Adrian Fortuin is a Johannesburg-based artist who graduated in 2020 with the Wits Young Artist Award, after receiving the Martienssen Prize in 2019. Since graduating, his practice has shifted from a performative and lens-based approach to a transmedia engagement with painting and drawing. What continues to inform his work is a research-driven, conceptual approach that considers process, along with a myriad of historical, literary and art history sources and socio-political themes.

Adrian is one of three artists we have collaborated with this year in association with FORMS Gallery, founded by Anthea Buys. The results of his short residency in the David Krut Workshop can be viewed in the ‘Parallel Process’ exhibition at our Johannesburg Gallery (142 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parkwood) until 25 June 2022, along with work by FORMS artists Matty Monethi and Khotso Motsoeneng. During his short time in the workshop Adrian produced a large body of work, each piece rich with symbolism.

The themes that interest Adrian in his artistic practice include identity, intersubjectivity (the intersection between people’s cognitive perspectives – the process and product of sharing experiences, knowledge, understandings, and expectations with others), intuition, representation (and the limits thereof) and historical legacies connected to family, community, and society.

Fortuin is influenced by the work of South African artist Tracey Rose, who was his advisor at the Wits School of Arts, Moshekwa Langa, and Japanese photographer Daisuke Yokota, as well as expressionist tendencies in African modernisms and postmodernisms. His paintings are characterised by an obsessive process of revision, in which paintings are sedimented under newer paintings, so that the painted surface becomes an archive of thought and gesture, and a metaphor for the endurance of personal historical traces in the present. His work is strongly informed by the emancipatory potential of abstraction in varying degrees.

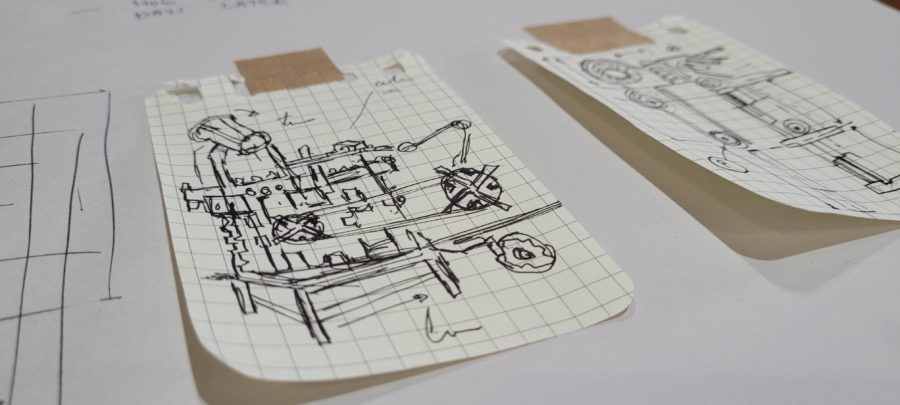

Each unique work on paper that Adrian made in the workshop was prefaced by a preparatory sketch, mapping out the composition, thoughts and influences on the image, and identifying every colour to be used. The titles were also mostly set out in this stage. Despite this apparent rigidity to a pre-formed plan, Adrian worked loosely and was not hesitant to dive right in and see where the process took him.

Printer on the project Sbongiseni Khulu observed that Adrian “made a point of utilising as many printmaking disciplines as possible, as though subconsciously driven by the motifs imbued in his works on a post-colonial South Africa to a ‘born free’ … a desegregation of print with each individual layer.” This ‘desegregation’ refers to Adrian layering different printing techniques on top of one another – drypoint, monotype, embossing and chine colle, or using both oil- and water-based pigments on one sheet. For Khulu, the most defining aspect of Adrian’s practice is the influence of history, which can be observed in both the imagery he uses and his art-making process.

Below we unpack the ideas behind some of his works in the Parallel Process exhibition.

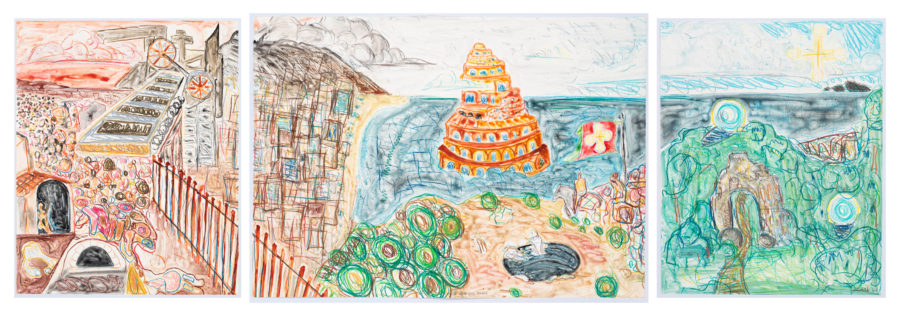

I am the Wound and the Knife

This impressive triptych work was completed in one afternoon at DKW. Referencing three famous pieces of art history from the early 1500s, by Hieronymous Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Adrian also penned an alternate name in his early sketches: ‘Alternative Fictions: Azanian Civil War.’

The final title for Adrian’s work comes from French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire’s (1821-1867) most famous book of lyric poetry titled Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), which expresses the changing nature of beauty in the rapidly industrializing Paris during the mid-19th century. Baudelaire is credited with coining the term modernity (modernité) to designate the fleeting, ephemeral experience of life in an urban metropolis, and the responsibility of artistic expression to capture that experience.

