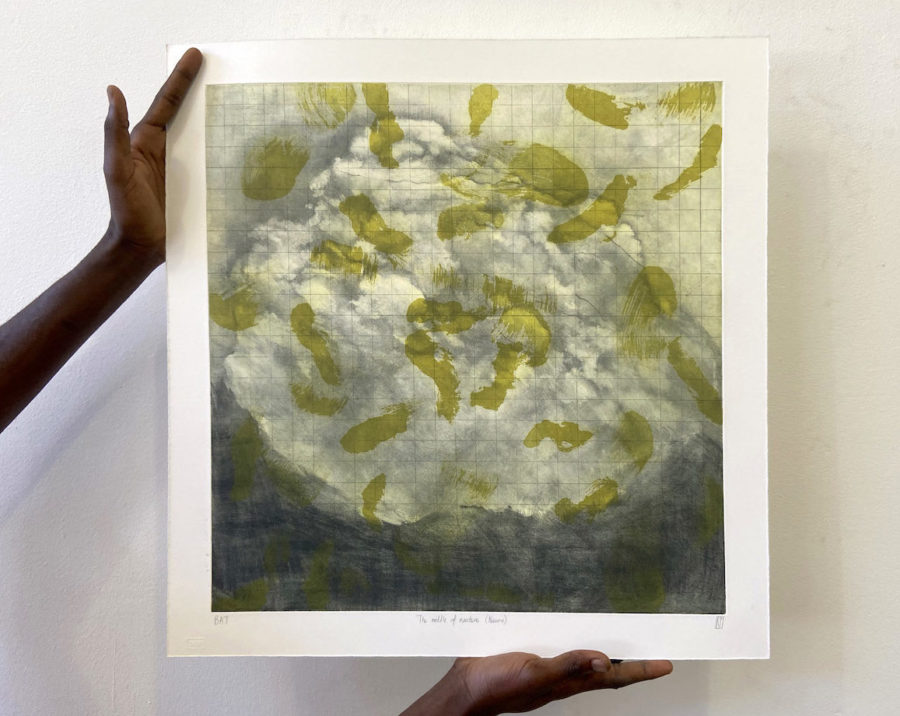

The Middle of Nowhere (Nauru), 2016

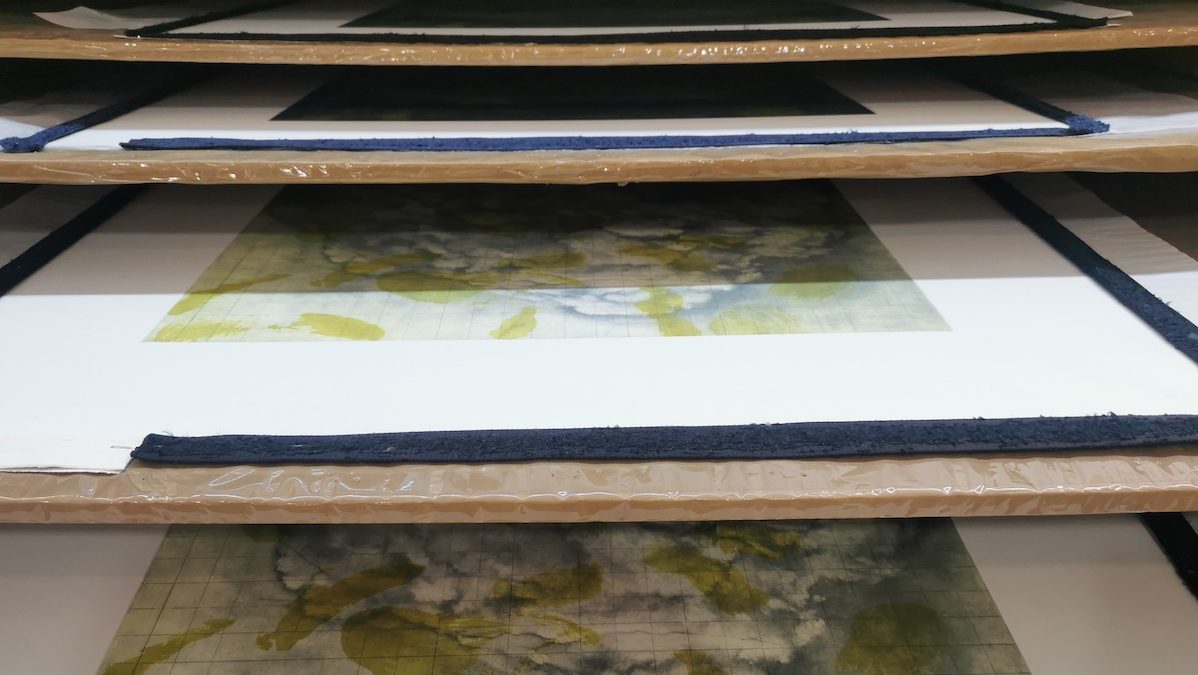

For the month of September we are highlighting Robyn Penn’s intaglio print, The Middle of Nowhere (Nauru), 2016. This print was made in 2015 with Master Printer Jillian Ross and printers Neo Mahlasela and Kim-Lee Loggenberg. It was the last work created in a series of prints made with the workshop, which began in 2015 with a number of monotypes, smaller mezzotints (Nine Views of a Cloud) and large etchings – Cloud of Unknowing, consisting of 5 works and The Map is not the Territory consisting of 3 works. At the time a number of prints in the edition were printed, with the balance of the edition being completed this year.

Penn’s constant return to similar subject matter – in this case, clouds – is significant to her practice, and is summed up beautifully in the following text, written by Richard Penn for Echo in 2013:

“Something interesting happens to our experience of time when we look at the sky or at the ocean. At a glance they are static and unchanging but after an interval they are transformed entirely. It is this interval that is one of the main foci of Penn’s work that she explores through repainting the same cloud in similar as well as different scales and techniques. But it is also a period that is elusive and resists pinning down. Through re-painting and repetition, the interval in Penn’s work starts to describe the kind of minute and slow changes in nature that hold us in rapt astonishment when speeded up in a time lapse sequence. Such a focus on these tiny increments of transformation can be seen as a rejection of the narrative of the transformation (this changes into that) in favour of the process of alteration itself. In our own every day experience of time, cloud and sea change slowly but instead of speeding up time to make the changes clearer as in a time lapse movie, Penn calls a halt and situates herself in the space between transformations. In this liminal space the addition of only slightly differing images has the opposite effect and works to expand and slow down time.

To paint an echo, to slow the clouds, Penn’s work can equally be seen as an attempt to hold back chaos and entropy as the careful study and immersion in the natural processes of transformation and dissolution.”

