Written by Sbongiseni Khulu

In recent months a great deal of change has come about in the world as a result of a global pandemic, to which even the constant illusion of time has fallen prey, becoming fickle as a result. It’s in moments like these that Einstein’s rejection of time as a concept with distinctions between past, present and future echoes true. Although I can’t say for sure what day of the week it is, I can still say I know a fair amount about the arts and in that I find some solace. On that note, I’d like to share my experience of a time before global crisis, a time lending itself to the artistic and musical expressions of composer João Renato Orecchia Zúñiga, the woodcuts that came of these expressions and the solo exhibition, Instruction, that resulted in 2019.

(Editions of 3)

Right image: On the left Master Printer Jillian Ross, on the right artist and composer João Renato Orecchia Zúñiga

Today, printmaking accounts to nine techniques, each uniquely dedicated to the transfer of images from one surface to another in a particular way. Woodcut is amongst the oldest printmaking techniques and its use can be traced back to as early as the 5th century in China. While woodcut first gained prominence through practical uses, it subsequently became recognised as an artistic medium thanks to the widespread development of paper.

In 2007, years before Orecchia arrived at the point of making woodcuts, he had his first solo exhibition with David Krut Projects (DKP), which comprised a display of sonic experiments. In 2010 his connection with DKP strengthened through collaboration with Master Printer Jillian Ross and designer Lisa Jaffe. Their ensemble showcased a monotype-based performance of printed fabrics at Arts on Main, Johannesburg, with Orecchia’s contribution serving as an enveloping sound performance. The showcase was later adapted for an exhibit at the Joburg Art Fair in 2011 for Marie Claire magazine.

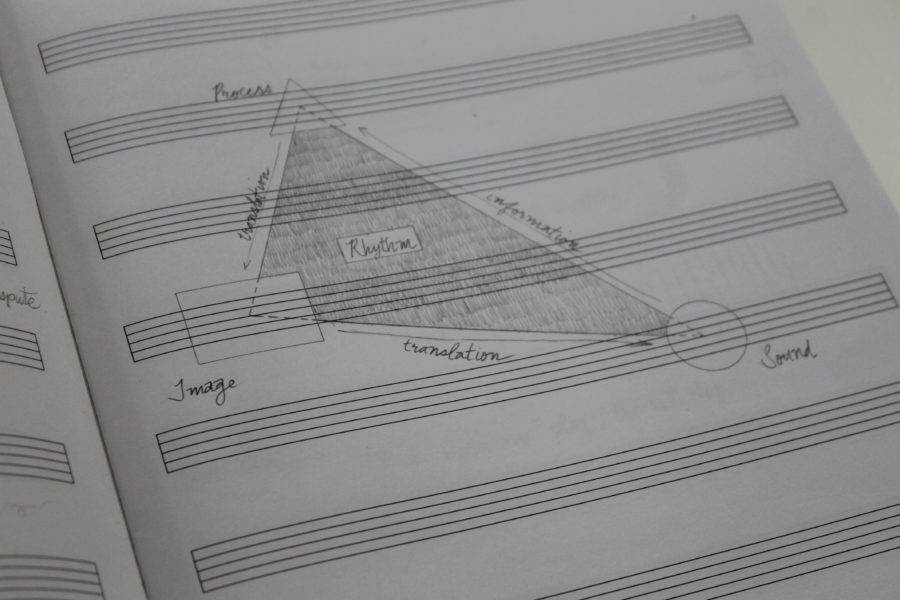

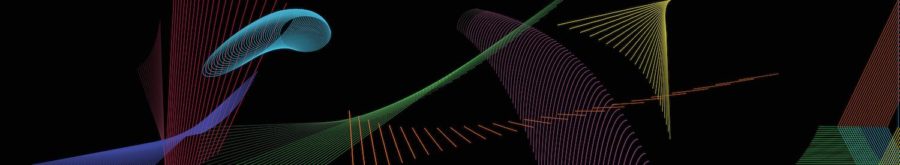

Orecchia was later invited to collaborate with The Centre for the Less Good Idea for their first season of projects in 2016. Through this work, the Blind Mass Orchestra was born and subject to artistic and abstract experimentation in the form of Orecchia’s video installations. The videos became the foundation of Orecchia’s woodcuts as they produced the first printable version of the series as a single digital “still” image. He had made drawings while partnering with the artists at The Centre for the Less Good Idea, which opened up an opportunity for collaboration on a series of prints with Master Printer Jillian Ross and the team (including myself) at the David Krut Workshop (DKW) in 2018.

