Blogger: Jessie Cohen

2015-11

On returning to Johannesburg after an intensive three-week lecture and printmaking tour of the US, Stephen Hobbs is buzzing with enthusiasm and filled with inspiration. He spoke with our blogger, Jessie Cohen, to give a sense of what it was like to visit and make art in the so-called “armpit of America” (Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis) as well as Connecticut and New York.

With candid passion, Hobbs reflected that his trip was “a crazy idea of David [Krut’s] because it crunched so much travel and production into such a short space of time”. The tour was organised by Meghan Johnson from David Krut New York gallery, incorporating thorough fly-by visits to five cities in five different states, most of which Hobbs had never visited before.

For Hobbs, this was an opportunity to apply his expansive knowledge of urban change in South Africa to a different context. He said that while on the tour, “the basis of [his] thinking was in urban change – grappling with notions of ‘my city’, ‘my art’, urban decay, grafting new ideas onto collapsed cities and ‘new utopias’.”

The fast-paced nature of the trip required Hobbs to digest city dynamics very quickly, sometimes operating with less than two days to lecture, make prints and orientate himself. Some might have found it exhausting, but Hobbs seemed enlivened by the momentum.

The tour kicked off in Detroit, Michigan, where Hobbs gave a keynote speech at the Third Annual Detroit Design Festival in connection with the prestigious Penny Stamps Speaker Series, held at the University of Michigan Penny Stamps School of Art and Design.

Hobbs spoke about defensive architecture in relation to his art (videos, installations, photographs and sculptures), in which he uses wartime camouflage painting to depict how urban planning can turn our cities into battlegrounds, as has happened in Johannesburg in connection with “white flight”.

Click to watch Hobbs’s lecture, titled Defensive Architecture.