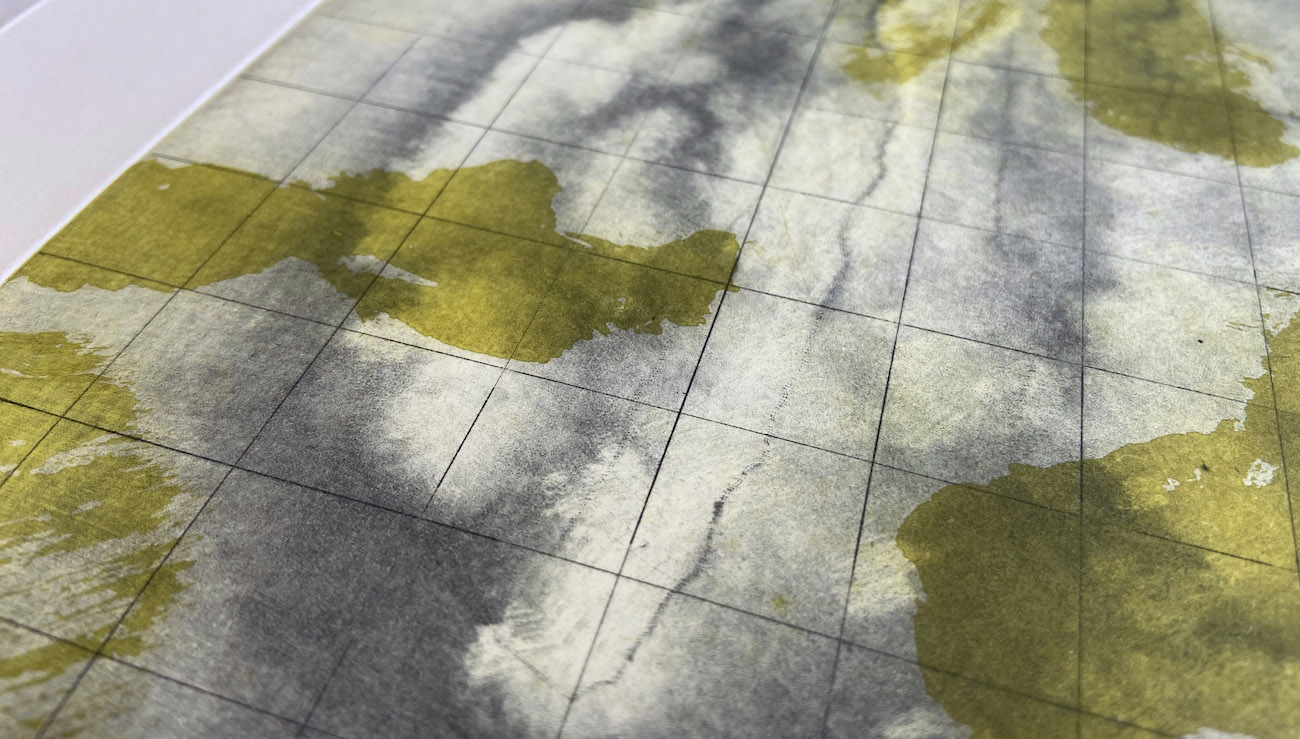

The Middle of Nowhere (Nauru) is a large two-plate (or layered) print. The first plate was made using the technique of mezzotint and hardground etching. Mezzotint is a technique in which the entire sheet of copper is ‘rocked’ with a sharp bladed tool to create a solid velvety dark tone. The image is then worked into the plate reductively with a burnishing tool, flattening down the tone to create lighter areas. After completing the image of the cloud Penn then used a tool to draw a grid into hardground. Making a mezzotint on this scale is challenging and the image was resolved with the lines and a second plate.

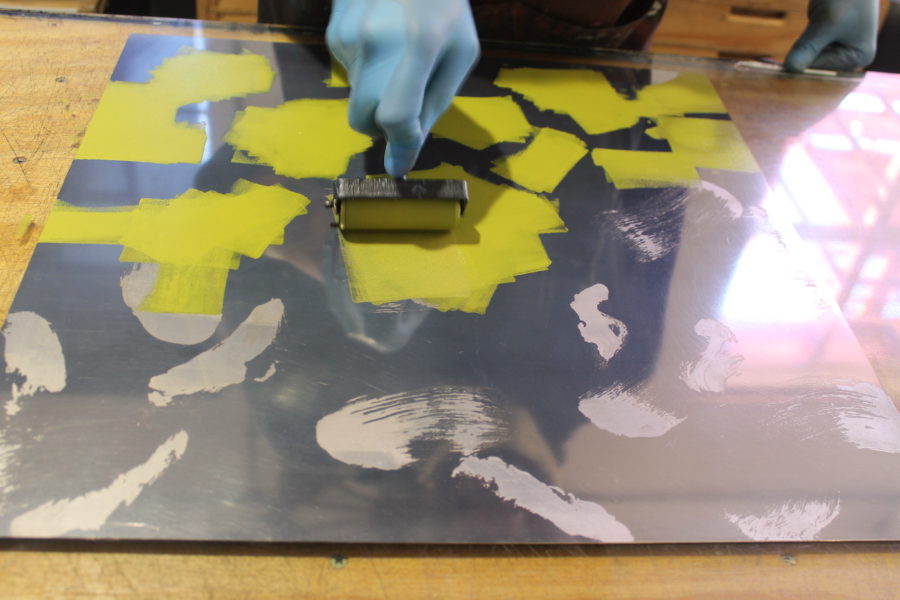

The second plate was made using the technique of sugarlift aquatint. The artist applied thick gestural brushstrokes using condensed milk onto a copper plate. A layer of ground is then painted over the entire plate to protect the exposed copper from etching. The plate is then submerged in warm water, which removes the condensed milk, leaving areas of the copper exposed and ready for aquatint application to etch a solid tone.

