Text by Christa Swanepoel

Chad Cordeiro is an artist and printmaker currently based in Johannesburg. A body of work titled Notes from the infirmary, was created by Cordeiro as an artist in collaboration with David Krut Workshop (DKW) and Danger Gevaar Ingozi (DGI). Together with Nathaniel Sheppard and Sbongiseni Khulu, Cordeiro co-founded DGI Studio in 2016. These prints were presented in an exhibition at the David Krut Gallery in March of 2022.

In an interview with host of the David Krut Projects Podcast Britt Lawton, Cordeiro gave some enlightening insight into his exhibition and the importance of music in the installation. The following is an excerpt from the interview where Cordeiro speaks on the link between printmaking and music, inter-contextual connections between seemingly disparate archives, and the importance of Cab Calloway and Koko the Ghost in this body of works. Listen to the full interview on the David Krut Podcast here.

“I think a lot of my practice and the artists who I’ve collaborated with as an artist, are interested in how processes of print and processes of duplication and editioning could be interwoven and enveloped into different ways of working: how linocut is similar to records, as an example. Records are cut with a lathe; linocuts are cut with tools. You’re physically carving information into a material.

One is sound. One is image. How do you translate that conceptual process into something that’s more physical?

Printmaking kind of birthed my sound practice in some way… I’d like to think all printers have really amazing music tastes or music collections. I say that as a half joke, but it’s also incredibly true.

It’s very interesting that a lot of printers have really amazing record collections or tape collections or have a really broad sense of music and sense of listening in general. Because technicians, printers, are based in a studio… You have completely different artists coming in all the time to make different work. And those artists, you’re listening to them and what they want to do with the work, how they’re thinking, their practice, what kind of sensibilities they have, you’re also looking in the way they’re producing work. How their hands add to what they’re thinking through conceptually. And we have to be very receptive to the way artists work if we’re working purely as technicians in a collaborative printmaking practice. You have artists coming in and out of the studio constantly. So, it’s a central hub where every artist that comes in will leave a little bit of knowledge behind, generally knowledge of music.

So as a printer, while you’re producing work, you’re constantly collecting information; expanding your ideas and your knowledge of different genres of music.”

When visiting Cordeiro’s March 2022 exhibition, Notes from the infirmary in the checkerboard room at the David Krut Gallery, music can be heard playing. Specifically, samples of jazz music collected and compiled by the artist himself to create a sound installation. The incorporation of sound installation in this exhibition adds multiple conceptual layers to the prints, like a collage element that transcends the traditional boundaries of visual media. Cordeiro motivates the integral role that music plays in his artistic practice:

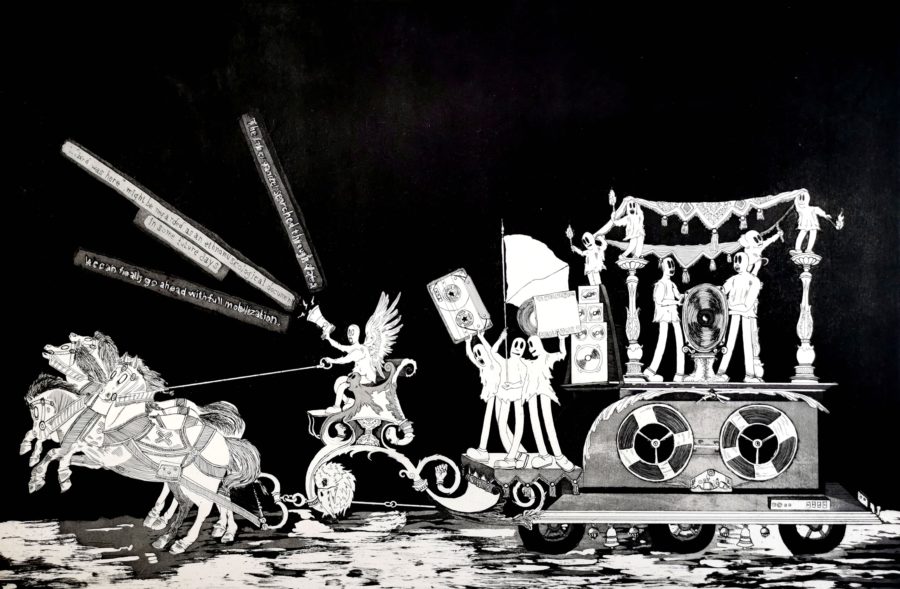

“In my practice I’m interested in personal, collective archives and the haunting that exists within those things and how the archives of music can exist in sound, but also visually. How do we imagine intergenerational and inter-contextual connections between different practices in music and visual arts. I’m interested in, through collage based practice, to kind of make these seemingly abstract connections between kind of disparate archives to see what comes out.

