Stephen Hobbs

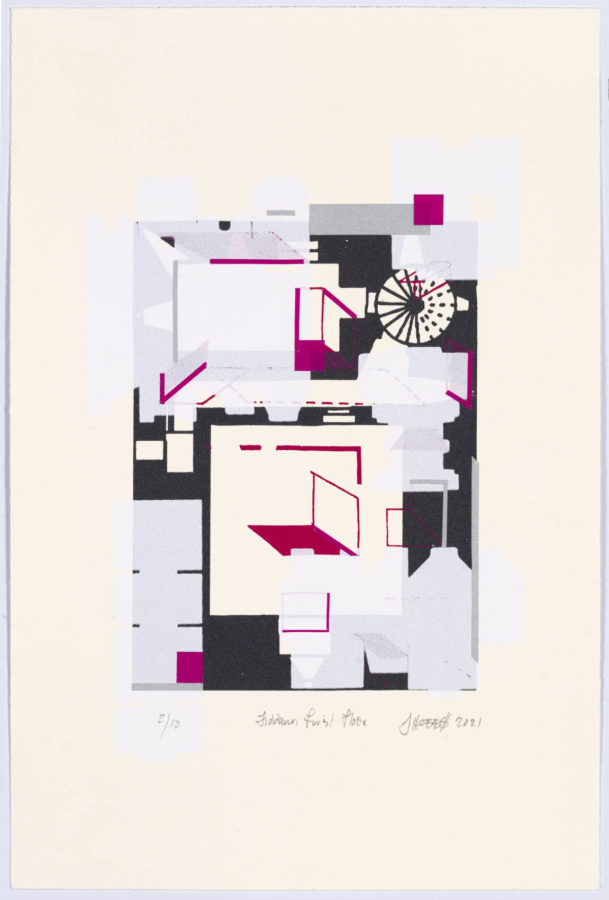

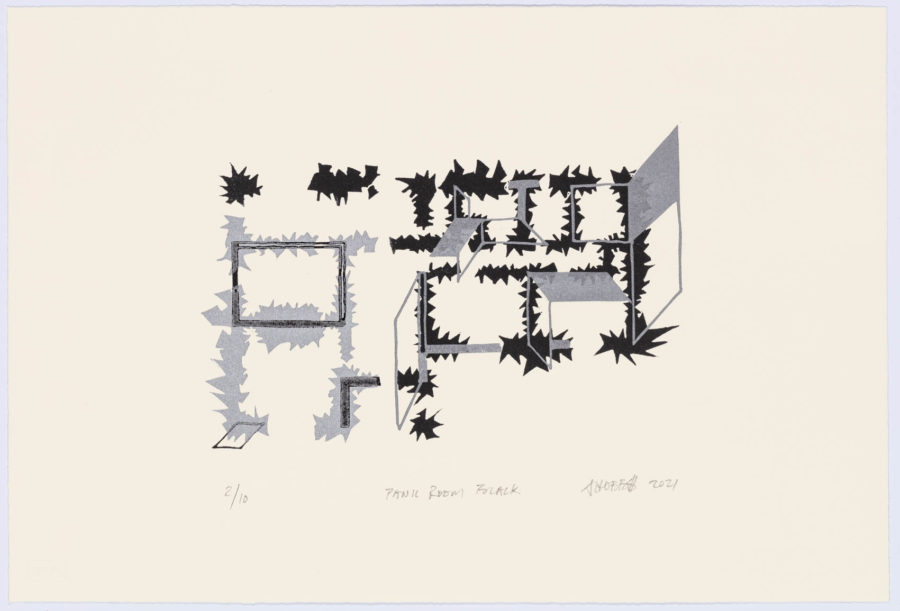

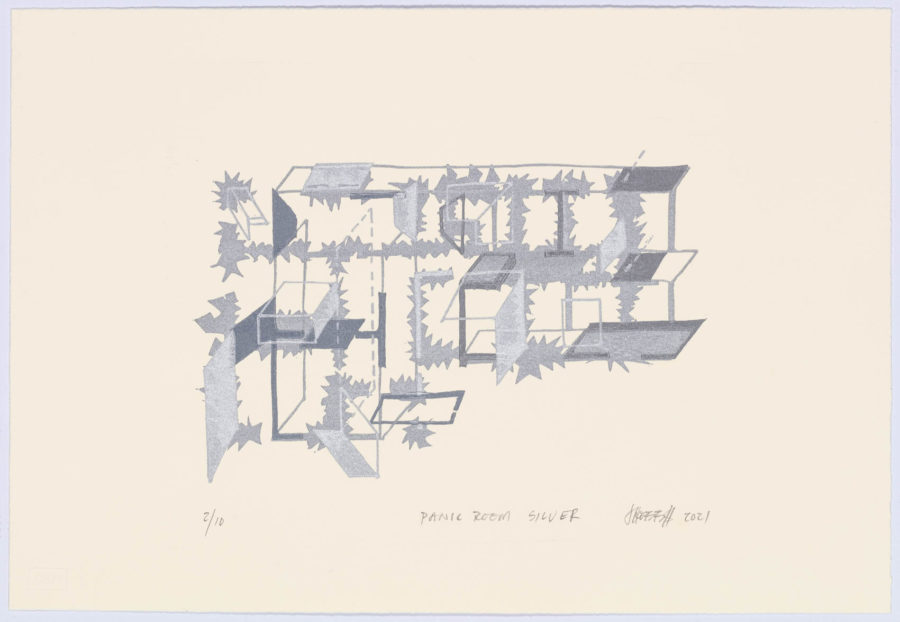

Linocut, silkscreen, and tape

37 x 25 cm

Artist Stephen Hobbs’ practice is significantly informed by architecture, the built environment and the social layer upon it. The essential ideas within his work always seem to be underpinned by scaffolding or engineered structures of some kind, usually with the fastidiousness of precise angles. Along with this structural thread, those familiar with his work will know that he also deals with concepts of war and defense, as well as anatomy and the body. Hobbs is able to fuse these ideas in profound ways, seamlessly making connections related to personal and public histories.

His latest, growing body of work has come out of such recent histories, and draws on all three of the core fields that have interested him for much of his career. In 2019 Hobbs and his family uprooted and moved to Glenville, a rural village in County Cork, in the Republic of Ireland, 4 months before the Covid-19 pandemic hit. The resulting experience of trying to set up camp amidst strict lockdown measures in an unfamiliar environment, and the effect of this on the personal psyche and family relationships, informs current developments at his studio in Maboneng, Johannesburg.

Soon to be opened to the public is a large-scale installation, a studio-turned-immersive exhibition, which charts Hobbs’ and his family’s experience in Ireland and the history of land-use relations in the country. Imbedded in this is a distinct allusion to conflict and warfare, referencing Ireland’s war-torn history, the architecture of wartime structures and fortified domestic spaces (particularly pertinent when viewed from the “other” side of a global pandemic), and measures of safety and caution, through a palette borrowed from high visibility safetyware.