Read David Krut Workshop’s (DKW) conversation with Robyn Penn (RP) to learn more about how and why the work was made.

David Krut Workshop (DKW): Why did you add the grid into the mezzotint plate?

Robyn Penn (RP): In this mezzotint and sugarlift etching I hoped to make an image that was dreamy and beautiful and recalled old maps. It is titled after the small, potato-shaped Micronesian island, which lies in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Australia, in ‘the middle of nowhere’. The addition of the etched grid hopefully shifts the viewers perspective from seeing the cloud to seeing the mapped island.

DKW: Why did you add the second plate (the plate with the brushstrokes) as opposed to leaving the image of just the grid and cloud?

RP: The making of this etching was an incredible, though long and arduous process. This particular piece of copper was somehow ‘hard’ and seemed ‘thin’, unrelenting to the rocking and not easily yielding the rich velvety black one hopes for in a mezzotint. The burnishing was also onerous, a real labour of love. I worked on the cloud image for almost a year and just as I had it at a point that I was pleased with the image, there was a disaster in the print workshop. The plate is steel-faced to protect the copper in printing. A mezzotint has to be printed several times during the making for the artist to see the image, as it is hard to see on the surface of the plate. After ‘proofing’ the steel-facing is removed with a nitric acid solution to reveal the copper below. An assistant printmaker, confused pure nitric for the diluted nitric and when it was poured on the plate the image was obliterated! Fortunately, no one was hurt. I was left with a plate that had a ghost of the previous image, not intricate enough to stand alone, but there was something very enticing about it. I set to work on re-rocking and burnishing the copper again. This time my marks were less refined and more gestural. At this point I decided to etch a grid over the cloud and on a second plate made a sugarlift etching with gestural brush marks that, together with the re-worked cloud, brought the complexity with its ‘history’ and imperfections that I needed in the image.

Printer Kim-Lee Loggenberg steel facing one of the copper plates.

Test prints of the plates are done in different colours.

DKW: Are the brushstrokes on the second plate random or are they considered? Do they correspond with areas in the “background” (cloud) plate?

RP: The brushstrokes are carefully considered, random marks! Their placement is balanced compositionally to add to and not detract from the cloud.

DKW: What made you decide on the colour of the brushstrokes plate? (Acid yellow-green)

RP: For millions of years Nauru was home to bat colonies and their guano made Nauru’s soil and rock phosphate-rich. The island was inhabited 3000 years ago and the indigenous population enjoyed a prosperous existence. In 1900 a European visitor to Nauru realised the value of the phosphate-rich land and mining began in 1907. The phosphate was shipped to Australia for use in fertilisers. In the late 19th century Nauru was annexed by Germany. After World War I the UK, New Zealand and Australia administered Nauru. In World War II the Japanese occupied it. After WWII the country entered into UN trusteeship and in 1968 Nauru gained its independence. However, the mining was so extreme that by the 1980s it had devastated about 80% of Nauru’s land area and about 40% of marine life. A significant proportion of Nauru’s population was evacuated and integrated into Australia. Today Nauru’s outer rim is still beautiful, clad with palm trees and beaches, which conceal the inner devastation of the strip-mined island. The gold green I used in the brushstrokes had this story in mind. That is, one of wealth, exploitation, fertilisers, growth and devastation.

DKW: Are there any anecdotes or memories linked to the making of this image in terms of collaborating in the workshop?

RP: The mezzotint was mostly worked on in my home studio and then brought in to DKW to proof and print. I remember William Kentridge coming into the workshop after the nitric acid explosion. He must have noticed that I was distracted. When I relayed the accident to him, he replied with something like, ‘That’s printmaking, just go with it!’ So, with renewed optimism I set to work with Jill Ross, whom I thoroughly enjoyed working with, and we toiled together on rescuing months of elbow grease and passion.

Robyn Penn, Master Printer JiIlian Ross and assistants Neo Mahlesela and Martin Motha looking at Penn’s smaller series of mezzotint prints.

Master Printer JiIlian Ross printing one of Penn’s etching plates.

To see more of Robyn Penn’s work visit her artist profile here.