27.11.15

Blogger: Jessie Cohen

Visual artist and cultural producer Stephen Hobbs is well known for his war-design-inspired public artwork through which he probes the very real, and often very ugly, meaning behind “urban development” in fraught social spaces on the African continent. It is no surprise that Hobbs’s interest in defensive architecture began in Johannesburg, his hometown, during South Africa’s pivotal moment of social change in 1994. Since then, Hobbs has applied a curious and critical eye to his city, playing with literal “inner-city self reflections” (buildings seen within buildings) to prompt a metaphorical “social self reflection” on the supposed transformation of the so-called “Rainbow Nation”. One finds very little colour in Hobbs’s work, which tends to follow a grey tonal scale, depicting the state of the country in a palette stripped of delusional optimism.

As co-director of the public art company Trinity Session, Hobbs mostly makes large-scale murals and projections, directly inserting his artwork onto building facades with the hope of inspiring people to re-read their city. Recently, Hobbs decided to down-size, creating a modest suite of four 37×32 cm prints, individually titled Pillbox, Signs of a Transforming City, Dazzle Cloud and Kaleidoscope. Collectively, the suite is called Buildings, bombs, bunkers and clouds. For Hobbs, “the pleasure of working within such an intimate size is the opportunity to execute [his] ideas across a broader scale pendulum.”

A lot of complex ideas are compacted into these images, making the task to unpack their meaning all the more demanding. So I met with Hobbs at his Trinity Session studio to speak about the prints. I anticipated some resistance, seeing as the subject matter is, broadly speaking, an exploration of methods of obscuring meaning, but the artist was keen to share his process.

With arms stretched behind his head, Hobbs tests the full spring of his back rest and surveys the sets of prints, which he has neatly laid across his desk. He tells me that “each work is a distillation of a core set of themes – architecture, war, camouflage and dazzle – which run through twenty-odd years of work.”

One glance at Mr. Hobbs and it is evident that these themes are not only integral to his practice, but key to his personal presentation. Like a soldier who won’t remove his uniform out of patriotic loyalty, Hobbs’s dedication to his practice extends to a self-set uniform comprising of camouflage/combat pants and a black shirt imprinted with a Hobbs dazzle/camouflage design. “It creates two simple fields of vision on my body,” he explains with a boyish grin. Essentially, Hobbs is what he arts.

While he digs the gear, Hobbs insists that he is not interested in war-related structures and designs for its own sake. Rather, he is drawn to “the ironies, the follies, the sheer hubris of these war relics” (Hobbs) and uses them predominantly to comment on contemporary South Africa, which remains structured according to apartheid’s architecturally and geographically imposed enemy lines.

To explain his thought process for Buildings, bombs, bunkers and clouds, Hobbs takes me back to a trip he made three years ago when he visited a cluster of concealed First and Second World War bunkers and gun batteries in Robben Island on the Cape Peninsula. The structures never went to war, as such, and remain hidden relics in the rural landscape. Hobbs went to gather source material for an exhibition called Permanent Culture, which was held at the David Krut gallery in Newlands earlier this year. The same source material has also proved important for the etching suite.

During the trip, Hobbs photographed structures which caught his eye. The following images inspired his Pillbox etching:

To explore the tactics around building a pillbox, Hobbs made a mock-up in his studio:

