Text by Jacqueline Flint

“Aesthetic thought is transversal to various languages and disciplines. It uses expressivity to bring together a language of relationships into the activities that take place. Aesthetic thought holds relational aspects of life together. Expressivity is a process that places things in relationships.” – Vea Vecchi

For Maja Maljević, her preparation for life as a creative began in her early teens, and her identity as an artist has been unfolding steadily from that point onwards. An artist through and through, Maljević is wholeheartedly and utterly committed to her practice, and to the honing of her craft over a number of decades and ongoing, forging her own expressive path as she goes. With painting as her primary practice, Maljević has also grown her repertoire of media to include printmaking, among others, and has been collaborating with the David Krut Workshop since 2007, making both unique and editioned works on paper. In her most recent body of work, Based on a true story, Maljević’s intuition and sensitivity as a practitioner is revealed through a departure in approach, that finds itself nestled within the broad context of the development of expression through abstraction from an historical perspective, and has been unfurling for Maljević personally over many years.

In 1971, French philosopher Michel Foucault delivered a lecture at the Tahar Haddad Culture Club in Tunis, dedicated to an analysis of the work of Edouard Manet. In this lecture, begun with the self-deprecating words, “It is as a layman that I speak to you of Manet,” Foucault presented the argument that Manet’s work, and in particular his 1863 painting Olympia, afforded a necessary rupture from which modern art could spring. The birth of the “picture-object”, or of painting released from the constraints of representation, was born. Every artist from 1863 onwards has, according to this position, been faced with the necessity of, on the one hand, learning the classical methods and requirements of how to make art and, on the other, unlearning all manner of schemas in order that they are able to let their work speak in their own voice.

Maljević has faced her own version of this process, having been trained at the University of Arts Belgrade, which entailed a gruelling seven years of classical instruction, of which the first few years consisted purely of academic and classical arts education – drawing and painting from life, the nude, portraiture, still life and the attendant classical theory. Once this solid traditional foundation had been laid, the fledgling artists were set free to discover for themselves what kind of practitioners they wanted to be. For Maljević, this meant unlearning how to draw – as Picasso famously quipped, “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.”

Maljević speaks of this time as one which provided her with a great wellspring of energy, not so much from the formal education that she received, but from the extraordinary relationships she developed with her peers, with whom she feels she shared a privileged cultural experience. Although, the training itself was classical and rigorous, students at University of Arts Belgrade were encouraged, throughout, to push their own understanding of the subject matter, their own response to the medium, through their images and their mark-making. This stood Maljević in good stead when it came time to “unlearn” and has continued to be the mainstay of her practice.

Although, like all artists, she cites influences and admiration for various artists and art movements, attempting to understand Maljević’s work exclusively through any one particular lens proves a reductive rather than illuminating process. As a painter, her work has undergone transformations over the years, beginning with an excess of impasto mark-making in oil paint, which was perhaps a response to the rigidity of her arts training. In those earlier years, Maljević’s ties to representation were not entirely severed, and her approach was akin to the Expressionists, deftly twisting a form to suit the demands of expression. Over the years, Maljević progressively turned to form exclusively, placing limitations on texture in favour of colour, line and shape. In the way of Formalism, Maljević creates work in which the primary objective is coherence between all the individual elements within a composition – whether they are in conflict or co-existing harmoniously – and therefore its integral logic.

