02.09.16

Blogger: Jessie Cohen

To celebrate Women’s Month, the DK Bookstore hosted an exhibition of all-women artists, which is on display for just a few more days. To mark this moment, I interviewed four female artists who we represent to gage how they perceive their gender to impact their practice. The responses vary – from reflections on the female subject position during the apartheid years to addressing the limited progress of women in the arts in SA today.

Being a woman in a world which celebrates women less than men, makes being a female artist quite a lonely journey. I first became aware of the lack of female representation in the art industry in 2014 when I was one of eleven shortlisted artists invited by Living Artist Emporium, a gallery in Johannesburg. Only as I was leaving the gallery did I realize that I was the only woman who was shortlisted. This baffles me because at university there was the same number, if not more, of girls than boys.

What happened to all those girls?

How is it that there are fewer women than men exhibiting in galleries?

It definitely isn’t because women are lesser artists.

While it isn’t a bad thing to push oneself, it often feels like one has to work extra hard as a woman just to be considered.

The South African art scene is changing – we’re seeing more women challenge the status quo and more great women artists on the front-line, such as Zanele Muholi, Lady Skollie, Mary Sibande and Tony Gum. This means more women heroes for girls to look up to.

We cannot underestimate the importance of heroines in society especially when you think about how little female leaders, or even just female main characters, are in stories young kids are exposed to: extremely few.

How are girls supposed to feel about themselves if they are never shown that their stories are important?

This gap in representation limits girls and young women so it is imperative that we work on dismantling these structures. It is important for me to produce and represent a female narrative.

In the formative years of my art-making practice and my teaching, it was race rather than gender that mattered in the South African context. My race privileged me with access to education, work and representation in exhibition spaces. Women were prominent in my tertiary studies and in the gallery domain – I never experienced a dominance of men in the art arena. Being a woman has not been an impediment, nor has it defined me as an artist or teacher.

In the late 70s/80s, I engaged with feminist debates that meant addressing historical gender roles and to re-evaluate the arts in relation to what was seen to be “fine art” and what was deemed “craft” – given inferior status as it was seen as “women’s work”, as discussed by Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock. I continue to address the fine art/craft categorization in my work and resist definitions of myself as a “feminine” artist with “feminine sensibility.”

Unfortunately, there is little gender equity anywhere right now – and the art world is no exception, but I have always believed that if one is willing to keep one’s head down and work; applying one’ s full intellect to the job; you will endure.

As a woman artist who chose to start having children at the age of 25 and marry an artist I have experienced hurdles and sacrifices to making art. What every artist needs, irrespective of their sex, is a space to work and the money to afford them the time to work. What I have struggled for is the balance of earning a living, home, children, pleasure, friends and making art. My parents, and especially my father, who was a strong man, always encouraged me to see my path as an artist, to take risks and not be distracted by conformity. This encouragement helped me persevere as a mother, a teacher, an artist and a wife. It’s like running a marathon while you’re hanging out the washing, planning the dinner, sketching a new image on a canvas, supervising math homework and finding joy in it all. But, it takes being prepared to run a marathon and not just sprint to success. I have been fortunate in the opportunities that have been available to me as an artist, especially as a white South African artist who’s work is more universally relevant than engaged in local political debates.

As a fine artist and as a filmmaker, I’ve not encountered bias on account of my gender. What did prove difficult was my decision to go abstract perhaps because South Africans want art that they can clearly decipher. At one time, around the eighties, there seemed to be more women than men artists in SA. In my generation, women were expected to do the household chores. Today, domestic labour is more shared so women can concentrate on a profession.

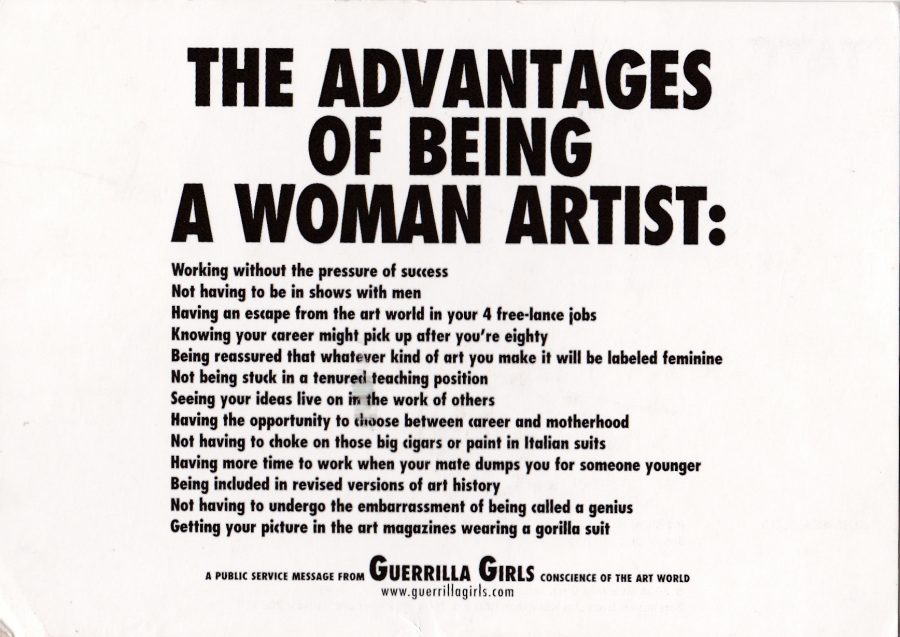

The Guerrilla Girls – the all-female US collective – speak about certain “advantages” of being a woman artist, which I find interesting.