In this special episode of the David Krut Podcast, David Krut called from the Investec Cape Town Art Fair in February 2022 to host a live interview with Uganda born artist Charlene Kumantale. Charlene was showing her work with AfriArt Gallery owned by Daudi Karungi – long term friend and collaborator of David Krut.

David and Charlene speak about her education in animation, her artistic practice, the use of digital art as a medium, the subject matter of her work, poetry, reading and so much more…

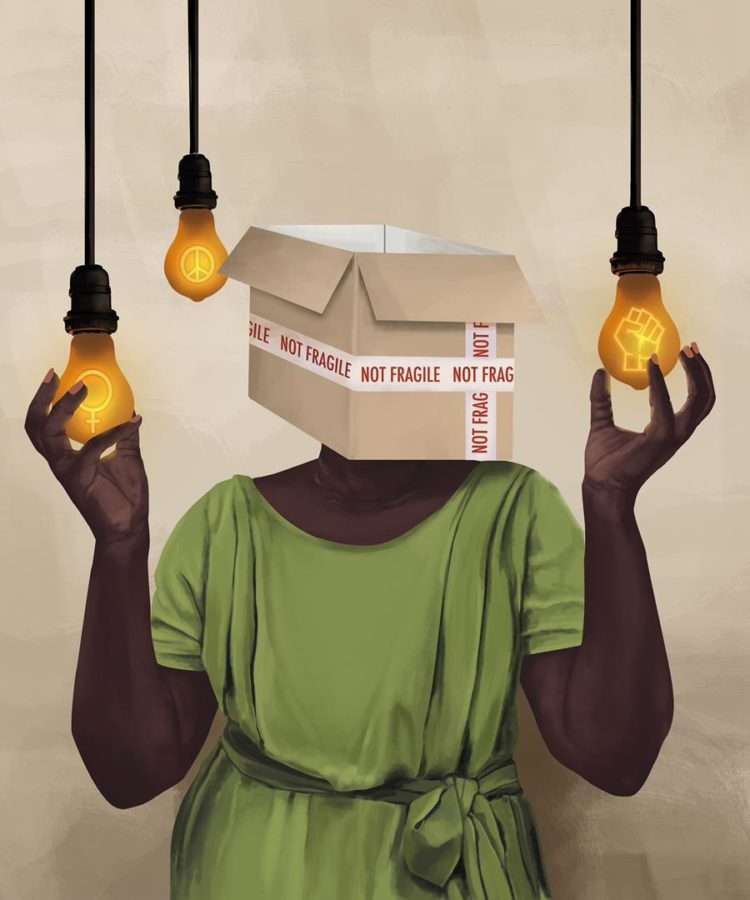

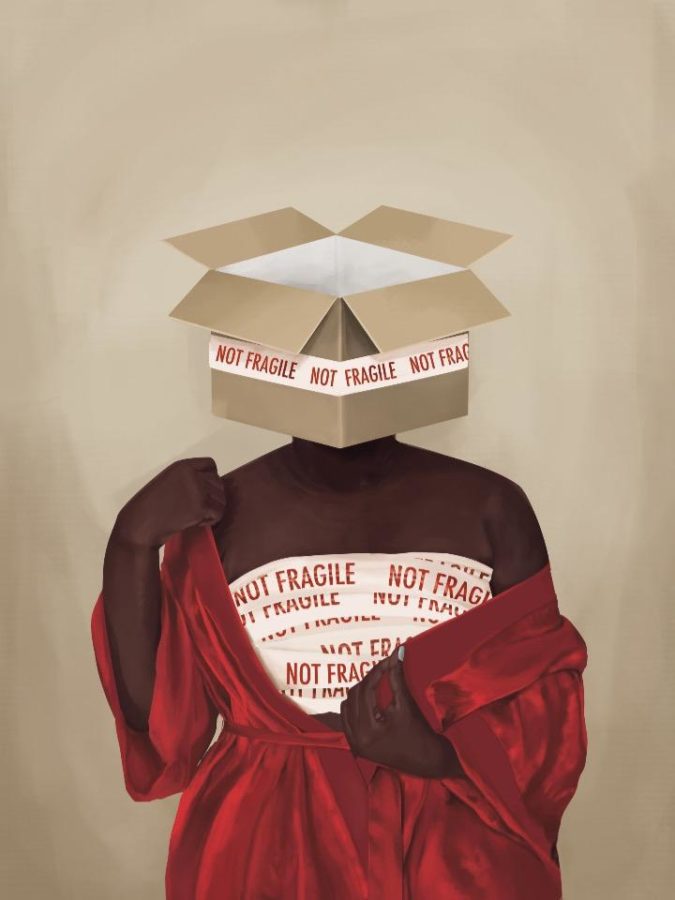

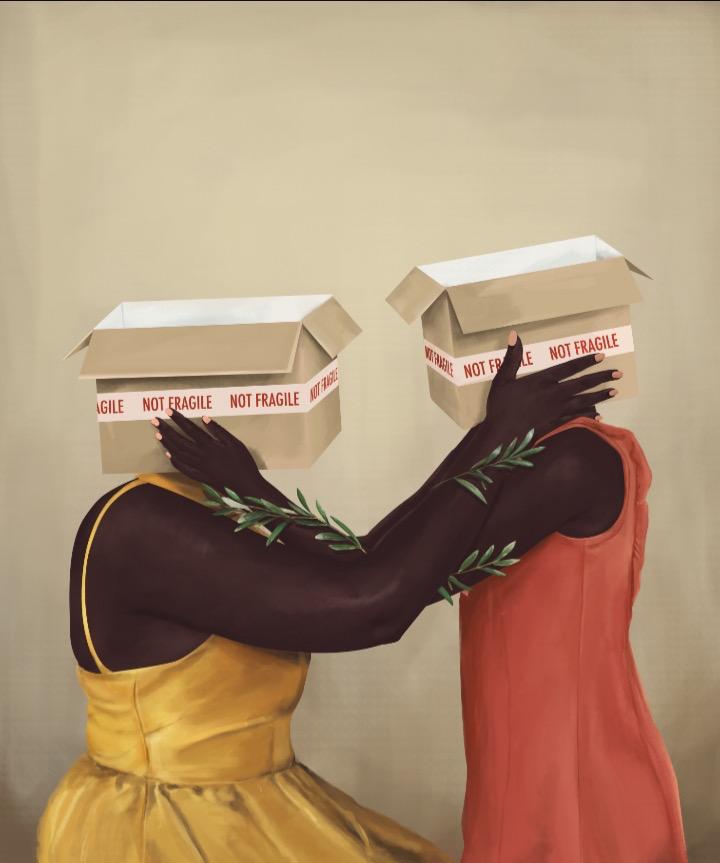

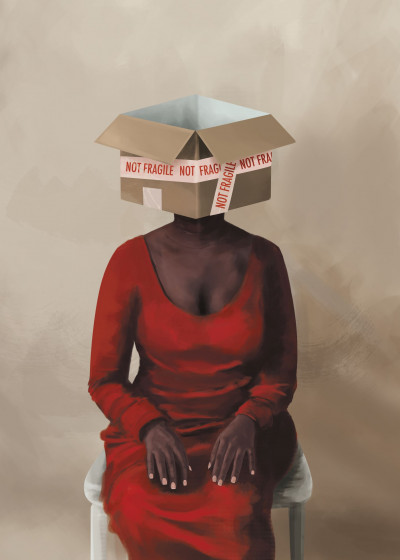

Charlene Komuntale is a digital artist and illustrator based in Kampala, Uganda. She holds a BA in Animation from Limkokwing University, Malaysia. In her recent series-in-progress (some of which were included at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair, 2022) “Not Fragile” and “No Fake News”, Komuntale portrays women – mostly black African women. The subject matter is personal yet presented in a relatable way as inspiration is drawn from her own experiences but also informed by the experiences of other women around her.

Above: Selection of works on show at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair, 2022.

Transcription of the conversation between David Krut and Charlene Komuntale.