A final reference that Adrian used in the conception of this work is the novel Thriteen Cents by South African author K. Sello Duikar. As a social-political novel, it critiques the ongoing social injustice in post-apartheid South Africa.

Submerged, Suspended, Sublime

This work has two major references. The first is the work of German painter Georg Baselitz, who came to prominence in the 1960s for his figurative, expressive paintings. In an effort to overcome his usual representation and to stress the artifice of painting, Baselitz began painting his subjects upside down. He developed his own, distinct artistic language with influences including Soviet era illustration art, the Mannerist period and African sculptures.

He grew up amongst the suffering and demolition of World War II, and the concept of destruction plays a significant role in his life and work. These biographical circumstances are recurring aspects of his entire oeuvre. In this context, the artist stated in an interview: “I was born into a destroyed order, a destroyed landscape, a destroyed people, a destroyed society. And I didn’t want to reestablish an order: I had seen enough of so-called order. I was forced to question everything, to be ‘naive’, to start again.” By disrupting any given orders and breaking the common conventions of perception, Baselitz has formed his personal circumstances into his guiding artistic principles. To this day, he still inverts all his paintings, which has become the unique and most defining feature of his work.

Baselitz’ work is significant in that it achieves a form of abstraction while maintaining figuration, something which Adrian deals with in his own work.

The second major influence in this work is the Billie Holiday song “Strange Fruit,” the lyrics of which were drawn from a 1937 poem by Abel Meeropol. The song and poem hold a heavy meaning, protesting the lynching of Black Americans, with lyrics in which black victims’ bodies are presented as the “strange fruit” dangling from “Southern trees.”

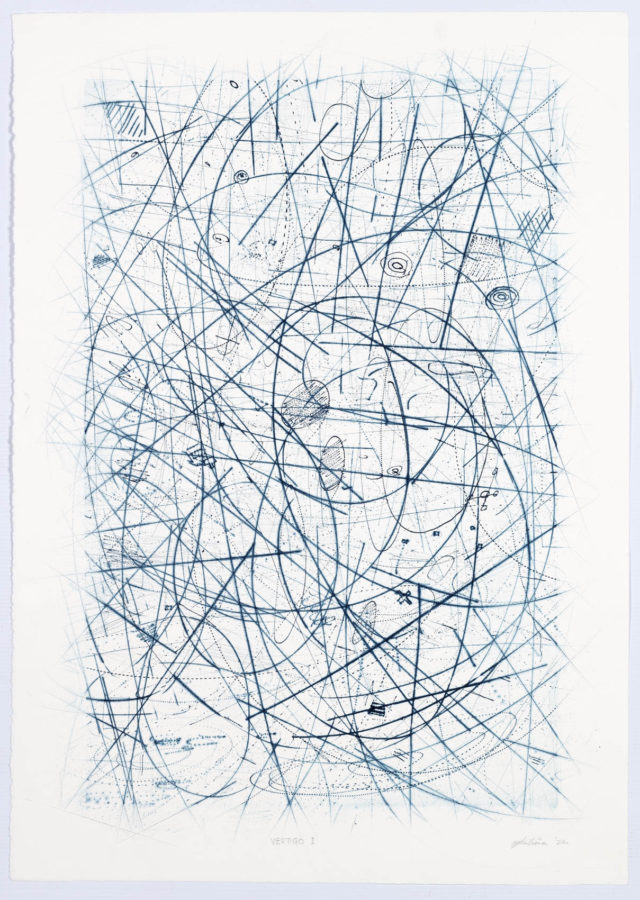

Vertigo II

Penned in Adrian’s notes for this abstract work is reference to Julie Mehretu, the Ethiopian-born artist.

In exploring palimpsests of history, from geological time to a modern day phenomenology of the social, Julie Mehretu’s works engage us in a dynamic visual articulation of contemporary experience, a depiction of social behavior and the psychogeography of space.

With history as a major influencer to his process, Adrian chose the oldest perspex plate in the workshop as a matrix in order to make use of all the accidental and inherited marks on it. He employed different mark-making tools, including a Dremel tool, and chose a specific shade of blue, which echoes the blues that run through much of his other work made during this collaboration.

Eye of Kuruman

This large painting is a mixed media work, with inclusions of beads set into metallic copper pools of paint on the surface. The Eye of Kuruman is the name of a spring in the town of Kuruman in the Northern Cape, South Africa. This area has a fraught history.

Originally, Tswana herders used the spring as a water hole. In 1885, the British classified the area as part of the Crown Colony of British Bechuanaland. This classification of land prohibited the Tswana people from using the stream for any purpose. Access to the valley became segregated by race in the twentieth century under the Union government. A modern irrigation project was operated by the municipality of Kuruman after 1918 and, in 1919 black cultivators were evicted from using water from the eye. However, black people moved 5 miles down the stream to Seodin. The water at the Seodin area had a much weaker stream making irrigation difficult for the Tswana people. The government’s Department of Native Affairs drilled bore holes to assist the black farmers in 1940, however, this was still insufficient to sustain cultivation. In 1962, Apartheid legislation led to the forced removal of black people from Seodin. The ‘whites-only’ irrigation project never commercialized despite state aid.