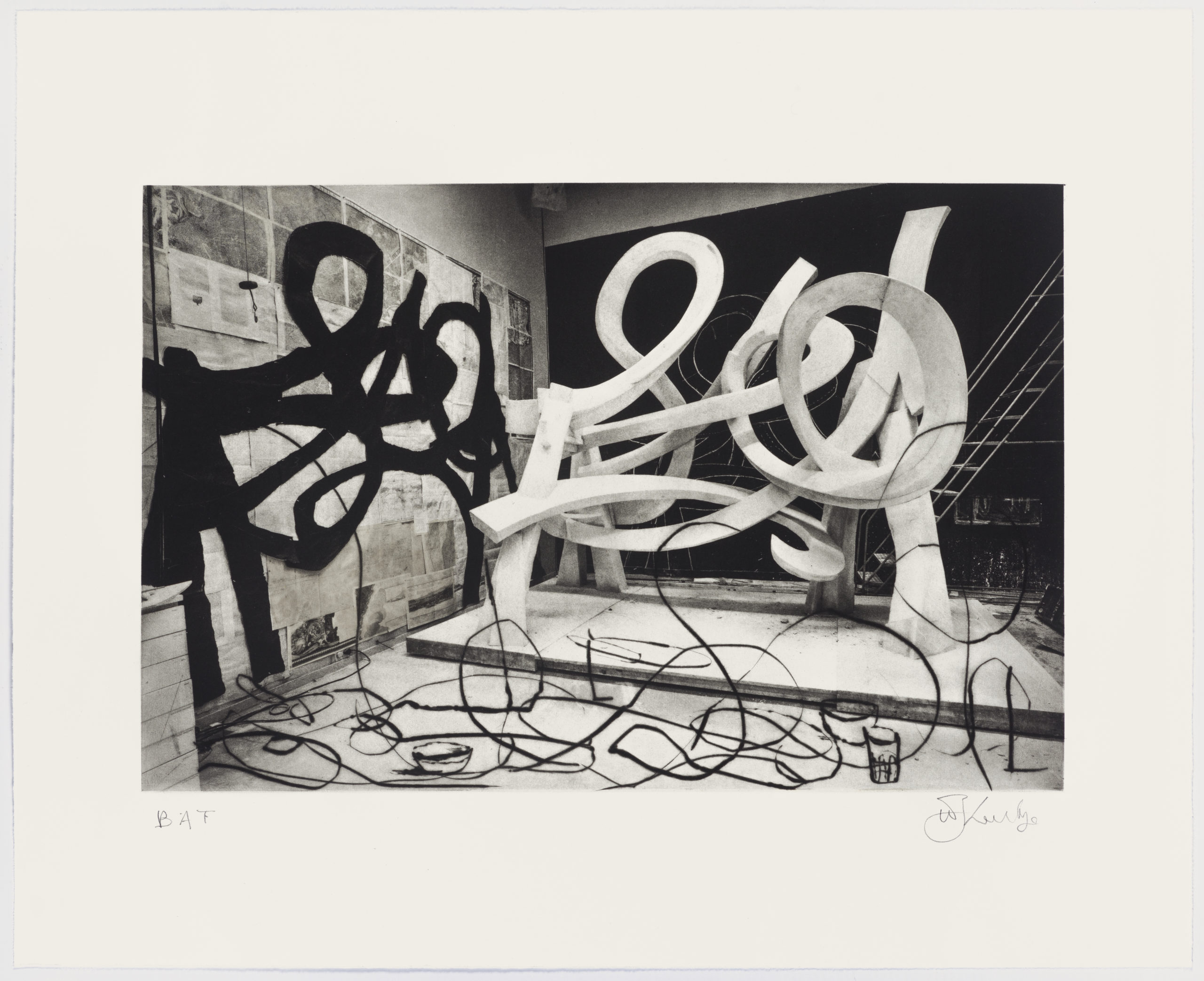

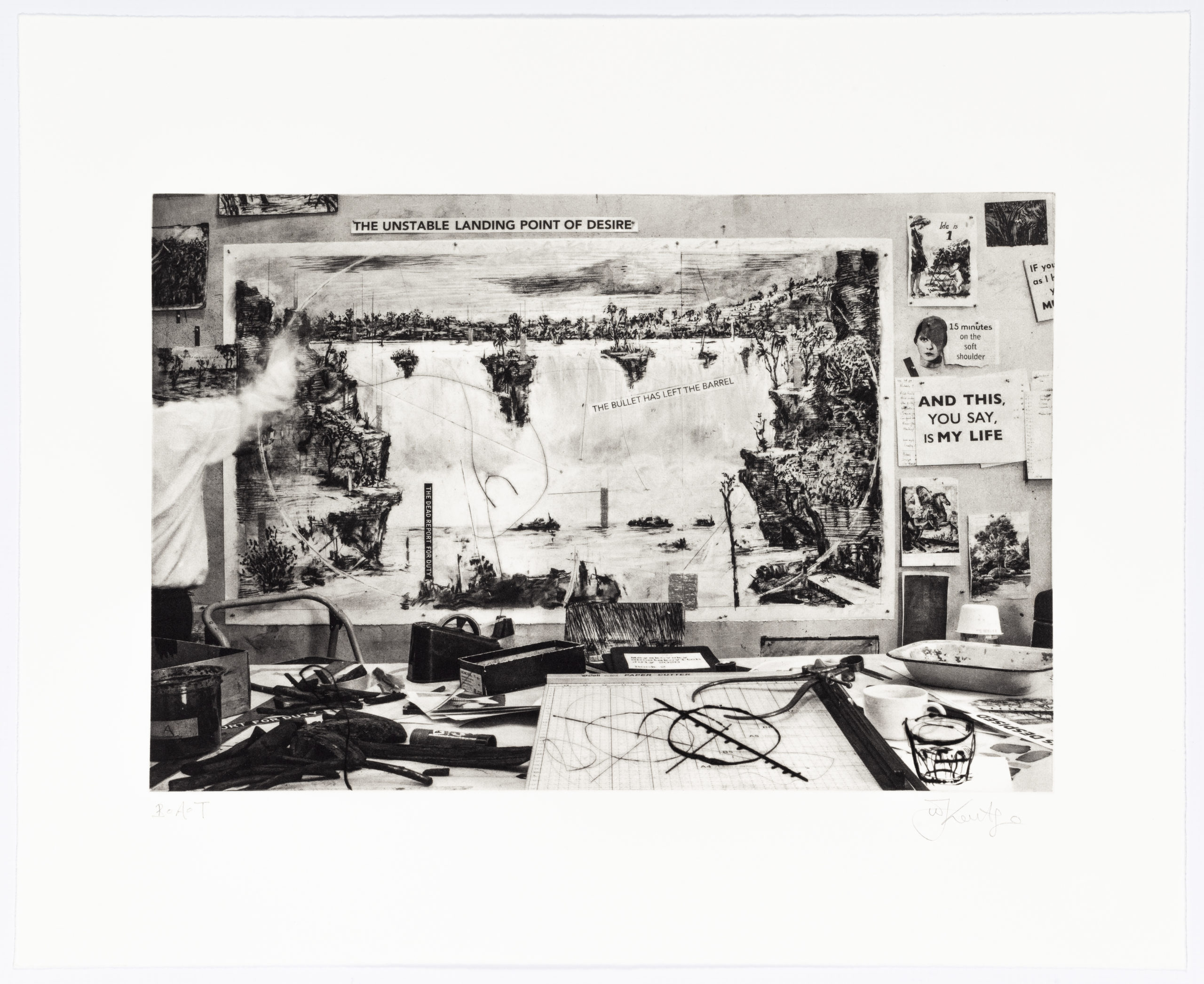

Studio Life Series consists of twelve photogravures which draw on stills from a nine part film series titled Self-portrait as a coffee pot. The imagery shows how he creates intricate, wall-sizes charcoal drawings of the vistas from his studio home in Johannesburg. Three of the films were screened at the recent Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). The photogravure images start from the beginning of lockdown in South Africa and continued while he was preparing for his Royal Academy exhibition which opened in London in September 2022

Loading more artworks...

Available Prints In Series

Loading more artworks...

Other Available Prints

This selection lists all of the editioned works by William Kentridge that are not in selected series.