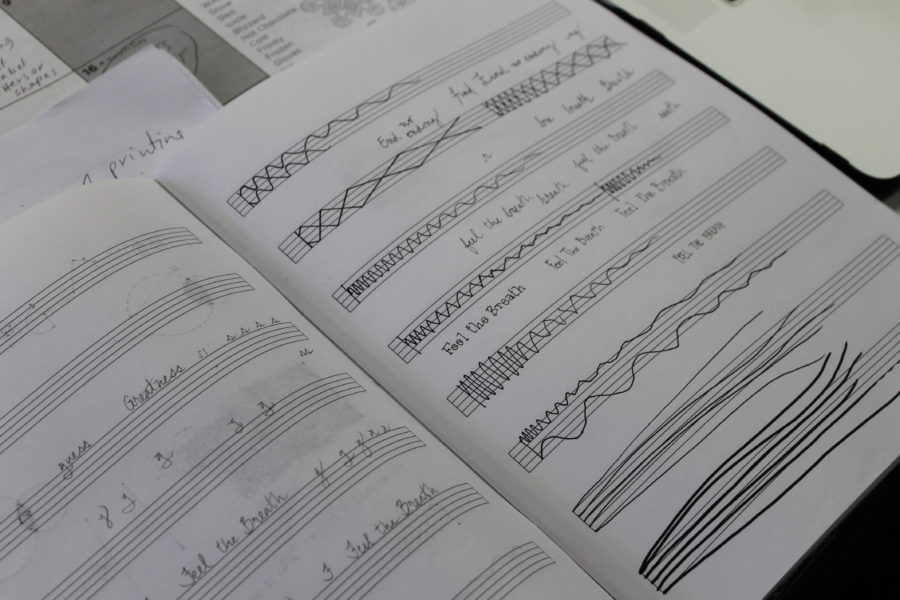

Lower image: Experimental musical score notes/drawings by Orecchia

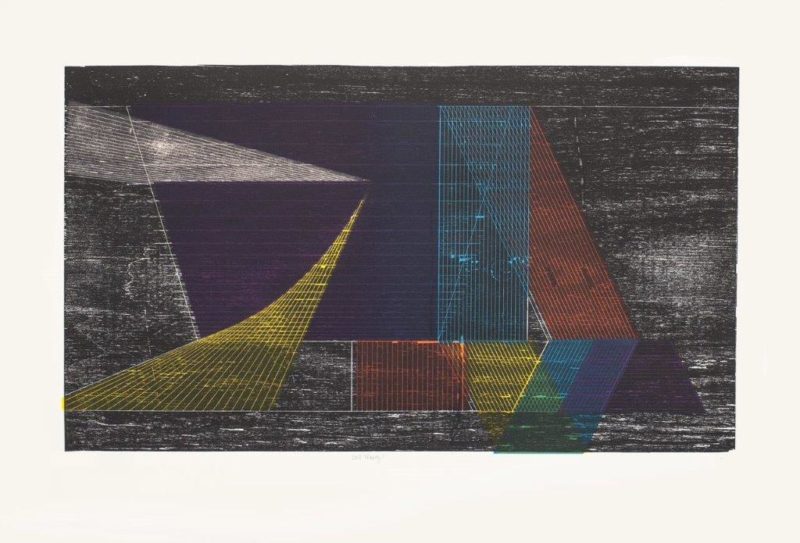

In my experience as a printer, I find that artists often choose to work with more than just one technique. Of course Orecchia being a self-taught musician on the brink of a solo exhibition was no exception, resulting in 12 etchings and 4 woodcuts. In his woodcut series of four, the first two, Still Moving 1 & Still Moving 2 consist of both monotype and intaglio. Technically this meant each layer needed to exist in harmony with one another, just like the different sounds in a piece of music.