In this exhibition, I’ve done a lot of work connecting to Cab Calloway who was a fifties jazz musician, to problematics of early animation in Disney films to, Frances Bebey, a Cameroonian musicians and poet, to Moondog, who’s also an American musician to Charlie Parker. “

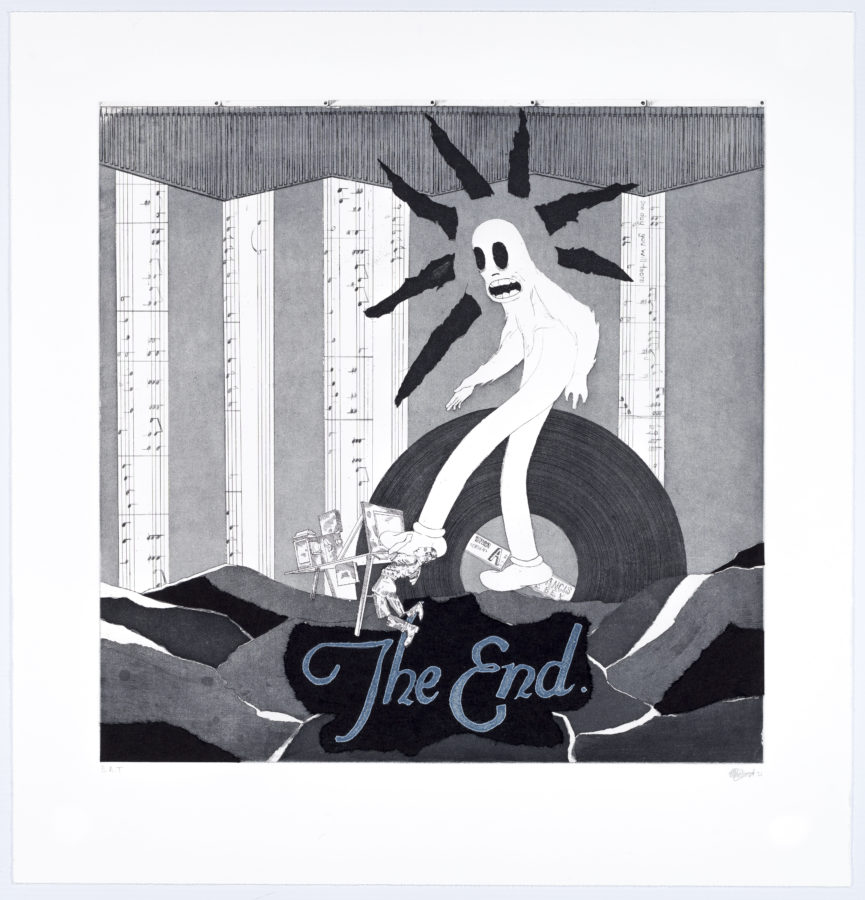

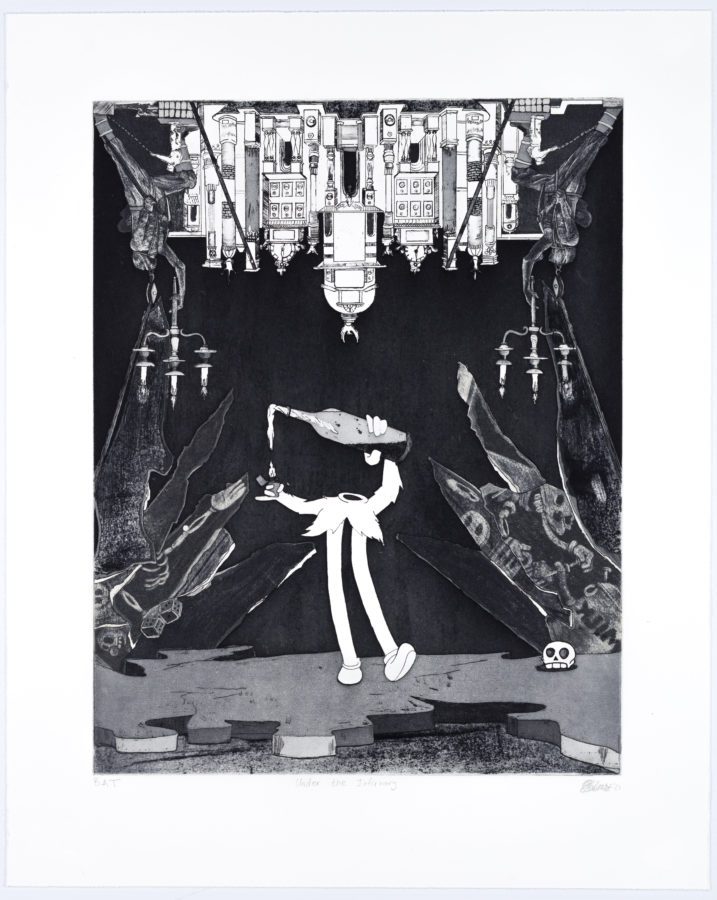

In the interview, Lawton prompts Cordeiro to speak to two of the most prominent pieces so far in the ever-growing body of work: “You had two artworks there, one called The End and the other called Under the infirmary. I wondered if you could maybe give a little bit of insight or background to those two works as well.”

“Yeah. So those are more wonderful examples of this crazy, really fastidious way that I unpack information, I guess. Those two artworks specifically were an exploration into a song called St. James Infirmary. So this song historically has become a kind of open source document, like this really democratized composition. As far as researchers can understand there’s no official proof of the writer, the original kind of composable writer of the song. It’s been covered or reinterpreted in completely different ways by completely different people in completely different genres over 300 times. It has been a song that has been the start of some really big careers over time. Like you have Louis Armstrong doing a really famous cover, you have Cab Callaway doing really amazing, famous cover. You have the White Stripes doing really amazing, famous cover. These are just a handful of the 300 plus times that the song has been used in completely different ways.

The ghost figure is interesting in relation to that song because Cab Calloway’s version of St. James Infirmary existed on the first rotoscope animated film. So rotoscope is this machine that allows an animator to trace film stills directly from life. So from 1933 onwards animations took on a human form. In that film [Betty Boop in Snow White] there’s a character called Koko the Clown who dies and his ghost appears.

