29.07.16

In 2010, Artnet’s print specialist Deborah Ripley interviewed David Krut at the Projects gallery in Chelsea, New York, about his unique collaborative relationship with William Kentridge, which dates back to 1992.

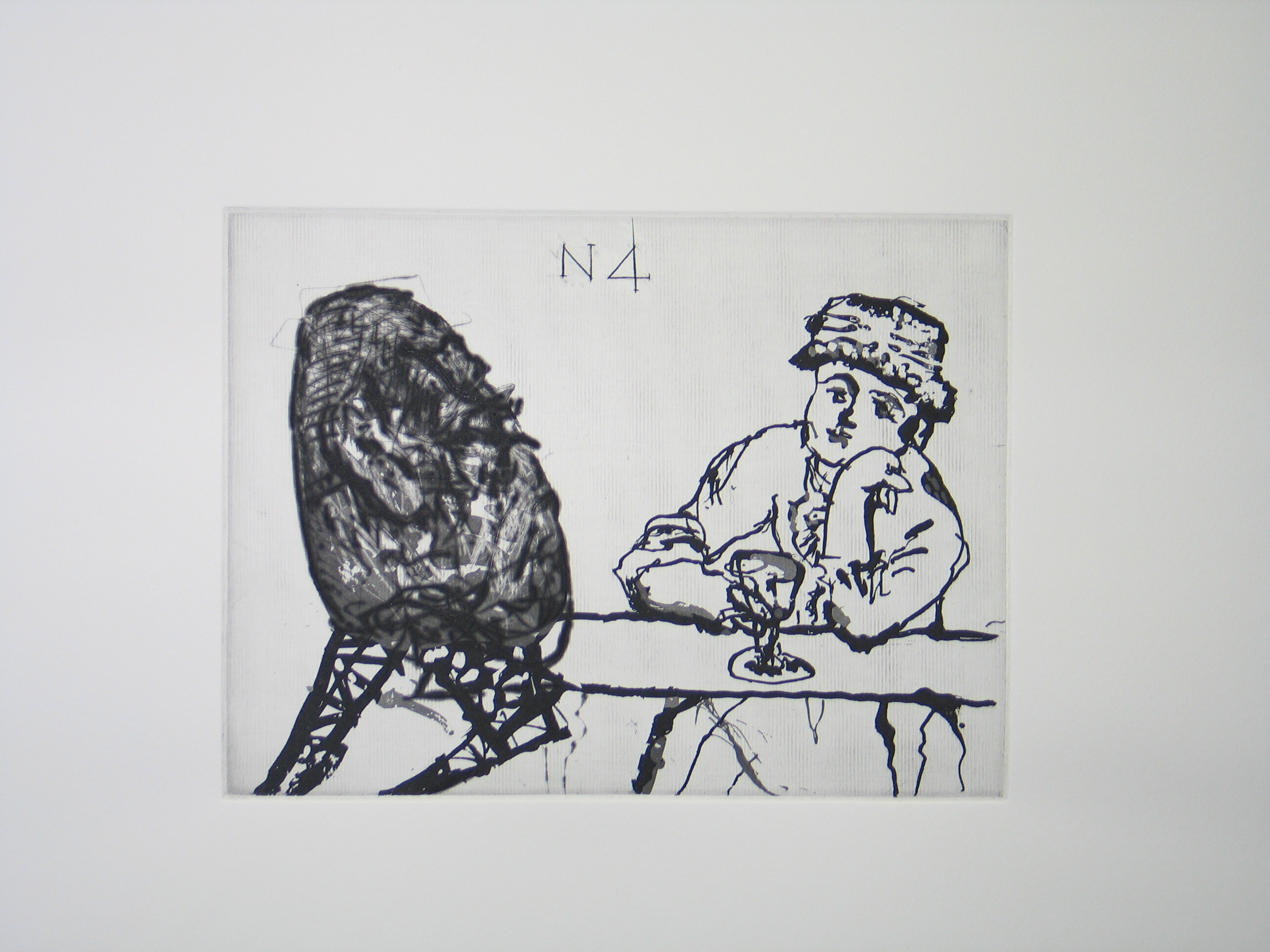

Kentridge had a major retrospective on at MoMA at the time and his production of Dimitri Shostakovich’s opera, The Nose, had just premiered at the Metropolitan Opera to rave reviews. Krut and Kentridge had just collaborated on a suite of thirty etchings – titled Nose – in connection with the opera, and Krut had published a catalogue of the prints, which was on display in the gallery.