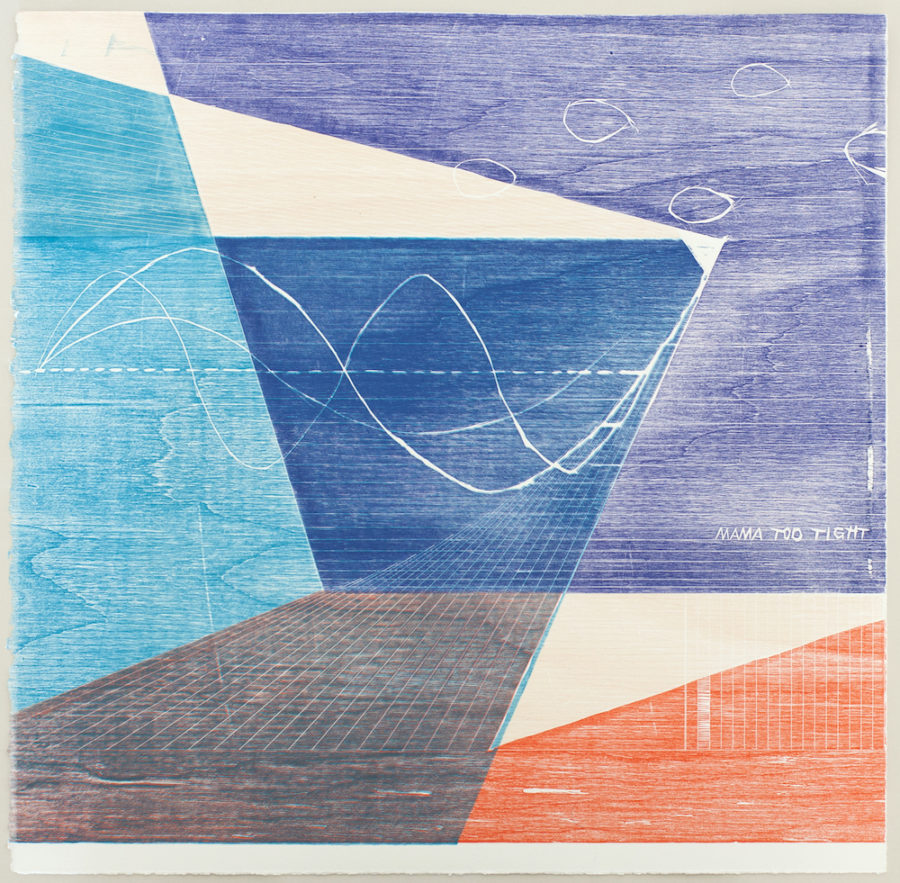

The series began taking shape once a wooden matrix was chosen and laser-cut using a section of the aforementioned still image. An acetate tracing of the laser-cut matrix was made in order to isolate sections of the image to be printed in specific colours, which became the first layer. In an effort to highlight the vibrancy of the colours and the wood grain, separate techniques were implemented, thus creating the differences between Still Moving 1 and Still Moving 2.

Although both versions require certain sections of line to be inked and wiped intaglio style, the first print takes it a step further by inking up the entire matrix to reveal the extent of the wood grain. Evidently, the monotype layer is the most noticeable commonality between the two prints, each of which exists in an edition of three.

(Edition of 3)

Right image: Mixed ink and ink scrapers/spatulas

Evidently the connection between video and print in Orecchia’s works can be seen in the linear and compounded nature of the colours. It’s quite paradoxical to think that a monotype can be part of an edition, and yet these woodcuts manage just that. The translucency of each colour places emphasis on the level of control and subtlety required when inking the woodblocks, almost as if the ink needed to give way to the grain just enough for the wood to breathe life into the print.

Right image: Disruption 2, 2019, Lazercut, woodcut on Somerset Satin White 300gsm, 42.8 x 44.3 cm

(both editions of 3)

The last two woodcuts in the series of four came with some interesting challenges for Orecchia as he was given a set of instructions to carve/implement into his matrix. The instructions came from artists he had directed in previous performances, and read as follows:

Trace your most memorable liner note experience - Chad Cordeiro

Draw a fully dressed sine wave going to church. - Simnikiwe Buhlungu

Make space between limbs and the point of interaction - Mele Broomes

Draw with the force of a camel - William Kentridge

Orecchia’s first response to the challenge was to divide the matrix into two parts. He then carved shapes, lines and text he believed related to the instructions into the block. In Disruption 1, he added three distinct lines in the form of waves, as well as text which reads, “MAMA TOO TIGHT”. In Disruption 2, he added a line and a number of spheres, two of which were much larger than the others. An interesting exercise is to see if you can identify all the elements within the works.

Never could I have imagined the impact these works would instill on my perception of sound as a printed object. Usually when I think of sounds or musical notations, I envision them as small objects transfixed in and between lines meant to be read from left to right, much like the Roman alphabet. Not once did I consider the possibility of sound being symbolised as translucent colour-filled shapes suspended in liminal space. Who’s to say all of us aren’t just shapes suspended in liminal space during this time in lockdown? It seems to me like we’re already transfixed in and between the everyday lines of our designated topography. Now more than ever I see colour in everything, I suspect it might be synesthesia. Perhaps that was Orecchia’s intention all along…

During these trying times, I urge you to consider art as an escape. Art will survive – it always does, if not through our collective actions to preserve it, then in what remains of our minds.