The following is a statement made by Aida Muluneh about her participation in the group exhibition, The Divine Comedy, Contemporary African Artists (2014) hosted and curated by the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art which showcased her chromogenic colour prints titled The 99 Series (2013):

Inferno is made of history, not only of a country but of self, of exile, of bloodshed, of loss, of mourning, of bitterness, of broken hearts and broken wings. The inferno is not down below; it is here, ever-present, next to us, in our memories and in our minds. It is made of delusions, of prostration, of hiding behind masks to validate our existence and hidden agendas; it’s a mask we wear to fool ourselves and others in an attempt to get ahead, yet we are void in our survival.

We live in the gray cold existence, uncomfortable like the dirty snow of western winters or like the polluted skyline of what we call Ethiopian modernity. Pulled between the past, the present and the future, we wrap ourselves with forgotten heritage and dream of looking towards the future, but we are stuck looking into the past. For eternity we are toiling with rituals and ceremony, yet our past deeds are marked by unhealing wounds, the blood of false victory stitched by the threads of nostalgia. A story we each carry, of loss, of oppressors, of victims, of disconnection, of belonging, of longing to see paradise in the dark abyss of eternity.

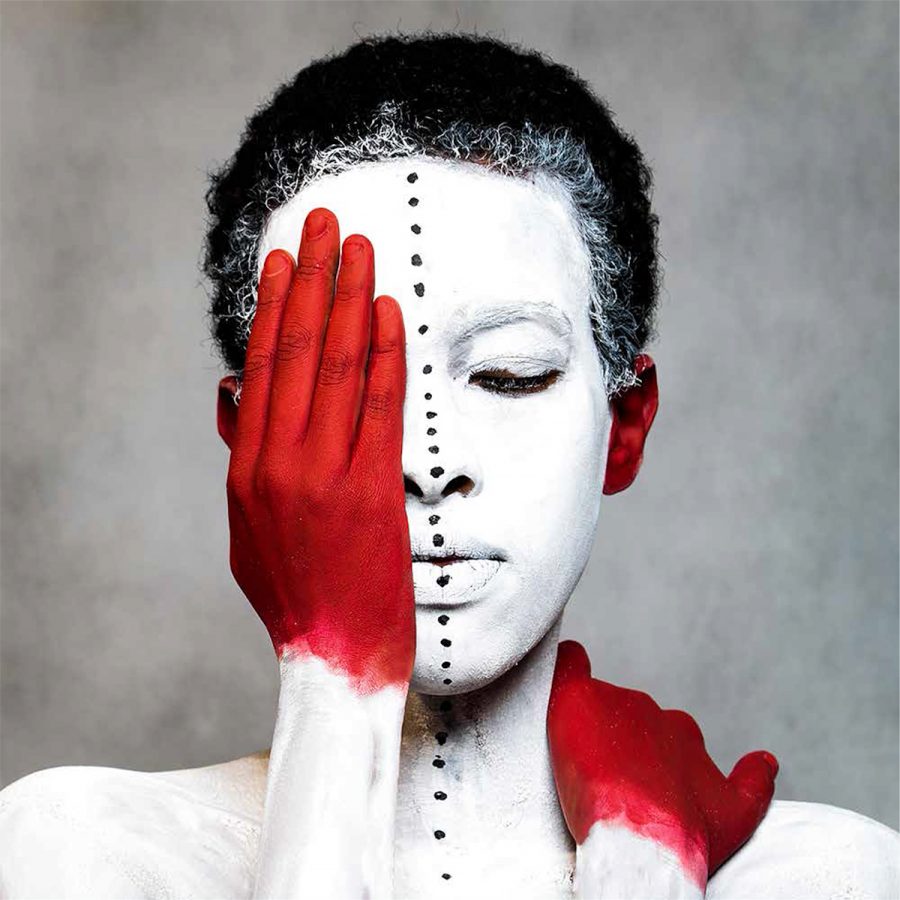

The 99 series, Part One, 2013, C-print

The 99 Series, Part Seven, 2013, C-print

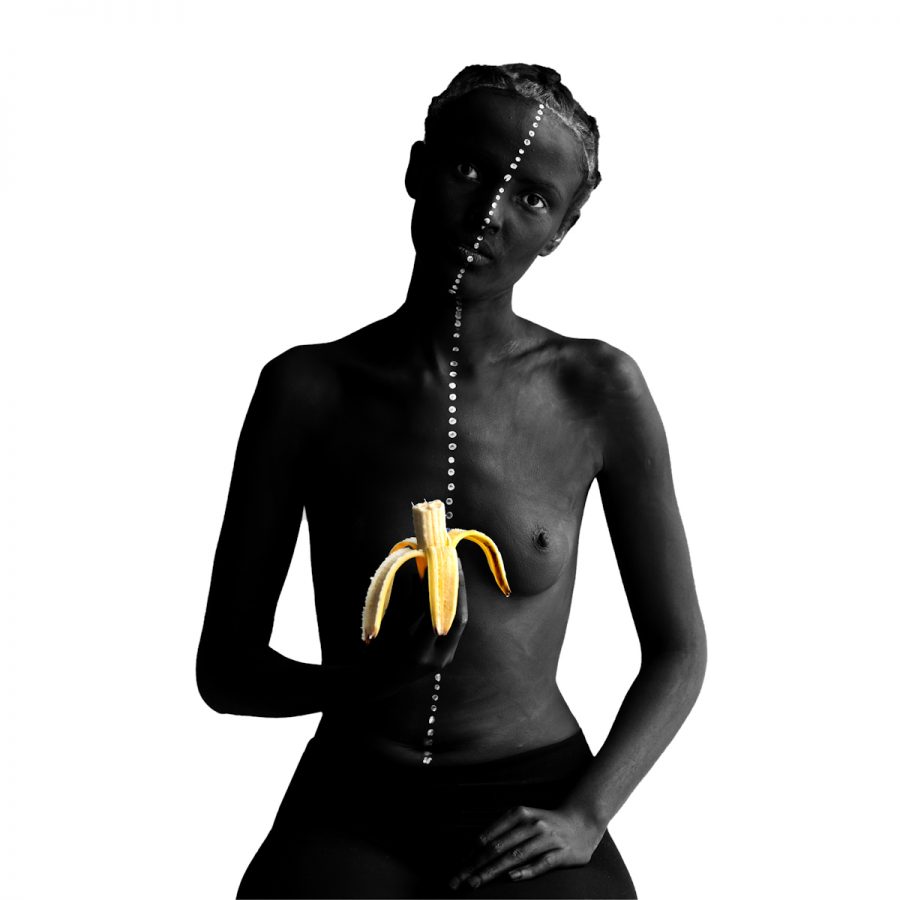

The 99 Series (2013), seen above, employs stylized visual language in its depiction of body painting. ‘Mask’ standing for ‘Portrait’ suggests modes of politically-charged representation: a whitened, minstrel face embodying ideas of deception and dissimulation share a common genus with the ‘veil’ and ‘double consciousness’ concepts that African-American sociologist, historian, and civil-rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois coined in 1903 to describe Black experience in America. Red-stained, bloodied hands speak to a history of colonial exploitation and internecine conflict. Dotted lines running down the middle of the face, neck, and back richly associate with lines of demarcated boundaries seen on maps with marked trails or planned roads that don’t as yet exist, rather transitional states and territories assigned for future exploration, conquest and exploitation.

