ON VIEW:

11 May – 31 August 2013

OPENING RECEPTION:

11 May, 11am with a performance by||Hui !Gaeb di Khoen (Cape Town’s People)

featuring !Hunib !Gû-Kheosab (Bradlox Vans) on vocals & !Nomab Boesman (Colin Meyer) on mouth bow

LECTURE SERIES:

Saturday 3 August – Christopher Swift talks about his “Umlungu” series of etchings.

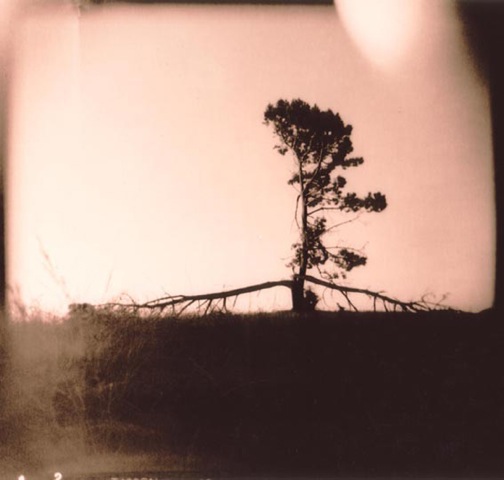

Saturday 17 August – Subtle Agency talks about their “Planting Seeds to Hunt the Wind” collection of photographs.

Saturday 24 August – Francois Krige talks about his life with trees and the Platbos forest in Gansbaai.

Saturday 31 August – Ashraf Jamal talks about trees and weeds, some thoughts on how we live in relation to nature.

View installation images

View images from the opening reception

Read more about the series of lectures

‘Increasingly, I think one of the main functions of concepts is that they give us a good night’s rest. Because what they tell us is that there is a kind of stable, only very slow-changing ground inside the hectic upsets, discontinuities and ruptures of history. Around us, history is constantly breaking in unpredictable ways but we, somehow, go on being the same… That logic of identity is, for good or ill, finished.’[1]