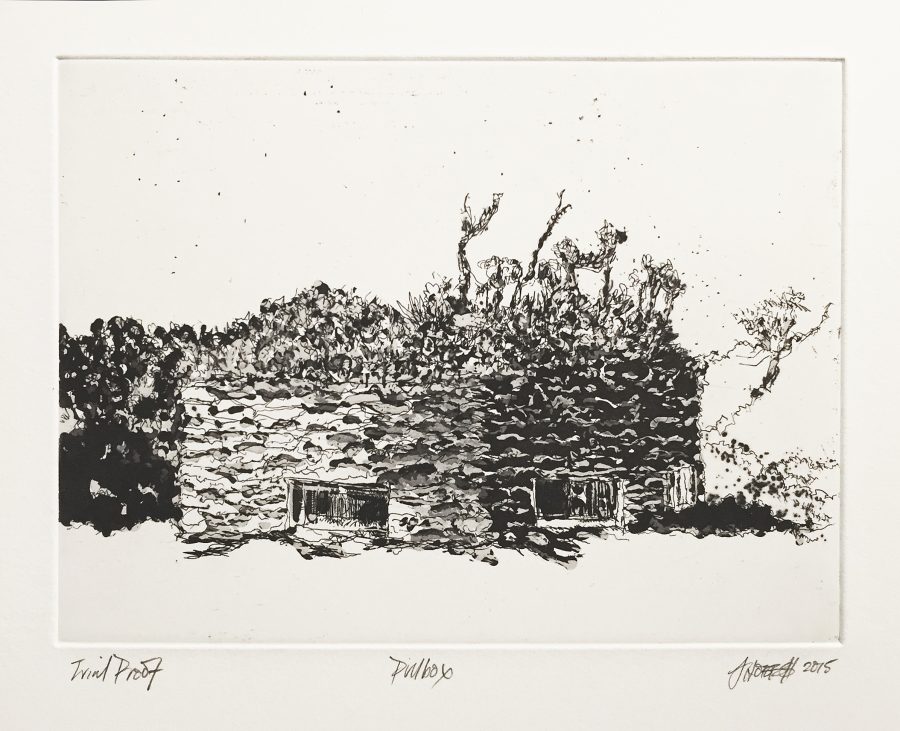

Pillbox

For the translation of Pillbox, Hobbs traced his photograph of the pillbox in Robben Island and then etched it using hardground and aquatint sugar lift. He is drawn to the irony of the structure, which is obsolete but stands strong, as if to assert an obstinate permanence on the South African landscape. It is striking that, in the print, this brutalist piece of architecture takes a charming, cottage-like form. The eye-sore becomes cute and turns into something inviting, serving as a powerful trigger to re-examine defensive architecture for its deceptive, surface qualities.