Of the series, Muluneh says, that at the very least, she is trying to express what it is to be an African woman; to encapsulate gender and identity; to situate it within the territory of colonial experience, even while as an Ethiopian artist formed and informed by the African Diaspora, she is an outsider of sorts. She sees with the eyes of alterity or otherness because she was raised in Europe, the Middle East, and Canada, returning to settle in Addis Ababa after a thirty year absence. Moreover, Ethiopia is unique among African nations because it was never colonized by a European power (except for a brief five years of Italian occupation from 1936-1941). Muluneh is a cultural activist, an agent for change who began her working career as a photojournalist for the prestigious Washington Post, but finding it too limiting decided to pursue photography on a different level. After launching her artistic career by winning the 2007 Recontres Africaines de la Photographie European Union Prize in Bamako, Mali, she has taken a leading role in advancing the cause of photography in Ethiopia, where it is viewed with suspicion, a retention of the totalizing societal hold exercised by the Marxist-Leninist Derg Regime (1974-1987), followed by the military dictatorship of Mengistu Haile Mariam (1987-1991). The annual Addis Foto Fest held every December and founded and curated by Muluneh facilitates cultural production in the region, though it must seek European patronage to survive.

The 99 Series, Part Three, 2013,C-print

The Wolf You Feed Series (2014) broadens preoccupations taken up in The 99 Series. The imagery, at once more graphically-orientated and mediated by hand-painting is deceptively decorative. Its title is taken from a Native American Cherokee folktale of unknown authorship:

One evening, an elderly Cherokee Brave told his grandson about a battle that goes on inside people.

He said: “My son, the battle is between two ‘wolves’ inside us all. One is evil. It is anger, envy, jealousy, sorrow, regret, greed, arrogance, self-pity, guilt, resentment, inferiority, lies, false pride, superiority, and ego.