Recorded via phone call on 19 February 2022

David Krut: Charlene it’s been so great to meet you here at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair. I am currently standing within one of our favourite galleries from Africa, Daudi Karungi’s AfriARt Gallery. And it’s interesting, your work immediately caught my eye, and something very different to, most of what I’m looking at. And through the conversation with you, sort of now I have a good idea of your background that start six years ago, you were fortunate do an animation course in Malaysia, you returned to Uganda and you were able to survive on commissioned works and now you’ve been making art and that transition is really interesting because in a way you’ve working with photographs two to redo a section. Perhaps you want to explain that process.

Charlene Komuntale: Um, yes, so I work in Adobe Photoshop as my canvas but I take reference images of my sisters and pose them the way I want the painting to turn out. And then I, create these images of women with boxes in their heads, with an unapologetic message that points to their beauty and strength and their unbreakable nature.

So each painting is printed into an edition of three and they are printed on photo rag archival paper with the kinds of inks so they’ll look the same for centuries, kind of like how photographs printed.

DK: So it’s interesting with commission type of work that you’re given, was someone would be sending through a photograph that they wanted to have painted as a portrait, and instead of painting on a canvas you painted on a digital format which you then printed on paper. So the transition from that now, which was commissioned work, to now doing your own artwork and this desire to have ownership is interesting. We’re very familiar with the edition and the archivality and the storyline. And we happen to have someone in our realm at the moment who is working on something similar. Are you drawing on this because of your exposure to advertising and media? How does the confidence of using the work and the creation of an image and using the actual models that come from your imagination—how does that come together?

CK: I find poetry very provoking and I wanted the images to post the poetic, but also I knew the power of words. When someone views the words, they would always remember it. Yes, they say a picture is more than a thousand words, but what about using a bit of both? You know? About the older works, my older series were never printed in archival work, it was just canvas. In Uganda, I didn’t have access to great inks and great paper. So it’s wonderful to see that Cape Town provide that.

DK: So these were actually printed in Cape Town?

CK: Yes, They were printed in Cape Town

DK: So this design, you sort of saying you’ve done eight works in this series and you feel it’s coming to an end?

CK: I’ve done eight successful ones. These showing in Cape Town. I feel like the message has been understood because each painting, the underlying theme with it is that women are not fragile beings. Each painting is breaking a narrative about women. And so I feel like I have exhausted the symbolism, and that’s why I feel like this series is coming to an end and I’d like to explore something new or maybe find a way to make it grow.

Rest is not weakness. Their is great fortitude in choosing to unplug from the rat race .

DK: So this transition you’ve got is challenging in terms of long-term career. Have you thought what it means to become a full-time artist who can create a body of work and can sustain themselves from that and what would be a sort of a journey you think could be developing? Would it be about Africa? Would it be about issues? What takes an interest at this moment, beyond this body of work?

CK: Oh, that’s a very interesting question because I, while I was looking from the outside at artwork, I saw that every artist type of specific stand. And I was worried that I would be stuck in that model of work, and not be able to express myself. And I think digital app allows me to break the bonds of doing the same thing for centuries. Because, as an artist, I feel like there should be a way for you to express yourself continuously without only creating a piece of work that has been successful. So I’m trusting in my creativity to push me forward with storytelling and texts. And maybe in the next series it can be a newspaper.

DK: Do you ever do direct work when you’re drawing or is it just the base, you and the monitor and your iPad?

CK: Um, my earlier works, uh, was a lot of drawing and pencil. Um, but I found digital gave me the liberty to play around layers because you can always switch off a layer, see if it works if it doesn’t, bring it back in. I do find it soothing to work with traditional, tangible mediums and see how I can play with them so that I can create that same effect in a digital platform. It’s nice to touch the oil and see, oh okay, so this is how thick it can create that reality, that reflection

DK: Are these sort of materials easily available to you in Kampala?

CK: The really nice ones– not so much, but you work with what you have.

DK: In terms of personal circumstances, the road of becoming an artist is a bit tough. Do you have a support system? Are you living with family? How does it work at the beginning of a journey, the big leap?