This week, we revisit the interview to

Deborah Ripley: When did you first start working with Kentridge?

David Krut: I met William in 1992 at an opening in Johannesburg. We found out we had a lot in common and developed a friendship. At the time he was working with a guy who had a print shop 300 miles outside of Joburg who was innovative but not a practiced printer. Kentridge was going to go to England for an exhibition so I suggested he meet with Jack Sherreff, the master printer at 107 Workshop, to explore working really big. The large yellow print, The General (1993), was one of the first results. William worked with Jack on and off until 2000. I also introduced William to David Hockney’s printer, the fine intaglio printer Maurice Payne, and in 2001 we completed a marvelous set, “Zeno at 4 A.M,” which forms part of the MoMA exhibition. And now this project – set of 30 etchings, which encompass the ideas that developed into The Nose opera.

DR: How did “The Nose” suite of prints develop?

DK: After seeing Kentridge’s 2005 production, The Magic Flute, director Peter Gelb asked Kentridge to direct and design an opera. Gelb was familiar with Kentridge’s work; in fact he had collected his prints. Kentridge was intrigued by the famous Gogol story that follows the adventures of a pompous government official named Kovalyov, who wakes up one day to find that his nose has left his face and gone walking around St Petersburg.

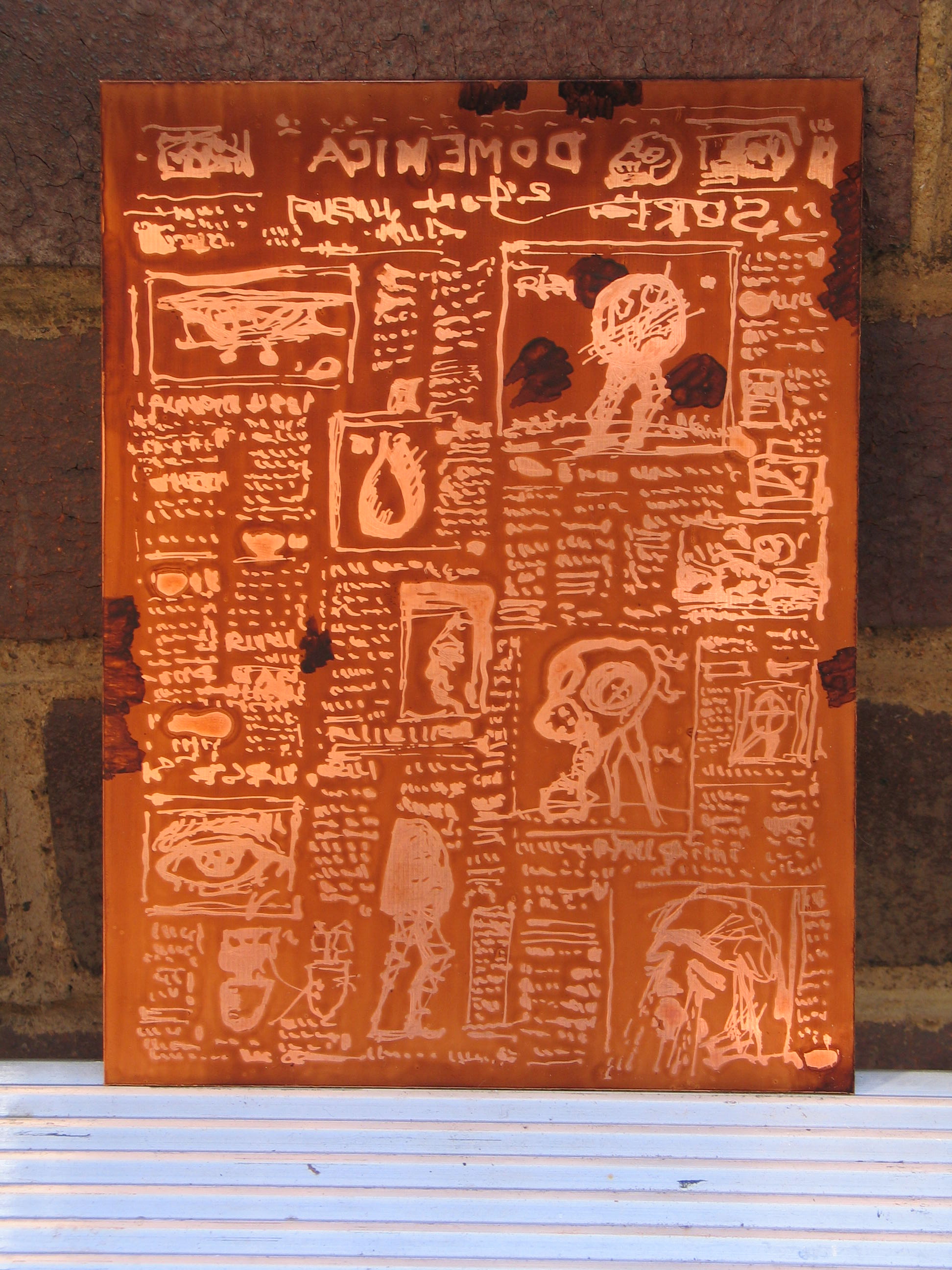

When Kentridge begins a project, he works through ideas intensively, starting with drawing on a copper plate. The prints are a way for him to think out loud to try on different ideas that will eventually lead to the opera.

Kentridge often uses art historical sources; he’s got a great collection of paintings of postcards, including Manet’s Bar at Folies Bergere, Ingres’ Olympia and Degas’ Absinthe Drinker. I went to see him on a Friday and when I came back on Monday, he had copied them all as gouaches and they became a starting point for the earlier prints in the series.

Kentridge works unbelievably fast. There are images of the Nose riding horses – Kentridge was making equestrian sculptures at the time, but he was also exploring this old Russian saying that is used to deny guilt, “I am not me, the horse is not mine.” As he went along, Kentridge decided to project Gogol’s story forward to the 1917 Russian Revolution and he used archival footage as a source. But he also decided to include allusions to Stalin’s purges of the 1930s.

DR: Is there an order to the 30 prints in the suite?

DK: The prints didn’t actually include the engraved number in the upper corner until the end. Just like Kentridge doesn’t storyboard his stop-animation films, he doesn’t know where he’s going to end up. He often puts down ideas and then finds ways to connect them. At the later stage he had the idea of what the opera was going to look like so the prints start to reference specific scenes.