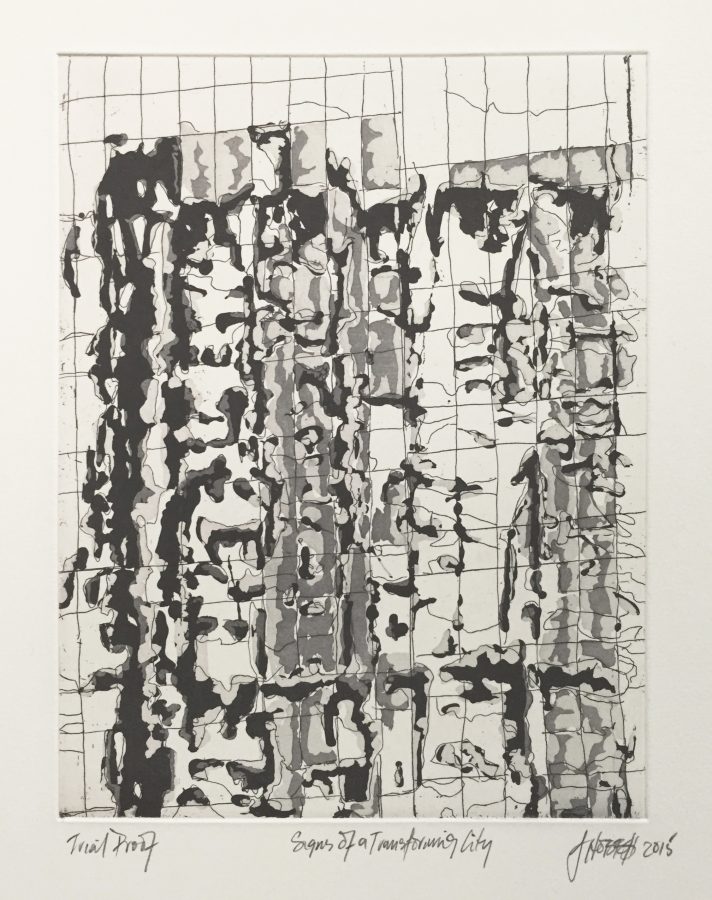

Signs of a Transforming City

The title of this print plays to the ironies of South Africa’s geographical transformation, or the lack thereof. It is inspired by photographs taken by Hobbs in Johannesburg in 1997 as part of a series which he called The Mirage City:

Hobbs: “When I took these shots I was a young man negotiating a city at its apex of transformation largely due to white flight, which started in the seventies when black resistance started to escalate. I was looking at what kinds of disorder were left in the wake of white flight and tried to understand what these new edges and definitions might be in terms of occupation, decentralisation and urban decay.”

At this critical time in South African history, Hobbs started to examine the relationship between glass curtain buildings and reinforced concrete buildings in Johannesburg’s CBD, noting their beautiful formal interplay but also the striking effect “as one drives past and starts to read the surface of the reflection as it ripples and moves, creating a kind of mimesis, a look of camouflage, a sense of disruption”.

In 2001, Hobbs submitted a photograph from The Mirage City series to the Johannesburg Art City Campaign, which offered twenty artists potent visibility around the city of whom Hobbs was one. This was the result:

By placing an image of intermingling colonial and apartheid architectures on a billboard on a building in the CBD in 2001, a symbolic dismantling of the post-1994 city grid was subtly depicted. In the photograph, which went on to inspire Signs of a Transforming City, an internal city reflection serves as an illusionary fantasy for old institutions undergoing transformation from permanent and imposing to temporary and unstable. For Hobbs, it is “a metaphor for the post-apartheid condition in which we are witnessing a slow crumbling of old institutions that we are yet to rebuild.”

How does the concept of “defensive architecture” resonate in 21st century South Africa?

Hobbs: “You just have to look around at the urban planning of a city like Johannesburg and its attendant townships to see what I’m talking about: the physical separation mechanisms – the buffer land placed between the city and its surrounding spaces, by which I mean golf courses, fences, rocks even. I recently noticed that under a bridge in Cape Town, large spiky rocks have been placed to prevent homeless people taking shelter there. This was done in the name of creating ‘cleaner cities’. We cosmeticize our cities according to global tourism agendas and, in doing so, we undermine our societal health. This spatial problematic ignites a curiosity in me about urban politics. Two decades after the supposed dismantling of apartheid and South Africa is still structured like a war-zone.”

Hobbs recently travelled to America to lecture on defensive architecture. He also made prints relating to urban development issues pertinent to South Africa and parts of the States.

Click to read more about his trip and to view the prints:

Click to watch Hobbs’s keynote lecture on defensive architecture at the Penny Stamps lecture series in Detroit:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H9rWUGp07YE&list=PL65E5E2AD5123E43A&index=10