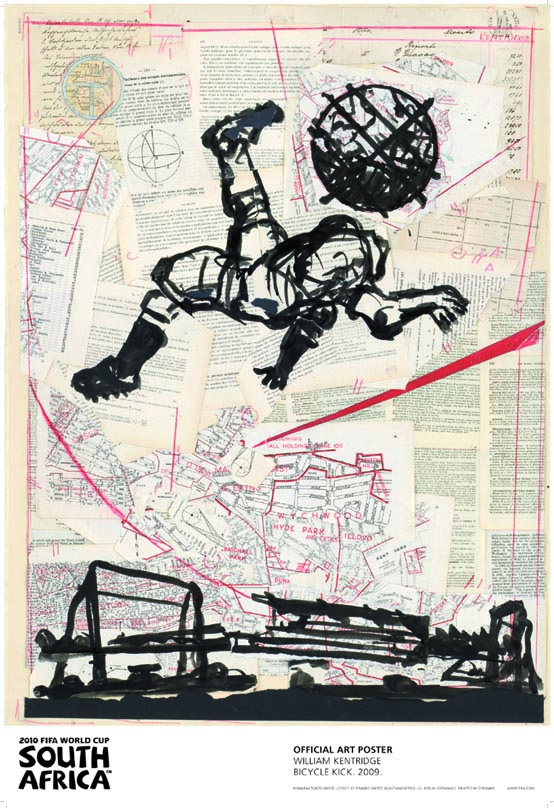

Read more ▼William Kentridge (b.1955) is a multidisciplinary South African artist – a printmaker, a director of the theatre and opera, a draftsman and an animation filmmaker. One might call him a maverick of the arts for the unparalleled ways in which he combines old and new artistic mediums, such as film and charcoal. While he does not define himself as a “political artist”, Kentridge is widely regarded as the go-to contemporary South African artist whose work cannot be detached from his country’s recent history and fraught present.

His reading of ‘Politics and African History’ while studying at the Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg inspired him t0 reject the traditionalist position from which art was taught at the time in South Africa. In his own words, he was told that “to be an artist was to paint with oil on canvas”. He took evening classes in etching, through which he started to grow as a visual artist who largely deals in black and white.

While many artists dabble in printmaking on the side of their practice, Kentridge is a modern pioneer in the medium – drawings and theatre projects regularly emerge from his prints. For Kentridge, printmaking is in itself a multi-disciplinary practice. He says that “there is also a way of thinking of an etching as an extraordinary, ridiculously complicated form of animation, different states of the plate when you know that you will rework them”.

Loading more artworks...

News (51)