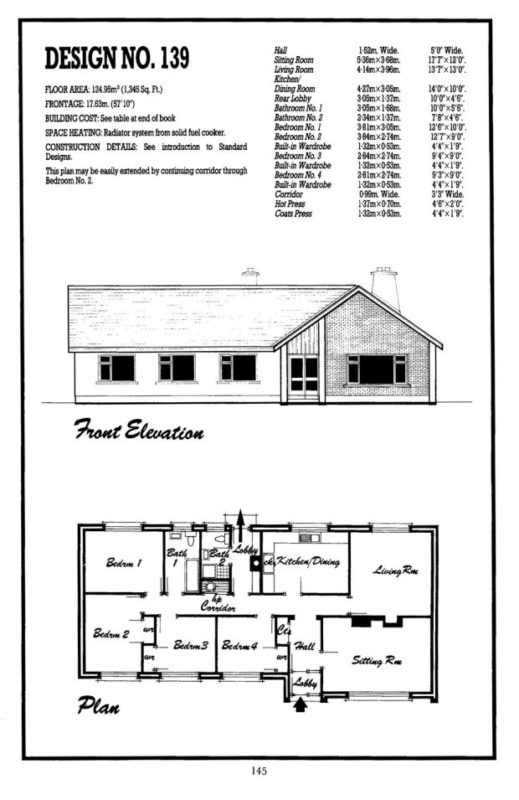

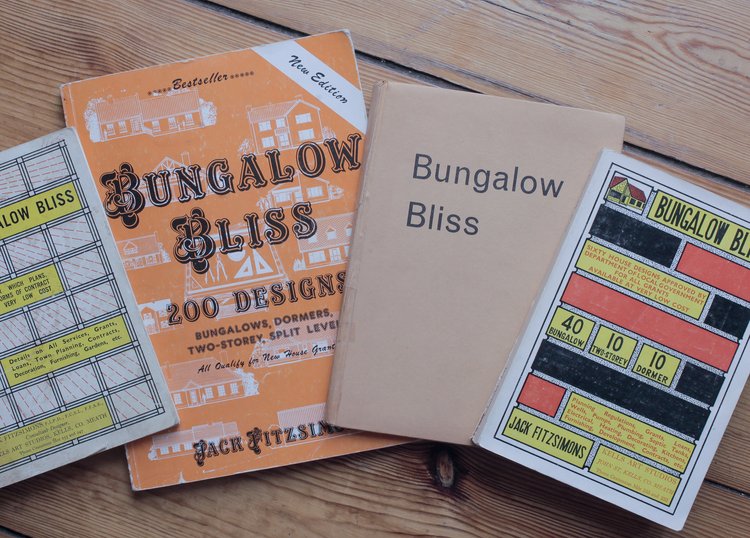

Hobbs’ reality in Ireland in 2019 soon became confined to his family’s new home – a housing typology developed during a major housing revolution in rural Ireland in the 1970’s that was inspired by Jack Fitzsimons’ publication Bungalow Bliss. This ‘how to,’ step-by-step guide changed the face of Irish building and living. Before this, options for housing in rural Ireland were limited to inheritance, getting on the housing list or emigrating. This question of access in terms of the built environment has long interested Hobbs, often with regards to South African history and the city of Johannesburg.

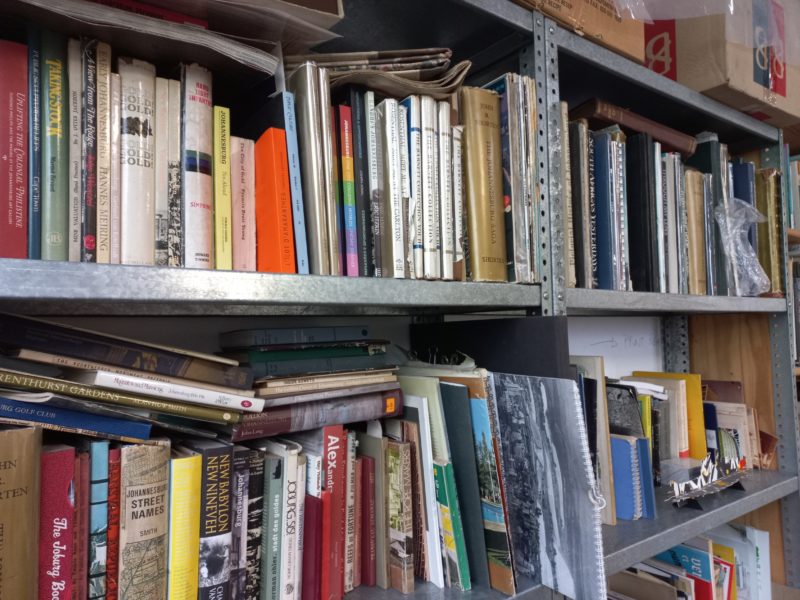

While his current work is never far from societal histories and geographies, it is far more domestic and personal, referencing the very walls of his family’s house and inner feelings of confinement and panic during the strangest time to date of the 21st century. Apart from the installation taking shape at his studio, so far the body of work consists of editioned prints, initiated at last year’s Turbine Art Fair during his Woodview Residency, and what are known as the ‘box works.’

The box works began in Ireland during the 2020 lockdown. In the absence of readily accessible art materials, Hobbs turned to the flurry of cardboard box packaging coming from online purchases. In their open, die-cut form, the boxes echoed floor plans of an imaginary kind. Enamoured with the domestic scale and functional features of the bungalow they moved into, the boxes in their flat-form became the substrate for a range of drawings, executed for the most part with reflective tape from the local hardware store.

These works have evolved with the assistance of the printers of the David Krut Workshop to include silkscreened elements, referencing, amongst other things, the checkerboard tiled floor of the bungalow’s entrance hall, medieval castle floorplans, and a curious pixelated tree from a map of the Glenville area which delighted Hobbs in its incongruent modernity. The boxes speak to many things, such as our e-commerce world of instant gratification and increasing impersonality, but also to notions of confinement, the ‘flat-pack’ houses detailed in Bungalow Bliss, and the boxing up of lives during continuous moves.

Written by Melissa Waters