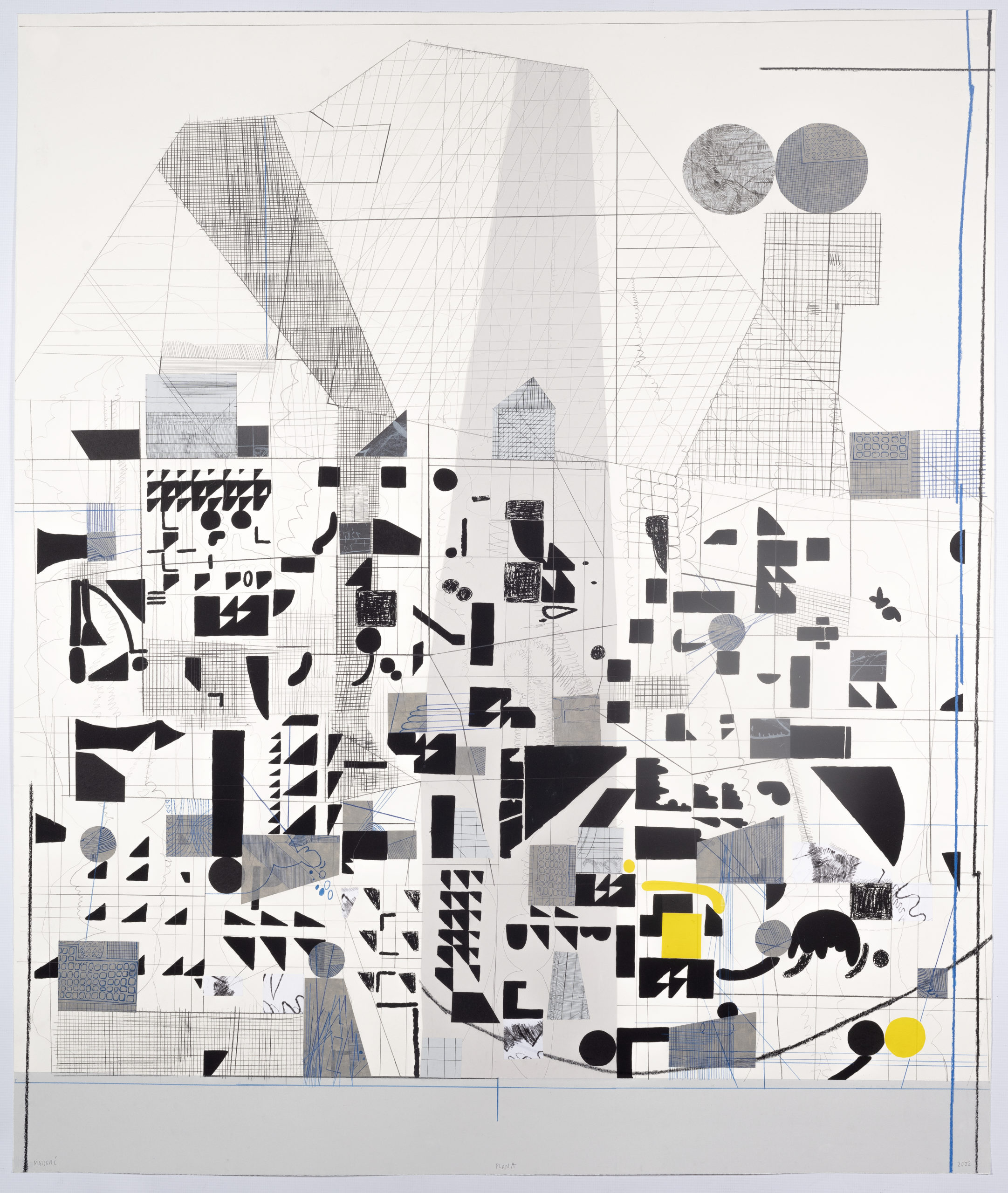

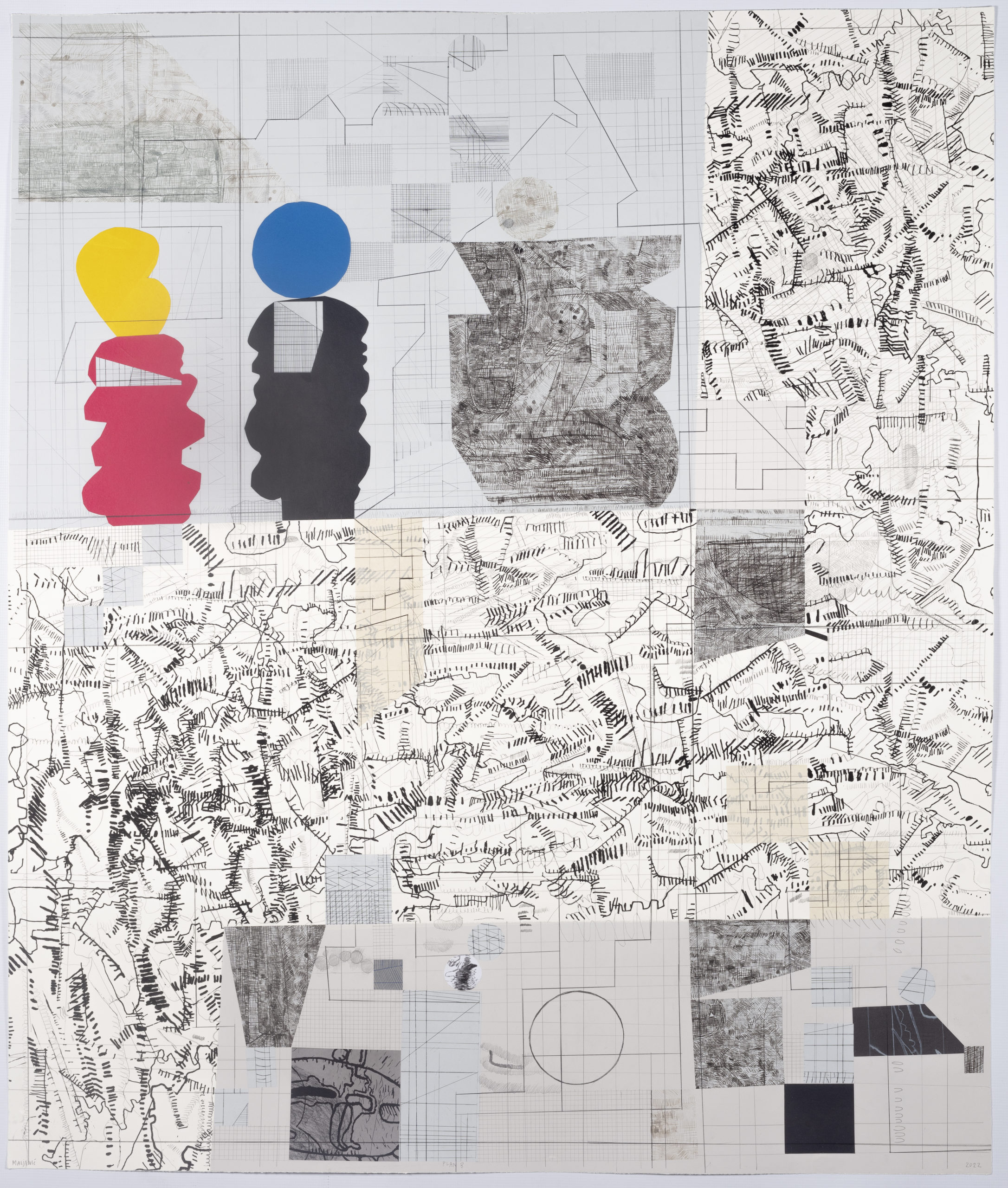

In her latest body of work, Based on a true story, consisting of paintings and large-scale prints produced in collaboration with the David Krut Workshop, Maljević has gone further than ever before in terms of limitation. For an artist whose work has become defined by chock-a-block riotous colour and compositions full-to-bursting with layered formal elements, which exist nonetheless in perfect harmony within the picture plane, Maljević’s new work marks a departure. With a limited palette and a selection of formal elements – specific shapes, lines and marks – that reverberate throughout the body of work, Based on a true story lays bare for the viewer Maljević’s intuitive creative process.

One of the lenses through which Maljević’s work is often understood is articulated well by her synesthetic predecessor, Wassily Kandinsky, an Expressionist who sought to create visual music: “When I combine objects, it is not a play on their meaning and what they should represent, but rather how they clash, feed from each other, create chaos and from that chaos a perfect sound is made, like too many notes that end up forming harmony. You take one out and everything collapses.” In her most recent solo exhibition, The Silence of the Change, which showed at David Krut Projects, New York in 2019, Maljević stressed the point that the marks made in one moment can only be made in that moment, and not the next. This provides another lens through which to view her making process, which is that making abstract art is a way of incubating the state of a nervous system, information and lived experience through line, colour, shape. However, Based on a true story, by virtue of limitation, has offered another route by which one can approach the work.