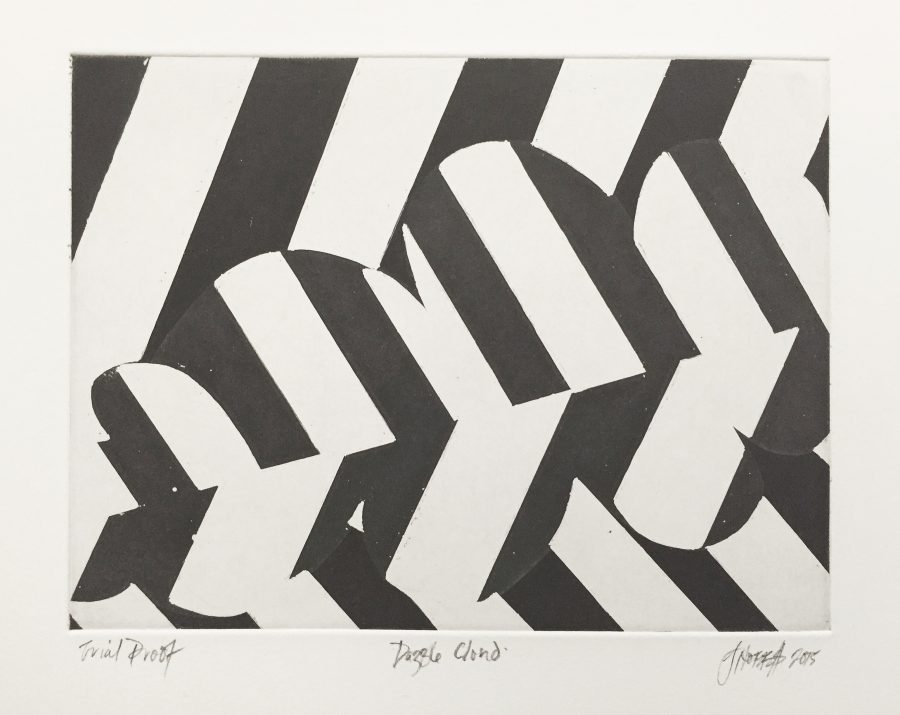

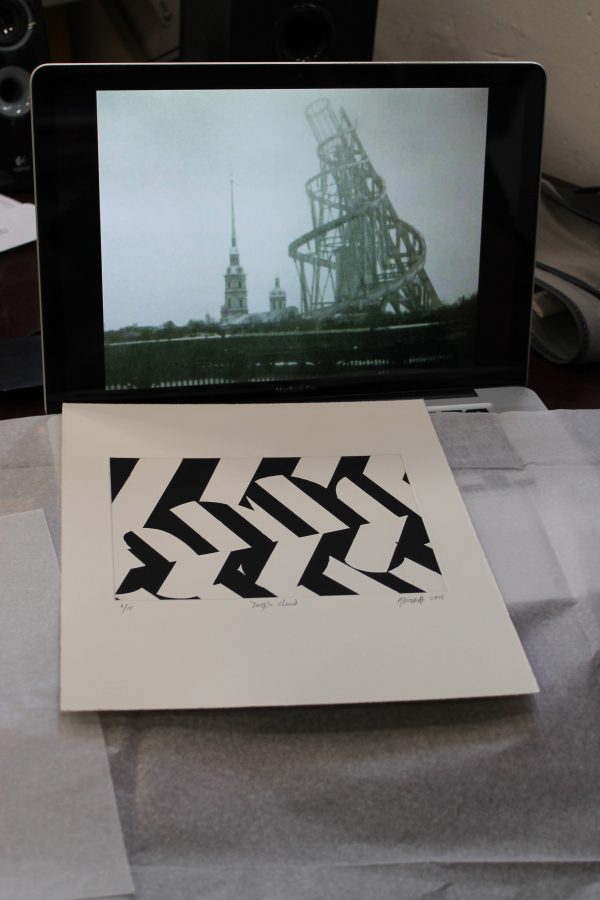

Dazzle Cloud

Dazzle Cloud is inspired by the vision and folly surrounding Russian artist and architect Vladimir Tatlin’s design for a towering symbol of modernity in 1919, known as Tatlin’s Tower, which went no further than a large-scale model.

The tower was envisaged as 400m high and, riding the coattails of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Tatlin wanted to project propagandist images from the building onto the undersides of clouds. Hobbs has played with Tatlin’s idea, specifically in relation to clouds and projection, since 2009 when he exhibited a dazzle-patterned sculpture of a cloud attached to a Tatlin Tower model at KZNSA Gallery for a solo show, titled D’Urban.

It is interesting to see the piece because, when re-conceived in print form, the association with the Tower is not directly drawn.