CK: Yeah, so thankfully I have a really good support system. When I was growing up, my dad always loved the works I’d create. I’d recreate covers of artists’ albums and he say, ‘this is so good.’ I actually went and studied Spanish as an extra-curricular activity because I thought I was going to go to Spain and do art. My mother would say, ‘Why are you destroying the books that I give you? Stop drawing commentary and all that.’ Fortunately, she jumped on board and made for me an art studio and I got to be on my own and create my own works. She pushed me to find a way to make art work. And that’s why I went away to do animation—I didn’t think that I could just be a fine artist. No one was buying art. We had this stereotypical art that all of us in Uganda know: the zebra, and lions. Animation felt like it had more prospects for me. But an aspect of animation is what I mean, which is storytelling and concept development. And that shows in my work– the will to tell a story. Even when the viewer, even if I’m not there in the room, to explain to the viewer what they’re seeing. And that’s essentially what animators do.

DK: And do you read extensively, books or do you put the words together yourself from your own range of words or your own experiences?

CK: Uh, yes, a lot of experiences, but sometimes I get these—words come to like truth. But, truth is a very broad word, like truth is relative to many people. So I had to find a way to make sense to the everyday person. And I think discussing posts with narratives in my work makes it more understandable and not forcing an idea on someone about yes, subjective feedback.

DK: What are you thinking you might make or draw from your own life?

CK: Oh most of the work. Actually the very first painting is of a lady in a red dress with her hands on her lap. And I remember having a conversation with my sister and talking about how we have been put into this narrative, that if you have perfectly manicured hands, that you cannot amount to anything, your hands should be, you know, to show what you have done when you’re able to do so.

She has manicured nails for juxtaposition. Red Dress debunks the idea that a woman’s worth is defined by what she does and how she presents her self.

She can’t cook. She can’t do much housework. So at work, educated people tell her then, ‘I can’t marry you. You don’t work.’ You know, but I wanted to show in that painting and capture the beauty in her still moment of how manicured perfect nails and say she’s not a fragile being even if you have a subjective feeling about her. So I have these conversations with the women around me about intimacy and vulnerability about faith. Because I am a Christian, but a feminist. What does that mean? Many people think, okay, you’re a Christian, but the background of your faith is patriarchal. So how are you a feminist? So I did discuss that people in my work.

DK: Just coming back actually, the hands, do they feature a lot in your work? Because a lot of your works decapitate the figure.

CK: True! I think what’s permanent is the way they are posed. And also hands do work in some of the paintings. In one they (the figures) touch each other’s boxes and it had olive branches moving around, showing that when she touches your box, really this shows that I can acknowledge your state of mind. So it depends because every drawing is intentional. Every object in the painting is symbolic. Every movement is symbolic. So touch isn’t just because it works.

DK: And the idea of the box as the head, where did that come through?

CK: I think, even in my early works I’d have some of the faces of my subjects disappear. So I liked the idea of covering with the boxes. I think also because, the monotony of doing portraits bored me, like I cannot draw a face again, I have to find a new way of doing it. So I had to think outside the box and I took it literally.

DK: Oh, what a great story! Any thoughts about your residence with Daudi?

CK: Ahh, so I think that there was a phenomenal way that he brought me. I entered an art competition, my very first. And I almost didn’t submit. I did not win, I was long listed, I wasn’t even in the top 3. And Daudi’s scout went through that list and found a painting I’ve done of this woman, her face was covered with a cloth. And there were these birds with pearls. And it was talking about this nation of Uganda and how we are other covered to our beads, because I think one the explorers said that ‘Uganda is the pearl of Africa.’ So, it had a lot of symbolism. But he thought it was a painting. And he thought it was a painting. Because the first day I showed up, he said, ‘This is not a painting? This is digital? I’m very sceptical about your art.’ But he was like, ‘there was something about your work that drew me in, because your storytelling is very powerful.’ And those three months were exceptional. It allowed me to remove myself from the Cushite mission which boxed me in for so long. And he said, ‘don’t go back to that mission. You can’t get out of that box and enter it again. So, stop all you’re doing and focus on this.’ And I actually took it literally. It’s incredible.

DK: What a great story. Well, a big thanks again to Daudi at the art gallery and Charlene from Kampala. I’m sure you’re going to have a great career and I hoping we can find a way to show your work as well.

CK: Thank you.