Around the turn of the millennium, the new materialist view emerged as a field of enquiry. According to Susan Yi Sencindiver, new materialism, as a multidisciplinary philosophical approach, ‘[reworks] notions of matter as a uniform, inert substance or a socially constructed fact [and] foregrounds novel accounts of its agentic thrust, processual nature, formative impetus, and self-organizing capacities, whereby matter as an active force not only sculpted by, but also co-productive in conditioning and enabling social worlds and expression, human life and experience.” In the visual arts, this can be extrapolated as an understanding that each and every medium, tool, colour, technique, shape or line – all the different kinds of matter – that form part of a work of art, have as much agency in the creation of the work as the artist herself. In this new body of work, Maljević reveals her process to be not only underpinned by material as a malleable means through which a number of sensations, positions, and harmonies can be expressed. In these works, Maljević is seen in collaboration with material, with medium, in an intuitive process that defines making not only as an expression of a thought process, but making as a thought process in and of itself.

Roberta Pucci describes the process of being in dialogue with material, in a way that resonates with Maljević’s approach:

“Imagine you are seeing a sheet of paper for the first time in your life: who’s that? The sheet speaks to your eyes, only by its presence: colour, shape, size, location in the space. Maybe it speaks to your nose by its light smell. Then for the first time you take it in your hands. It communicates through its texture, hardness or softness, consistency, humidity, weight, and also with its sounds. If you are curious, with an open mind while observing and touching it, the sheet will reveal to you its possible transformations.” – Dialogue with a sheet of paper

The lines, shapes and forms that reverberate through Maljević’s paintings and prints, as well as the specific, primary colour palette to which Maljević has limited herself, allow an insight into Maljević’s sensitivity to what Pucci has called the “grammar of matter”, the specific characteristics and qualities that define the limits and the potential of every material. Nona Orbach and Lilach Galkin go further in suggesting that, in fact, the material is to be considered a valuable co-collaborator in its own right. To a sensitive practitioner, such as Maljević, who is working in an instinctive fashion, the material, the colour, the medium, has a direct impact on the outcome of the making process.

In the print workshop, Based on a true story has evolved out of milestones achieved in the creation of the previous body of work, The Silence of the Change, which encompassed numerous paper types and weights, diverse colour palettes, multiple intaglio and relief print techniques, experimental wiping and rolling, and a complex, streamlined production process that allowed for the making of work that encapsulated the results of Maljević’s spontaneous decision-making. The prints that form the basis of Based on a true story are the most ambitious to date; layered and complex, incorporating several printmaking processes, and at a massive scale.

Many of the elements stand alone on a smaller scale – plates containing softground or drypoint, screen-printed elements, chine collé and shaped pieces of linoleum – and as a result, these massive prints strike a cohesive corpus, although each one is unique. The works are, for the most part, produced in muted monochrome, with selected primary-coloured elements popping out of the composition, or floating on the surface. In limiting the colour palette, and choosing to re-combine a selection of the same elements in a number of different ways, light is shed on the choreography of the dance Maljević is engaged in with each shape, colour, line or technique.

In the paintings that form a counterpoint to the prints in Based on a true story, Maljević has taken a similar approach in terms of limitation within each composition. For an artist who has, for many years, made a point of allowing formal elements to layer themselves into a painting extemporaneously, working them into a harmonious composition as the painting unfolds, these limitations have required an enormous restraint. The restraint, however, has been generative, in allowing Maljević to pursue each element attentively, within a moderated palette, observing and intuiting what each wants to be. What kind of a life does a line, pattern or shape want to create, when it has the canvas to itself, for a time?

In the process of creating all her work, Maljević is in constant conversation with each component of every composition. In Based on a true story, because the number of elements are consciously limited, each individual component’s voice is heard with exceptional clarity. Maljević, in order to bring these compositions to life, and to a life in their own right, has followed their lead, danced with them, allowed them an agency that only the most perceptive of practitioners are capable of doing. In doing so, Maljević has emphasised that her practice is not limited to the cerebral, and that her making process is underpinned by an understanding that we cannot be separate from the material world. Her work is created by the collaboration between artist and material, in a continuous state of becoming together; a process in which materials, colours and formal elements are considered active protagonists in the making-as-thinking-process, which ultimately results in a mutual transformation that extends the same invitation to the viewer.

Text written by Jacqueline Flint.