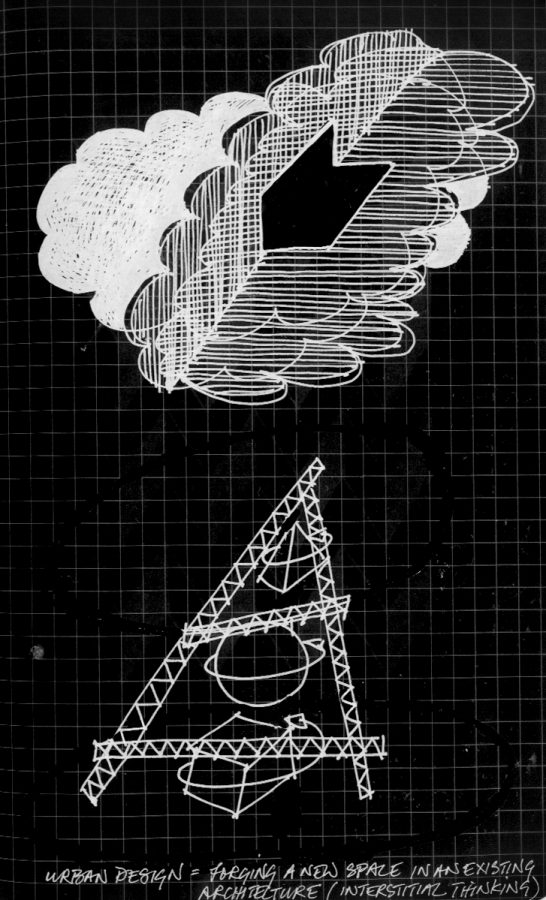

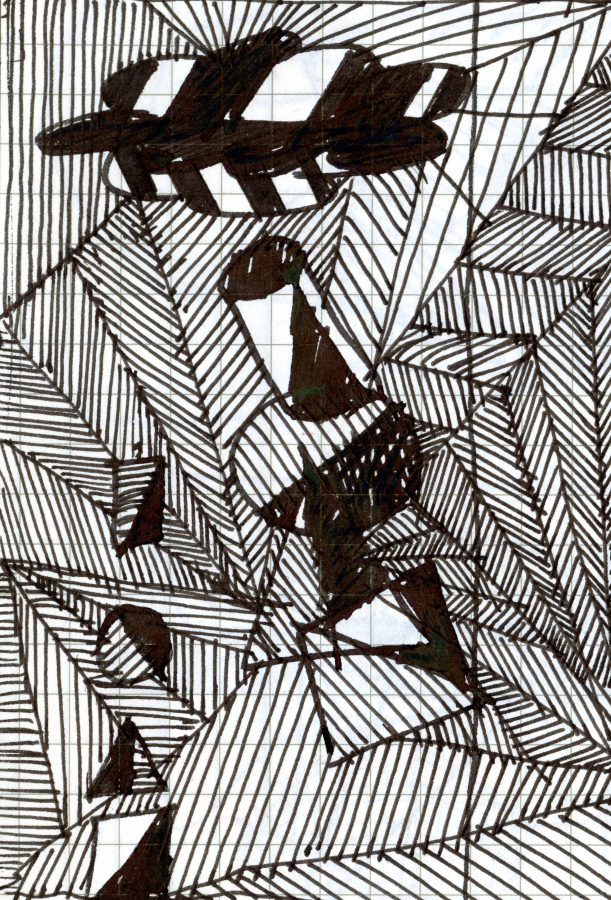

Hobbs did a number of preparatory drawings for the dazzle cloud sculpture-installation:

I was intrigued to understand the pull of camouflage and dazzle for the artist.

Hobbs: “To me, the folly of camouflage with its dark purpose of obfuscation is completely gripping”.

Jacqueline Nurse, writer for David Krut, interprets Hobbs’s use of camouflage as “a metaphor for understanding tactical consciousness in urban planning” and sees Hobbs to be commenting on South African dynamics of “inclusion/exclusion, visibility/marginalisation [as well as] the politics of separation and attendant power relations”.