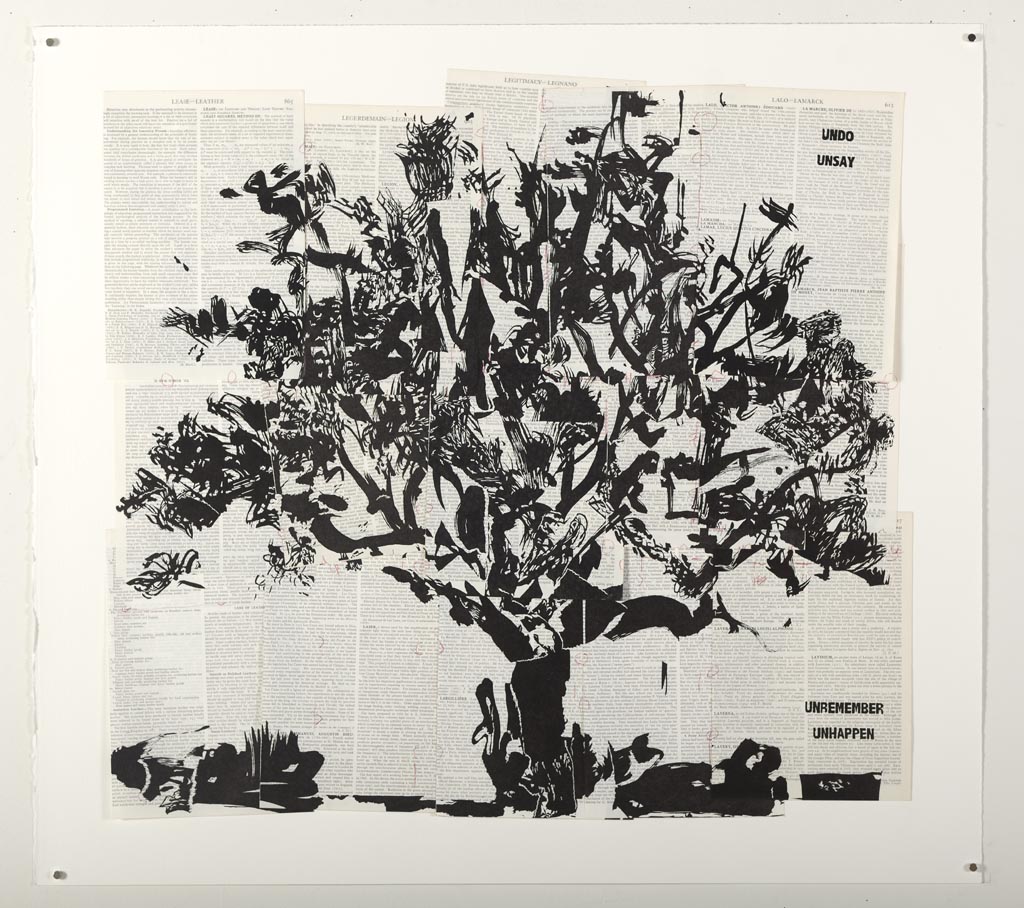

David Krut Projects is pleased to present The Benediction of Shade, a group exhibition featuring a large selection of artists who have engaged with the figure, idea or metaphor of the forest or the tree in different ways and through various media. The methodology of the exhibition is iconic, as opposed to thematic – a curatorial approach that allows for the unpicking and unfolding of the complex connotative potential of a broad and universal signifier. Historically, the forest is a meaningful symbol in many cultures and is currently contentious as a metaphor for sustainable resources, of which generations’ worth of reckless handling threatens our survival as a global community. However, beyond the myriad cultural, historical, social and political readings that can be exposed by this approach, the forest as a receptacle of human creativity and imagination reveals itself as especially significant, in this time of globalisation, when notions of firm and fixed identities become increasingly unstable.

The Tree of Life. The Tree of Knowledge. The Tree of Enlightenment. The Tree of Memory. The Family Tree. The sacred grove. Twin sycamores at the eastern gates of heaven. The Order of the Baobab. Can’t see the forest for the trees. The Brothers Grimm. The heart of another is a dark forest. As the twig is bent, so is the tree inclined. Jungian Archetype: growth towards self-fulfilment. Putting down roots. The hanging tree. Gilgamesh. Daphne and Apollo. Camouflage and the tactical consciousness of war: Agent Orange. Fossil fuel. ‘Waldsterben’ (forest deaths).[2] Oxygen, Carbon Dioxide and Sulphur Oxide. Deforestation. The leafy suburbs. Green Lungs. “Many Greeks would be willing to turn a blind eye to a burning forest if they could build a summer home on the embers.”[3] It’s a jungle out there.

The forest (and the wilderness in general) once represented in Western thought an incredible threatening entity, always encroaching on human settlement – the ‘deep, dark wood’ of so many folk-lores. As European civilisation expanded beyond the capacity of the continent, and yearning and competition for discovery of other geographies to master increased, the landscapes of the discovered continents offered equally terrifying and erotic prospects – the ‘fresh, green breast of the new world’[4] being simultaneously the territory in which the savagery vs. civilisation spectacle of Imperialism played out (something which may perhaps be pre-figured in the ancient Greek myth of Diana and Actaeon).

However one chooses to look at it, forests have reverberated throughout the cultural evolution of mankind. Beyond the capacity of the forest to provide food, shelter, resources for fuel, weaponry and a physical presence around which to build communities, trees have also inevitably become bound up in the symbolic development of culture. Creation myths involving Trees of Life abound in cultures the world over, from the Iroquois of North America to the Shinto of Japan. In an African context, trees have been central to both community building and conflict resolution, holding practical worth as meeting places and mystical value serving purposes in folklore and ritual relating to all aspects of life from birth to death. Each part of a tree holds a different symbolic meaning, representing all members of society.

Today, with rapid global deforestation threatening to accelerate the ecological crisis we face, the large majority of natural forested areas that remain on the planet are institutionally protected as parks or reserves. In Freudian psychology, nature reserves and the domain of fantasy are intricately linked: in the physical world, as places where ‘everything may grow and spread as it pleases, including what is useless and even what is harmful’ despite ‘the inroads of agriculture, traffic or industry threaten[ing] to change…the earth rapidly into something unrecognisable.’[5] In the mental realm, fantasy also serves as such a reserve: imaginative space reclaimed from and protected against the advances of reality. Trees and forests (and our memories of them) can never be apolitical, as sylvan entities defining the limits and nature of the development of our cultures and territories, the margins of our cities and, ultimately, the extravagance of our imaginations.