The other is good. It is joy, peace, love, hope, serenity, humility, kindness, benevolence, empathy, generosity, truth, compassion, and faith.”The grandson thought about it for a minute and then asked his grandfather: “Which wolf wins?” The old Cherokee simply replied, “The one that you feed.”

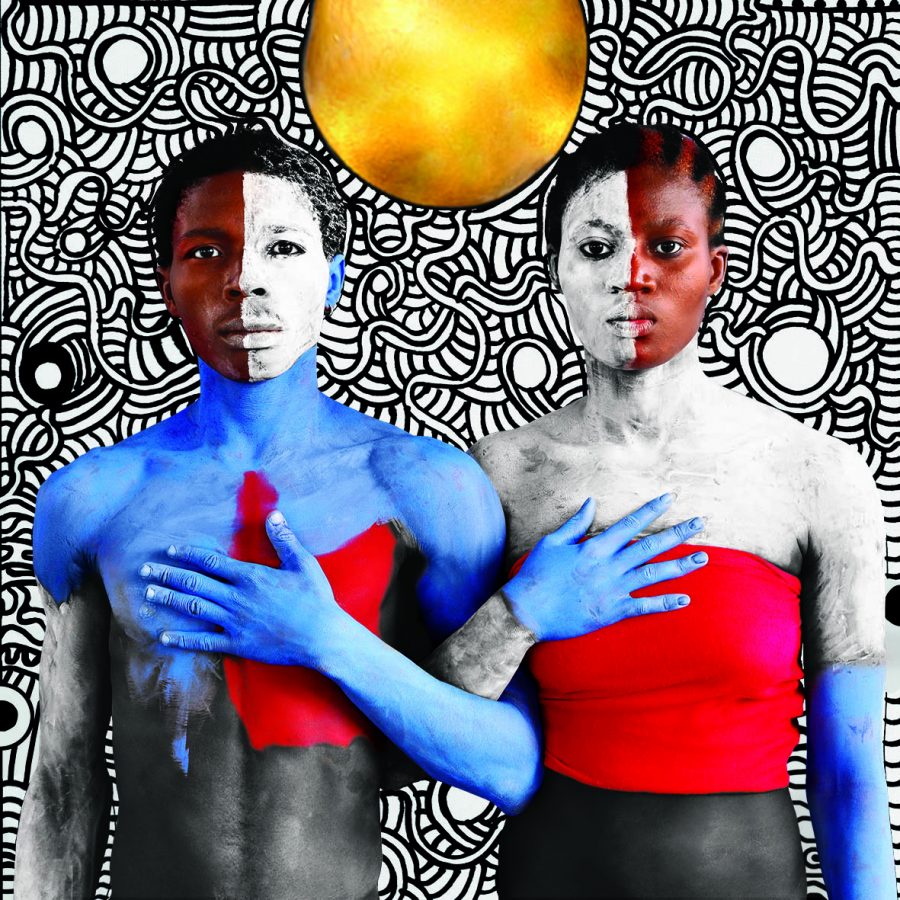

Liberte/Freedom, The Wolf you Feed Series, 2014, C-print

Revenge, The Wolf you Feed Series, 2014, C-print

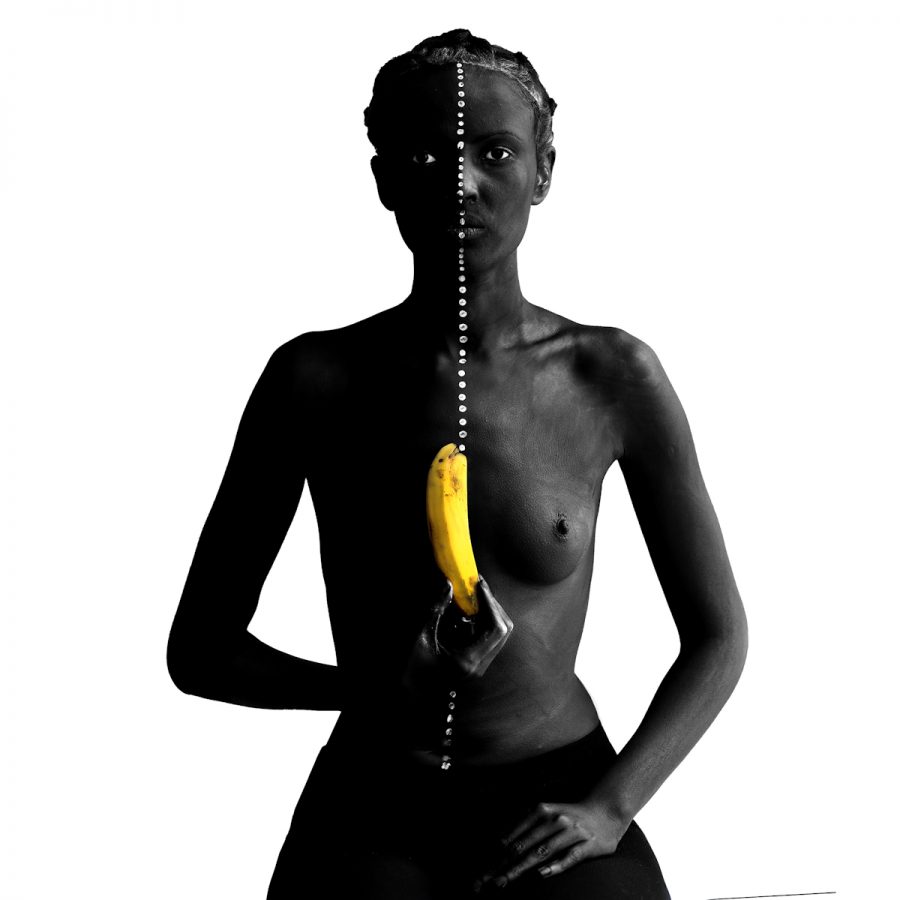

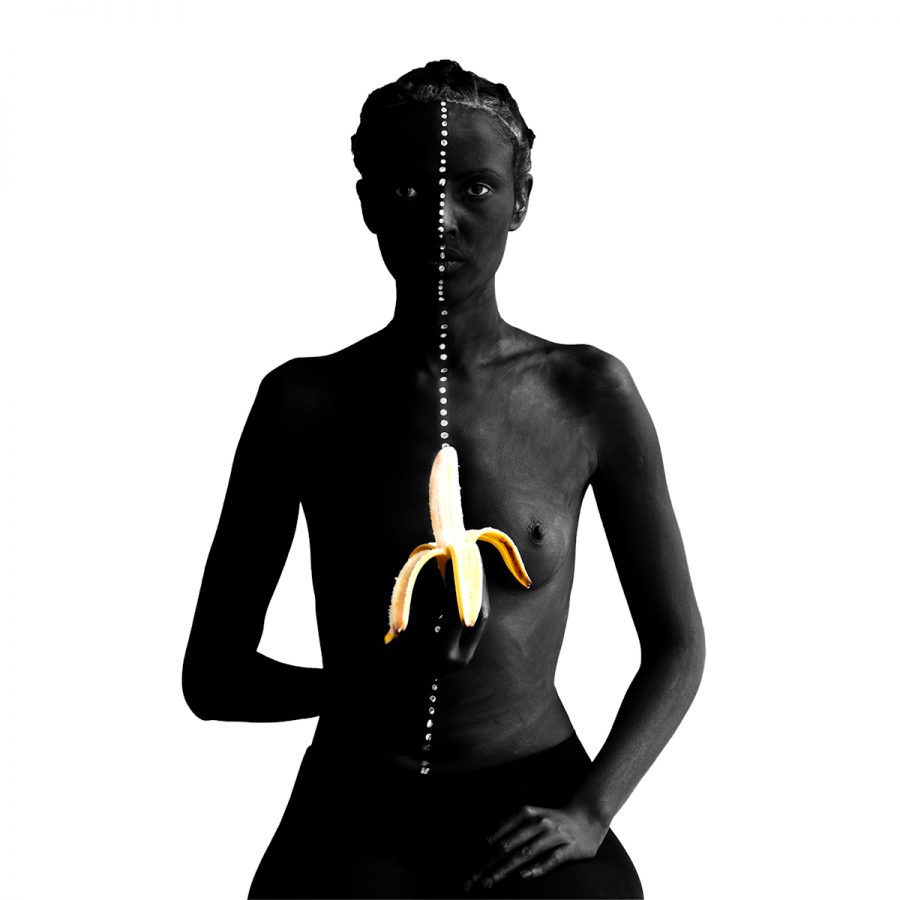

Parts One, Two and Three of the series, seen below, allude to incidents in recent football history when footballers in the European League were subjected to racial insults as fans of opposing teams threw bananas onto the field. Barcelona footballer, Dani Alves, responded by taking a bite out of the banana, treating the incident with the ridicule it deserved.

The Wolf you Feed, Part One, 2014, C-print

The Wolf you Feed, Part Two, 2014, C-print

The Wolf you Feed, Part Three, 2014, C-print

Text by Linda Kocovaos