Hobbs expands on this analysis: “it is important to remember that at the time of WWI camouflage and dazzle were the latest technology. I’m interested in the role artists played to create deception in the battlefield – a very real and demanding task. This involved designing camouflage clothes for soldiers to blend into their surroundings and creating dazzle design for battleships, which was literally intended to dazzle the enemy through optical illusion.”

Why put dazzle on a cloud?

Hobbs: “The cloud is dazzled because I like to play with the possibilities of abstracting an already abstract idea. The abstract idea was the Tatlin Tower itself because Tatlin didn’t know how to build his vision. Even more abstract was projecting films onto the underside of clouds! In totality, nothing came of Tatlin’s vision except the homage that has been paid to it by hundreds of artists since. I love the idea of taking something geometric and solid, like dazzle, to transform a cloud into something concrete in its formal realisation. It’s about making the cloud the ultimate objective of the monument. It’s about a dream of reaching an audience in an innovative way – a fantasy shared by all artists.”

For the Dazzle Cloud etching, Hobbs de-contextualises the cloud from the Tatlin Tower and homes in on the neatly contained geometric form. The print has a rich physicality about it as both the cloud and the visual field in which it sits are executed in dazzle camouflage – “a delectable, bite-size iteration of dazzle with seduction in its simplicity,” even if the artist says so himself.