So this ghost kind of does a performance and sings St. James Infirmary while he’s trying to bring Snow White back to life. It’s the Dante’s Inferno situation where he goes to the underworld and pulls Snow White from death.”

“The rotoscope, the process of animating the ghost, was using created Cab Calloway’s live performances on stage and his voice. I think that process in itself is really interesting in the way we think about a very direct, very straight forward erasure of certain histories, but also a more subtle conceptual kind of erasure of histories in the way we do things.

Cab Callaway was a black jazz musician in the forties and fifties. This was around the time when black jazz musicians were just starting to be allowed to play in clubs, et cetera. The idea that Cab Calloway’s voice exists in relation to Koko the Ghost is an interesting decision narratively in the film, because you’re committing his movements and his voice to a ghost immediately. This ghost is like alive, but not, so how does that haunting exist in real life?

St. James Infirmary exists through this lense. Many people’s introduction to Cab Calloway’s practices was in this moment in which aesthetically he was reduced a non-living-living entity. This figure of the ghost is a haunting presence that points at and pokes at all these historical issues while being quite loud and inescapable in some ways.”

For more information about Cordeiro’s exhibition Notes from the infirmary, 2022, check out the viewing room on the David Krut Portal here. To read more information about how Cordeiro’s prints are created, click here. To see Cordeiro’s artist profile and some of his other works, check out his page on the David Krut Projects website here.