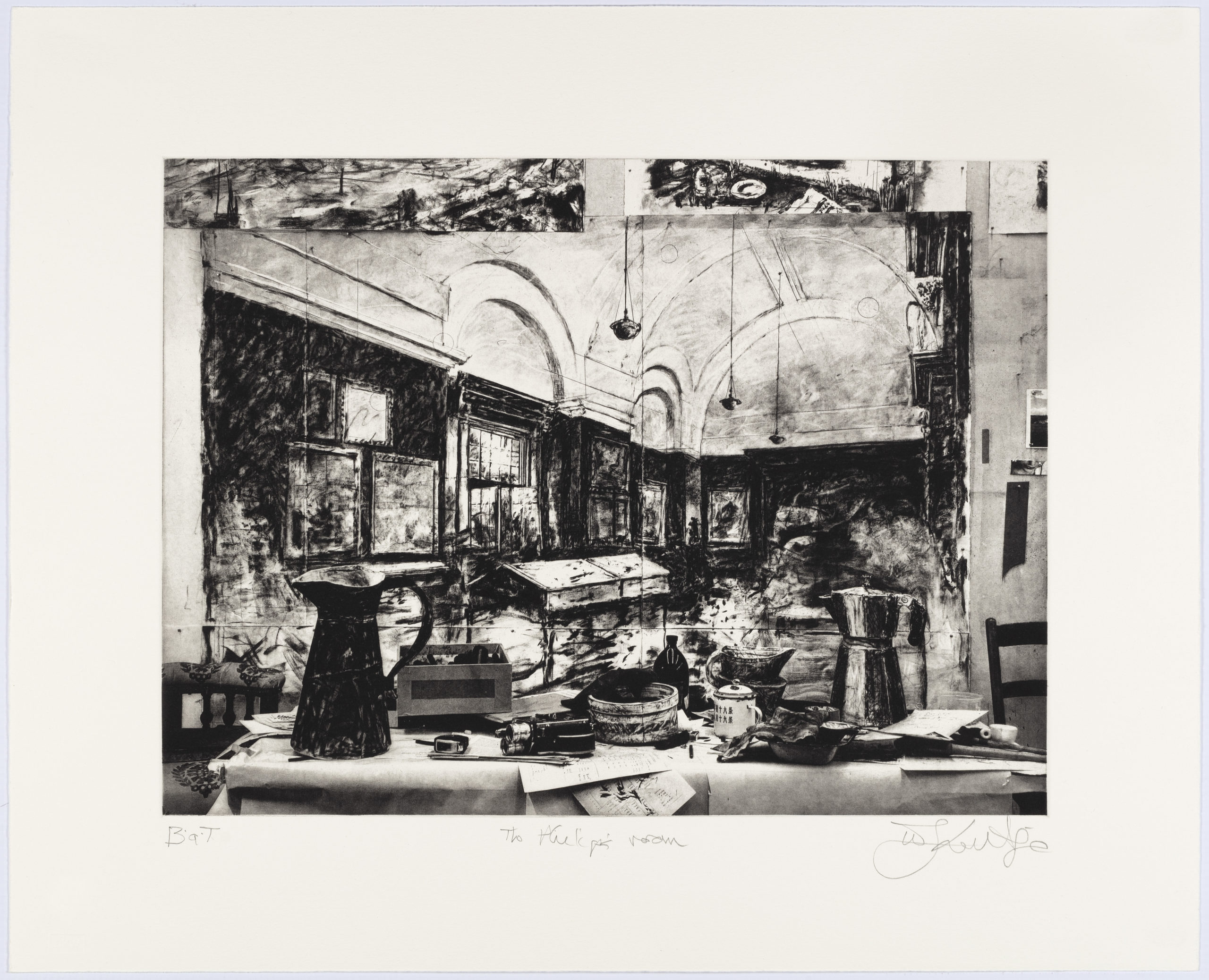

FILM | William Kentridge | The Philips Room (2020) Photogravure

Oct. 20, 2020https://www.youtube.com/embed/z6iiWiJ8OZY Watch The Philips Room (2020) by William Kentridge being wiped and printed by editioning printer Kim-Lee Loggenberg, with a...

Tags: Arts on Main, David Krut Workshop, DKW, Film, Marisha Flovers, video, william kentridge, William Kentridge (Universal Archive)William Kentridge Sound clips from 1997 CD-ROM published by David Krut

Feb. 21, 2018Listen to William Kentridge speak in a series of sound clips extracted from a CD-ROM published by David Krut in...

Tags: Artwork, podcastWilliam Kentridge on Work, Life & Influences | Sound clips from 1997 CD Rom

Jan. 31, 2018In 1997 David Krut published a CD Rom on Kentridge, which was the first major publication on his work, presenting...

Tags: Artist, Charcoal Drawing, influences, podcast, PrintmakingWilliam Kentridge -If you have no eye-The Full Creative Process

Mar. 30, 2015On Saturday 28th of March the David Krut Workshop (DKW) hosted a demonstration for William Kentridge's If you have no...

William Kentridge Walkabout with Harvard University Art History Students

Nov. 20, 2014William Kentridge treated Art History students from Harvard University to a walkabout at the David Krut Print Workshop (DKW) at...

Tags: william kentridge, William Kentridge (Universal Archive), william kentridge studioOn View at Carnegie Hall | Johannesburg in Print, Curated by David Krut Projects

Oct. 9, 2014Johannesburg in Print | Curated by David Krut Projects On View: October - December 2014 We are excited to announce...

Tags: carnegie hall, Music, South Africa, ubuntu, William Kentridge (Universal Archive)Amandla: A Revolution In Four-Part Harmony Neo Muyanga & William Kentridge’s Second-Hand Reading at BRIC’s “Celebrate Brooklyn!” (NYC)

Jul. 17, 2014July 25, 2014 · 7:30 PM CELEBRATE BROOKLYN! @ Prospect Park Bandshell FREE Doors open at 6:30pm. 20 years ago,...

Tags: Africa, BRIC, Brooklyn, Festival, Prospect Park, South Africa, William Kentridge (Universal Archive)David Krut to Participate in the Year’s E|AB Fair, NYC

Jul. 14, 2014The Editions | Artists' Books Fair is coming back to NYC this Fall, 2014! Stay tuned to find more news...

Tags: 2014, art fair, E|AB, E|AB FairAssembling William Kentridge’s Linocut Trees

Feb. 28, 2014The work above is one of William Kentridge's new linocut trees, titled Lekkerbreek. The image is constructed from individual...

Tags: LinocutWilliam Kentridge – The Refusal of Time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dec. 6, 2013October 22, 2013 - May 11, 2014 William Kentridge (South African, b. 1955). The Refusal of Time (detail), 2012. Five-channel video with...

Tags: Installation, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, william kentridgeImages from Multiplied 2013

Oct. 31, 2013From 18 - 21 October David Krut, Luke Crossley and Jacqueline Nurse represented the David Krut Projects team at Christie's...

Tags: art fair, London, multipliedTHE PRINT SHOW at Ebony Cape Town, Installation Images

Jun. 18, 2013Here are a few installation images of THE PRINT SHOW, a collaboration between David Krut Projects and Ebony Cape Town....

Tags: Collaboration, Printmaking