The exhibition is presented as a dense and overgrown forest of imaginative engagements, a staging that has its own root-lineage in the history of exhibition design – significantly linked to Duchamp’s International Surrealist Exhibition held in Paris in 1938, which ‘responds to the conventional space and experience of an art exhibition, constructing an elaborate answer to both’[6]. This approach becomes particularly compelling at a time when the forest, as a source of wonder and meaning as well as political contention disappears daily from the earth. This transformed imaginative potential that the forest represents becomes increasingly important as we acknowledge the need to discover more cultivating synergetic means.

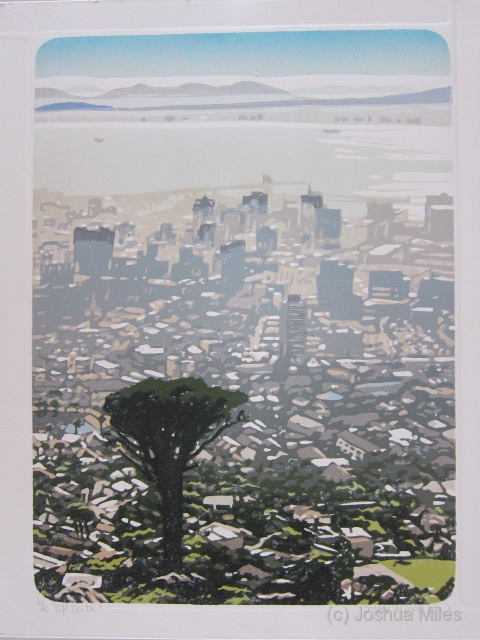

Artists include Ryan Arenson, Beth Armstrong, Lynda Ballen, Emalie Bingham, Stuart Cairns, Vanessa Cowling, Faith47, Justin Fox, Mischa Fritsch, Stephen Hobbs, William Kentridge, Francois Krige, Carla Liesching, Tammy MacKay, Virginia MacKenny, Dillon Marsh, Joshua Miles, Andrzej Nowicki, Dan Perrone, J. H. Pierneef, Gregor Röhrig, Jaco Sieberhagen, Sean Slemon, Sydelle Willow Smith, Subtle Agency, Lyn Smuts, Gary Stephens, Chris Swift, Christof van der Walt and Diane Victor.

In an effort to harness the positive social activism geared towards greening and sustainable living, David Krut Projects has collaborated with Greenpop, a greening project that has an inclusive ethos and runs many activities geared towards activating thinking around sustainability, including tree planting projects, green events, education, social media, voluntourism. There will be an area within the exhibition space dedicated to Greenpop where visitors can sign up either for tree planting projects or “gift” a tree to such. R100 will also be added to the value of each artwork, entitling the buyer to a tree for which they will receive a certificate with GPS co-ordinate details.

A short film by Makhulu Productions (Rowan Pybus, Sydelle Willow Smith and Kyla Herrmannsen) will also be on view in the print room. Makhulu are long-time collaborators with Greenpop and the film, entitled Amazing Grace, was shot in Zambia during Greenpop’s first Trees for Zambia project in 2012. It tells the story of Lloyd Manyana, a Zambian man who stopped his practice of cutting down trees for charcoal and began growing them instead as “payback time to nature”. Lloyd’s micro-nursery is now one of Greenpop’s tree sapling suppliers and partners. The film won the United Nations’ Forum on Forests Short Film Award for the Africa region in April 2013. [click here to watch the film]

[1] Stuart Hall in “Old and New Identities, Old and New Ethnicities” in Culture, Globalization and the World System: Contemporary Conditions for the Representation of Identity, edited by Anthony D. King, 1991.

[2] The progressive death of forests in Central Europe as a result of air pollution. Investigated in Otto Kendler and John L. Innes’ text in progress, to appear in Volume 179 of Environmental Pollution, August 2013.

[3] Costa Kalabokidis, reporting on a series of wildfires that destroyed 25,000 hectares of woodland in the south-west of Greece in 2007.The forestry division has used old Google Earth satellite pictures to protect the land from illegal house-building. Agence France-Presse, May 19, 2009.

[4] F. Scott Fitzgerald, from The Great Gatsby, 1925.

[5] Sigmund Freud in A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis, 1920.

[6] Elena Filipovic in “A Museum That is Not”; e-flux journal, 2009, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/a-museum-that-is-not/