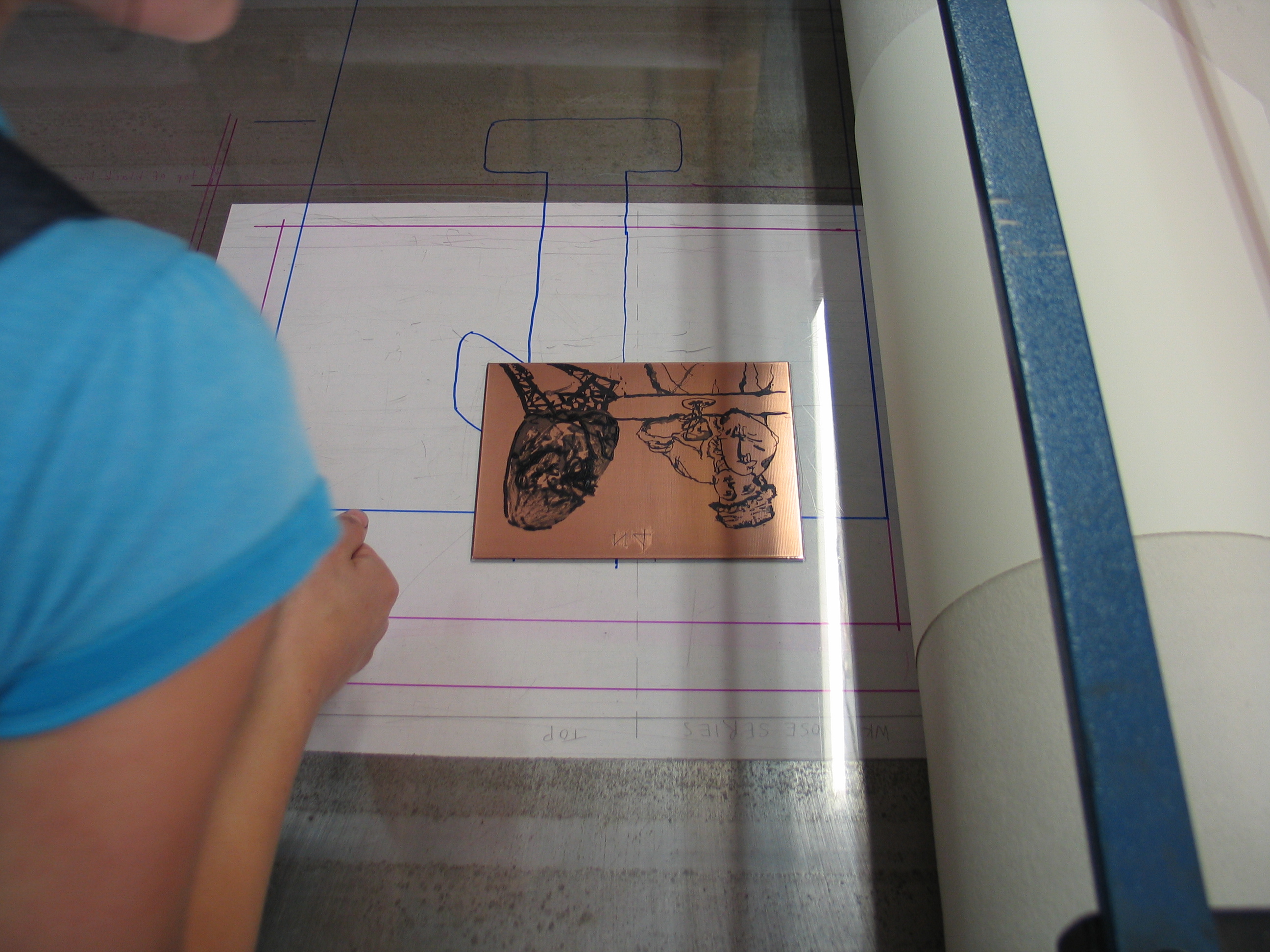

DR: Can you talk a little about the production of the prints?

DK: In 2006, when I told Jillian Ross, the master printer of my print workshop in Johannesburg, that she was going to be working with William, she was terrified. He’s the most famous artist in South Africa and a brilliant printmaker – he taught etching at the Johannesburg Art Foundation. William looks at a plate and analyzes immediately what it needs. Unlike many artists, William considers printmaking on an equal level with all his other artistic activities – the MoMA show has over 100 prints.

When we started this project in 2005, it was very low-key. We’d receive three or four plates and pull proofs and then send the plates to London to be steel-faced. That got too laborious (and there was an incident when a plate went missing in the post) so we installed a steel-facing machine in South Africa. Because we had this March deadline (coinciding with the retrospective and opera), the pace picked up and Jillian and William developed a rhythm of working together to finish on time.

We’ve come a long way from when this gallery was a print shop ten years ago, with a press operated by Randy Heminghaus, and we had a rather casual way of working.

DR: How many sets will be kept intact?

DK: I am reserving 10 sets in the hopes that museums will acquire them. Curators need to understand the importance of his prints. William’s work is so cerebral, and these can be an interesting support in understanding his animated films, theatre etc.

DR: What do you think your contribution has been to the understanding of Kentridge’s work?

DK: Prints are all about the popularization of knowledge. The dissemination of prints allowed art audiences outside of South Africa to get to know Kentridge’s work long before he had an international following and a big gallery. Prints have first and foremost allowed communication at all levels in society and I hope this is especially true with these prints.

Click to read the interview in full.

Since collaborating on the Nose series, David Krut Workshop and William Kentridge have combined creative efforts on the Universal Archive project and embarked on a collaboration involving large woodblocks with images selected from the 550m frieze in Rome, Triumphs and Laments, which detail Italy’s culture and history.

The Nose series was exhibited in full at the Museum Haus Konstruktiv in Switzerland. Click here to read about this multimedia show, which is accompanied by a comprehensive book, The Nose, for sale at the David Krut Bookstore. There is an essay by Kentridge in the book, which details his interest in the original story by Russian author Nikolai Gogol in 1836.

This Facebook Print Feature gives a snapshot of the original Nose story to which the Nose etching series relates.