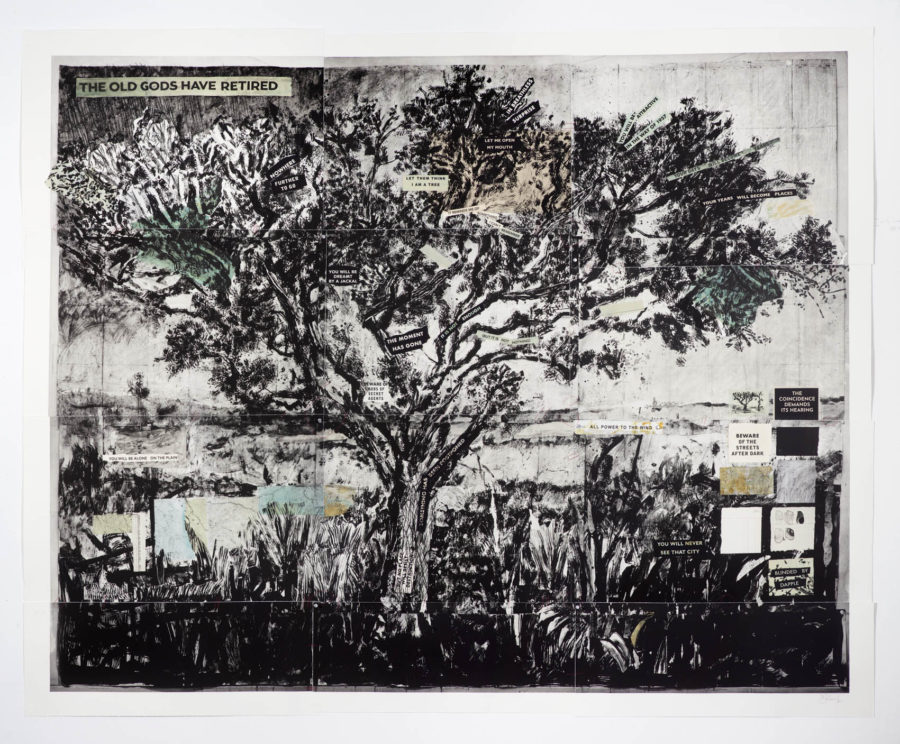

The Old Gods Have Retired

Trees have played an important role in the development of Kentridge’s artistic lexicon and have been present in his work in a variety of forms, the power of the trope ringing out in different ways through a number of Kentridge’s bodies of work.

Kentridge has spoken frequently about the influence that images and ideas of trees have had in his life, and the ways in which these have become integrated into his work. In a lecture given at Berlin Mosse in 2014, Kentridge talks of the “tree as lehrstück” or the “lesson play” associated with Bertolt Brecht’s epic genre of theatre that explored acting as a route to learning; of the reluctance of a Swedish boat builder who worked on Kentridge’s Black Box project to use German oak, because of the shrapnel contained in the wood, and of the strange sense of “trees still living holding the history in them.” In the same lecture, Kentridge ruminates on our ability to “meet the tree halfway” in our construction of meaning around it, and on the porousness of knowledge.

In another lecture, delivered as part of his Humanitas Visiting Professorship in Contemporary Art at Oxford University in May 2013, Kentridge remembers mishearing a word – tree-search, instead of t-shirt – and suddenly “in half a second, a whole etymology and history and examples of tree-searches unfolded.” In another instance of mis-heard words, Kentridge’s memory of his father working on the Treason Trial, or the “trees and tile” to his boyhood ears, has yielded innumerable metaphors for understanding the relationship between what we know and how we experience the world, piecing together fragments and fitting them together as we wend our way through the complex forest of history. In a conversation with Jane Taylor, Kentridge also recalls his frustration as a child that two white stinkwood trees at his family home in Houghton seemed to refuse to grow big enough to suspend a hammock between them, and his grief at the death of one of these trees during a lightning storm, many years later when he returned to occupy the same home in which he grew up. Over the course of decades, Kentridge has drawn out the metaphorical richness that trees offer to sense-making within his multidisciplinary practice: “a tree you could disassemble into its pages and hide in a library, like hiding a book in a forest.” The fact that Kentridge’s hometown and the locus of much of his work is Johannesburg, often called the largest human-made forest, cannot be overlooked.

The Old Gods Have Retired is quite literally pieced together from fragments on a monumental scale. These feature pieces of maps, segments of hand painted chine-collé and collage papers and dislocated text in addition to the twelve overlapping sheets printed from direct gravure

plates that make up the image in totality.

The origin of this large-scale, multi-plate work stems from an even larger drawing of a tree – much larger than life-size – that Kentridge created as part of his process of developing the Studio Life series of nine films, in which the drawing features many times. The films and series of photogravures have their origins in the COVID-19 pandemic, which was a time of global fragmentation, with great distances between people suddenly becoming very apparent and often problematic in a world in which travel was severely restricted. This monumental work speaks to that time, not least through scraps and splinters of text that appear almost as branches and leaves of the tree, and can be reconstructed in multiple ways, with various lyrical results and implications.

The map fragments, which feature greens and blues that depart in a gentle way from Kentridge’s habitual Constructivist red, speak most directly to

the distances between people, to the overcoming of distance that was required by multiple collaborators in order to realise this work, and to the reconfiguration of relationships that necessarily occurs in such times of disruption. As part of the tree, these figments of map, fragments of text and colour, also introduce a concept of time that reaches beyond the linear. As Stephen Clingman has so aptly put it, in writing of Kentridge’s tree drawings: “The tree is rooted in the earth and reaches towards the sky. It presides in time over our lives, yet also encodes the mystery of seasonal

cycles and metamorphosis. Its wood becomes the paper on which drawings of trees appear.”

The creation of The Old Gods Have Retired speaks to Kentridge’s deep understanding and appreciation of the concept of collaboration and his

uninterrupted engagement of multiple collaborators to realise large-scale projects, regardless of sudden and unforeseen changes in circumstance.

In the context of trees, The Old Gods Have Retired touches on the groundbreaking research by Suzanne Simard and her own collaborators, that reimagines the forest as more than just a collection of trees. Rather, the forest is understood as an interconnected and relational community, in which the traditional dominance of the concept of competition playing the biggest role in evolution gives way to coevolution and symbiosis as essential components of the progress and success of all the role-players contained within the picture.

Text by Jacqueline Flint, 2022 |

Published by Jillian Ross Print and David Krut Projects |

Collaborating Master Printer: Jillian Ross |

Photogravure by Steven Dixon, Luke Johnson, Alex Thompson (Edmonton, Canada) with Zhane Warren (Cape Town, South Africa)

Editioning and image development at David Krut Workshop (Johannesburg, South Africa)

Editioning printers: Kim-Lee Loggenberg, Sbongiseni Khulu, Roxy Kaczmarck and Sarah Judge

| Artist: | William Kentridge |

| Title: | The Old Gods Have Retired |

| More about: | William Kentridge |

| Year: | 2022 |

| Artwork Category:: | Editions & Multiples published by David Krut |

| Media & Techniques: | Photogravure with sugarlift aquatint; direct gravure; drypoint and chine with found ledger paper and handpainting |

| Printer: | Jillian Ross co-publisher |

| Edition Size: | 20 |

| Sheet Height: | 175 cm |

| Sheet Width: | 210 cm |

| Availability: | Available |

| Framing: | Unframed |