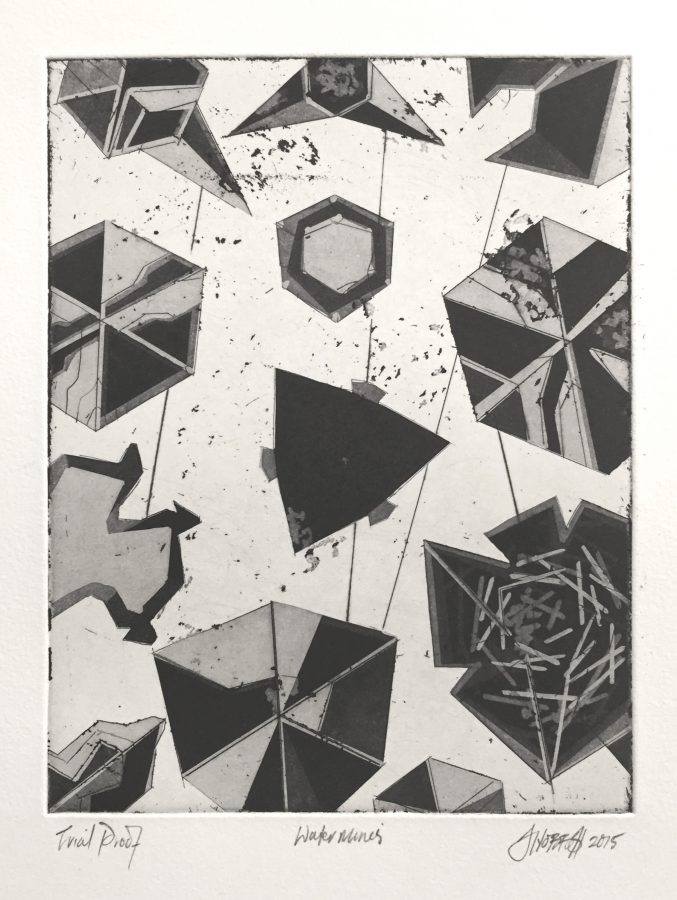

Kaleidoscope

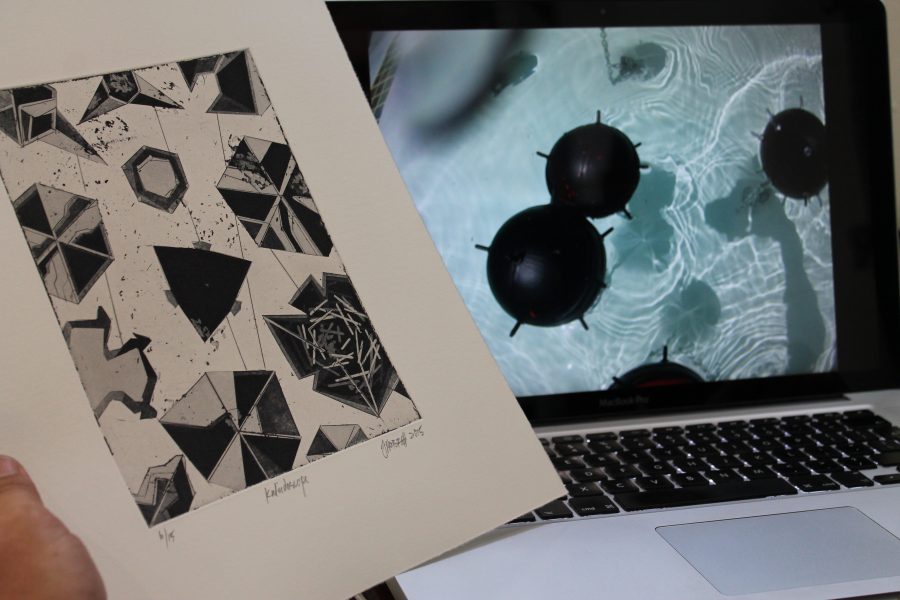

Kaleidoscope is based on a video installation piece from Permanent Culture (2015). For the piece, Hobbs projected a combination of documentary footage of U-boats and naval battles from the world wars along with homemade footage of an underwater contact mines set, which he made in his swimming pool.

