18.11.15

Blogger & photographer: Jessie Cohen

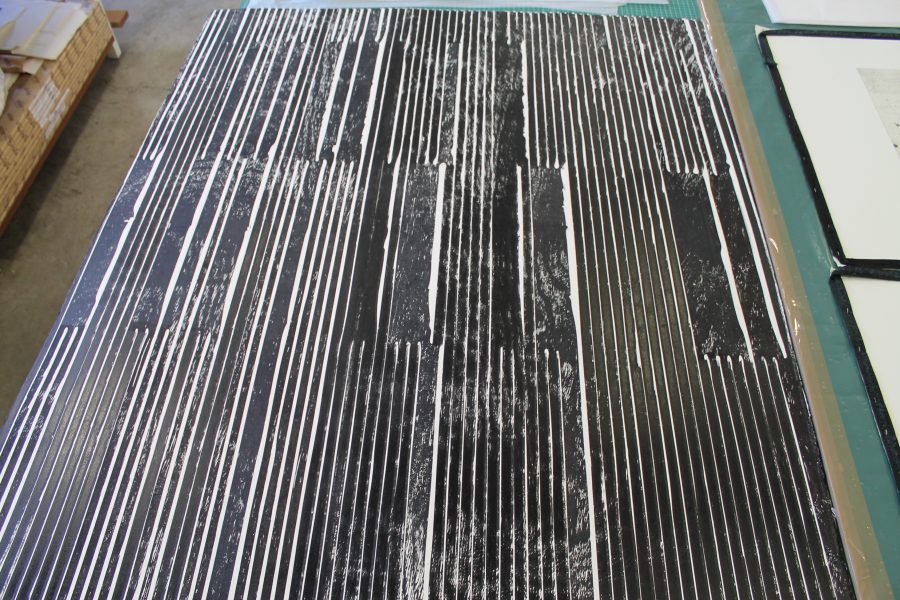

At this time of year, printers at AOM are wrapping up projects from 2015. The atmosphere is light but focused. This week, Sbongiseni Khulu is printing the final editions of Mary Wafer’s Veneer with the help of Neo Mahlasela and Martin Motha. They work from a laser-engraved woodcut made from plywood, which requires hand printing as it is too large to go through the press. Sooth to say, the process is labour intensive.

The process explained:

“We begin as per usual”, Sbongiseni says as he points to his tools. “We have our ink and our rollers – small, medium and large – with which we coat the woodcut evenly, put the paper on top and cover that with acetate to protect the paper. Then we use pressure-inducing instruments (which look like elaborate door knobs) to push the ink into the paper. We lift the paper throughout this process to check for an even application of ink”.

Sbongiseni waxes lyrical, telling me that “the beauty of working with wood, as opposed to lino, is the marks you get with the character of the wood grain.” He is under no illusions about the painstaking process, adding that “with woodcuts, the matrix is less predictable to work with and, of all the printing methods, it puts the most strain on your body.”

For printing Veneer, 400g paper is used. This is thicker than usual, but it is necessary for such a large piece (127 x 152cm) for which thinner paper would curl at the ends. Another benefit is the high durability.

It is important to note that the paper is not wet in this instance. For woodcut prints, this tends to be the case, because, as Sbongiseni tells me, “the paper must be dry to achieve a clean-looking print. If it were wet, it would pick up the marks more easily but it would present problems later when it dries as it would shrink. As this is a two-layer print on a large scale, we cannot be sure it would expand and shrink again to the same size”.

How hard can woodcut printing be?

“Put it this way”, Sbongiseni grins, “if I did this everyday, I could cancel my gym membership.”

He mulls over his statement. “Actually, printing from a woodcut this size is more mentally demanding. You have to be in a patient mindset and have the stamina to continuously fix parts along the way”.

Veneer is a two-layer print. Both layers are black but the second layer is applied off-kilter to create a doubling effect. Sbongiseni brings out a proof to give an idea of the final result:

Veneer is an edition of ten varied prints. Each print will contain different areas that are blocked out on the second layering of ink.

Afrobeats play in the background with steel drums setting a fast but steady pace. The music reflects the difference in rhythm between the Veneer printers and Kim-Lee Loggenberg, who is working solo, cropping editions of Mischa Fritsch’s Pointless and Proxy-me-tree, which she printed last week. While the former set work quickly, the latter takes a slower, steady approach.

For your average punter, this would be a daunting task: both of Fritsch’s works have gone through an exact printing process, with layers added over time, and now the task of cropping and tearing must be flawlessly done. Not a single tear or measurement can be out of place. But for an experienced printer like Kim-Lee, “it’s therapeutic. It requires focus but no stress.”

Tune in later this week for an update on our ongoing workouts at AOM.