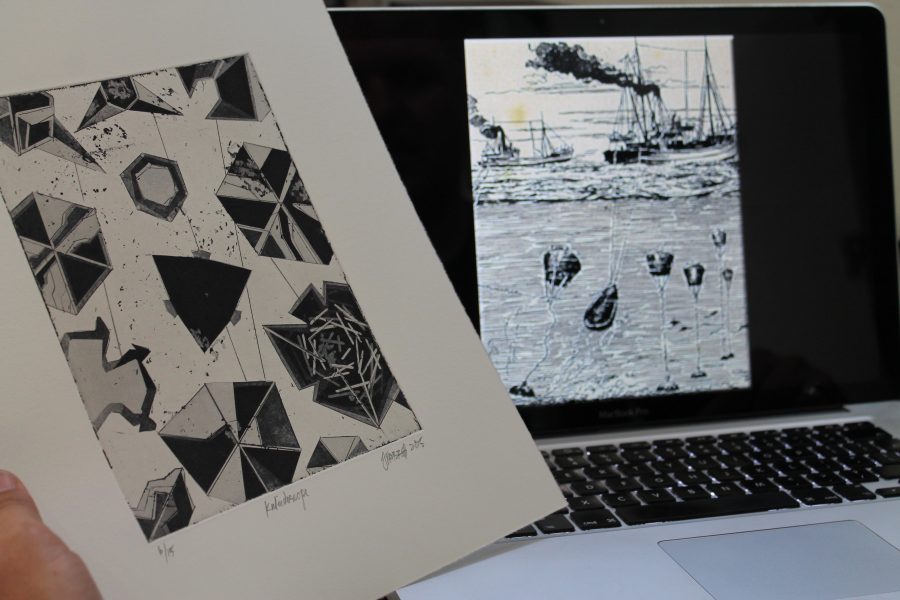

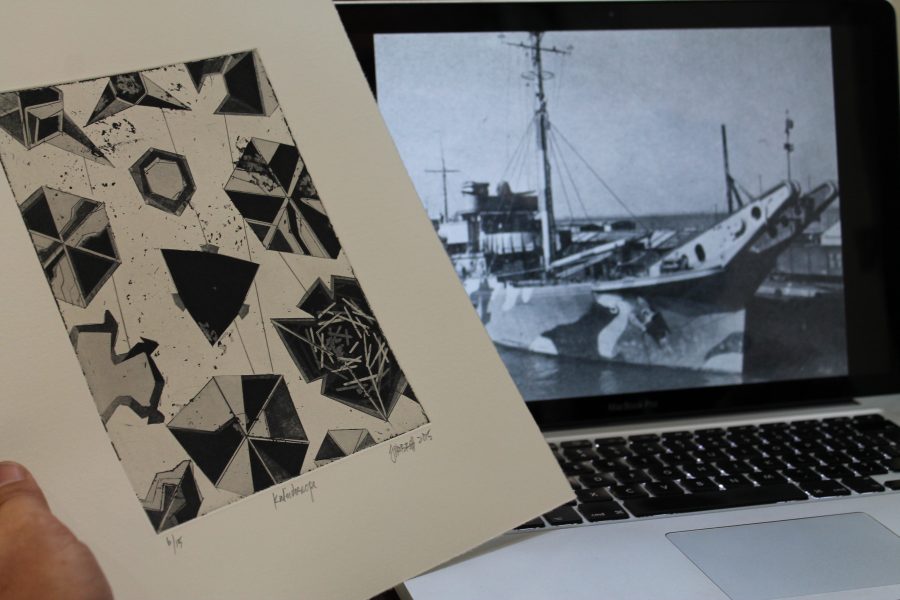

Hobbs shows me WWI and WWII images which are referenced in Kaleidoscope:

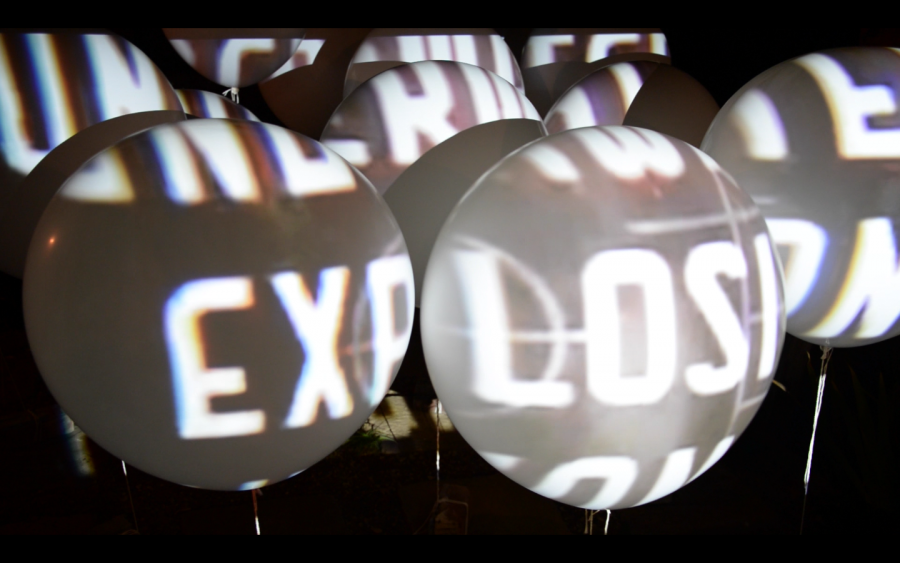

For projecting these images in his video installation, Hobbs used helium balloons to give the impression that the images were floating in the air, which lent a sense of temporality to their re-rendering.

The bobbing balloons attributed a disruptive, unstable quality to the footage:

For the Kaleidoscope print, Hobbs

In the final product, a fragmentary, kaleidoscopic vision of underwater contact mines is rendered. The viewer is invited to look as if from below at an abstracted, geometric imagining of deadly weapons and to observe their oxymoronic, delicate beauty.

Buildings, bombs, bunkers and clouds are available to buy individually and as a set. There are fifteen editions of each print.

Click here to view the prints on our website along with other works by Stephen Hobbs: http://davidkrutprojects.com/artists/stephen-hobbs