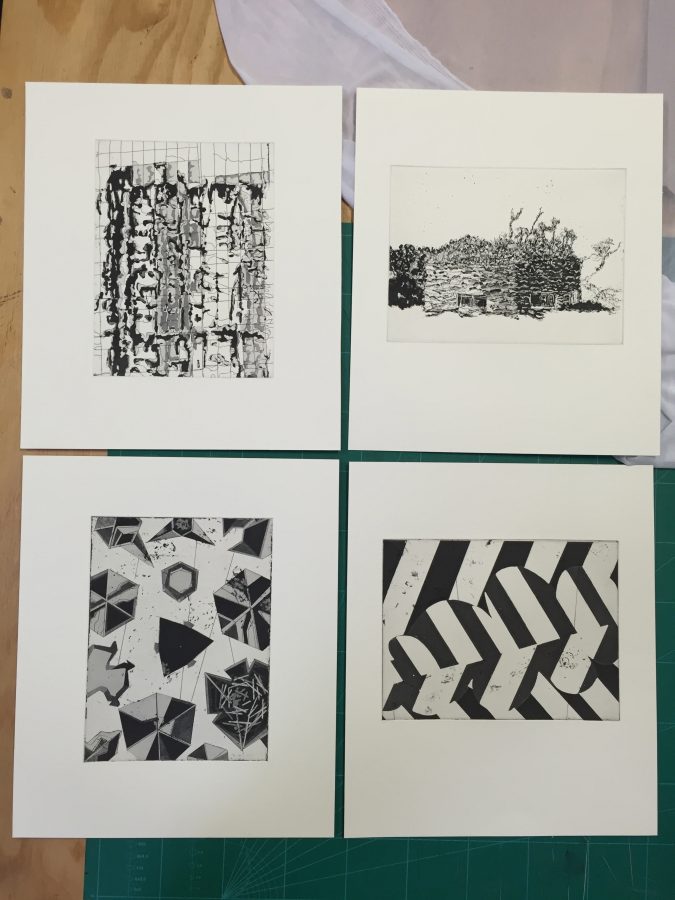

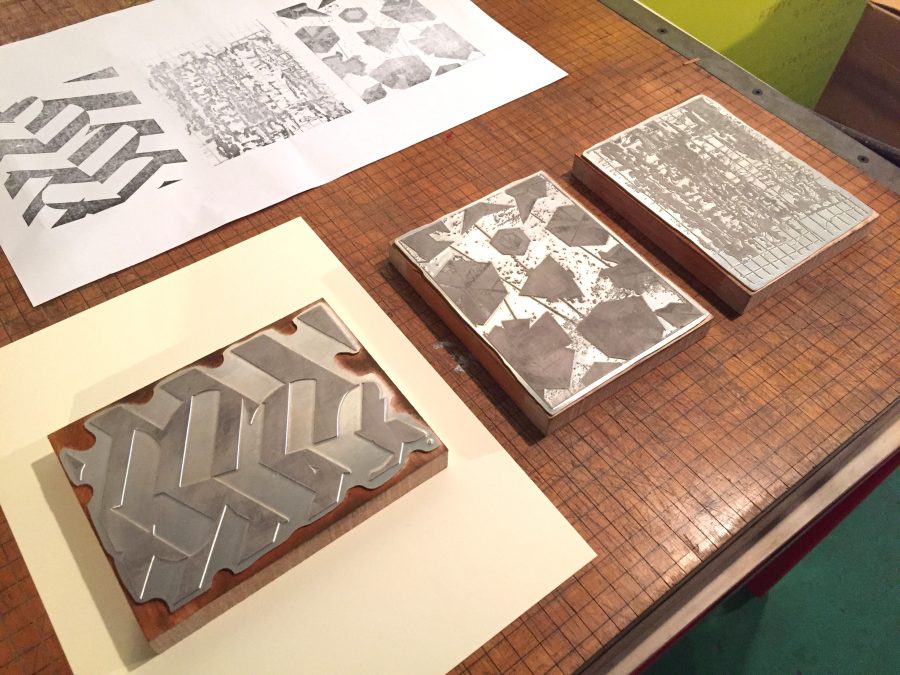

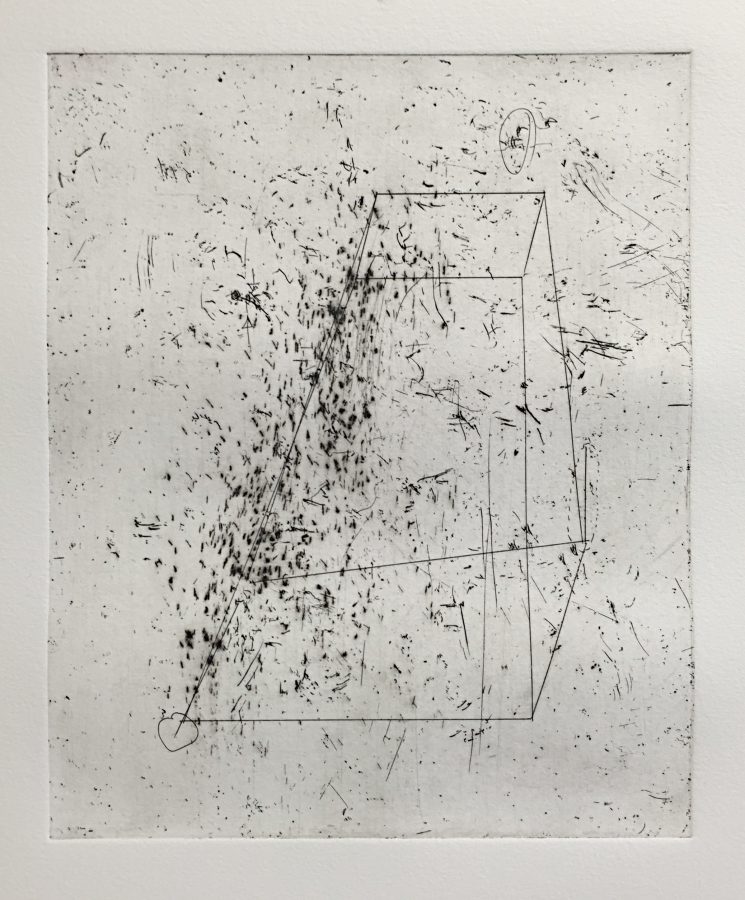

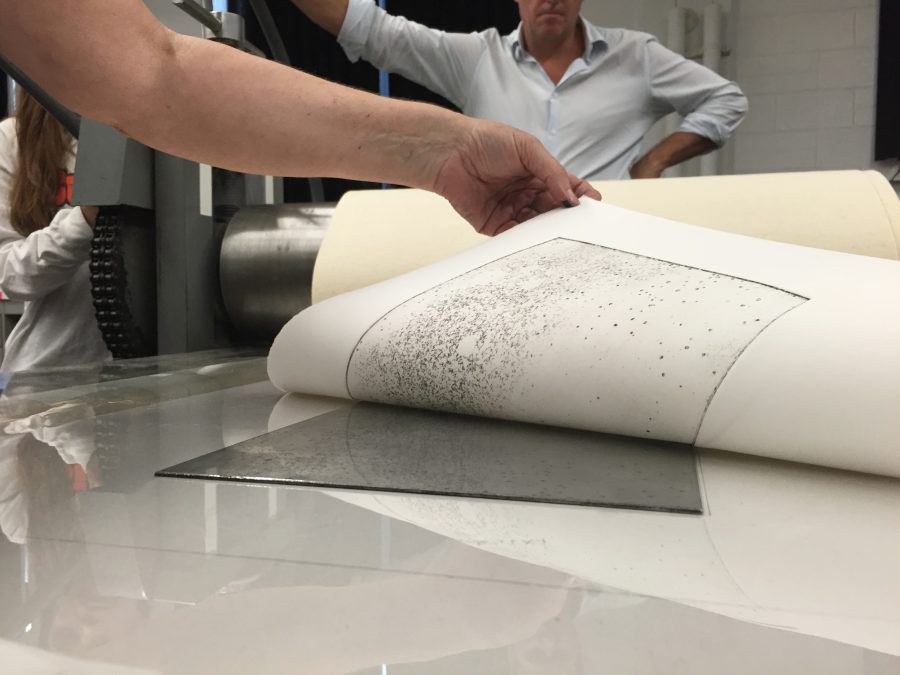

During his six-day stint in Detroit, Hobbs spent time at Salt & Cedar Letterpress, where he produced a series of letterpress prints, titled “Special Grids”. These experimental prints were executed organically as manifestations of Hobbs’s reactions to his new environment.

Hobbs: “Letterpress is a printmaking method which I hadn’t worked with before. When I arrived, I was overwhelmed by the range of typefaces. I gravitated towards already assembled words in the printers’ trays. I came across the words ‘Detroit’ and ‘heavy’. They chimed with me, so I ran with that”.

“Hobbs selected tangible and conceptual aspects of the city’s current state and merged these with imagery derived from dazzle camouflage, transmuted architectonic shapes, and geometric letterforms. Following the initial runs on a Vandercook SP15 cylinder press, Hobbs added to the substraits with heavy impasto paints, brushed or splattered pigments, and architectural drafting mediums. Taken as a whole, “Special Grids” defies conventions of printmaking, editioning, and notions of uniformity. It traverses an array of histories, dimensions, and sites of contest, while pointing to the precarious state of cities undergoing radical physical change” – Salt & Cedar Letterpress prospectus on “Special Grids”.

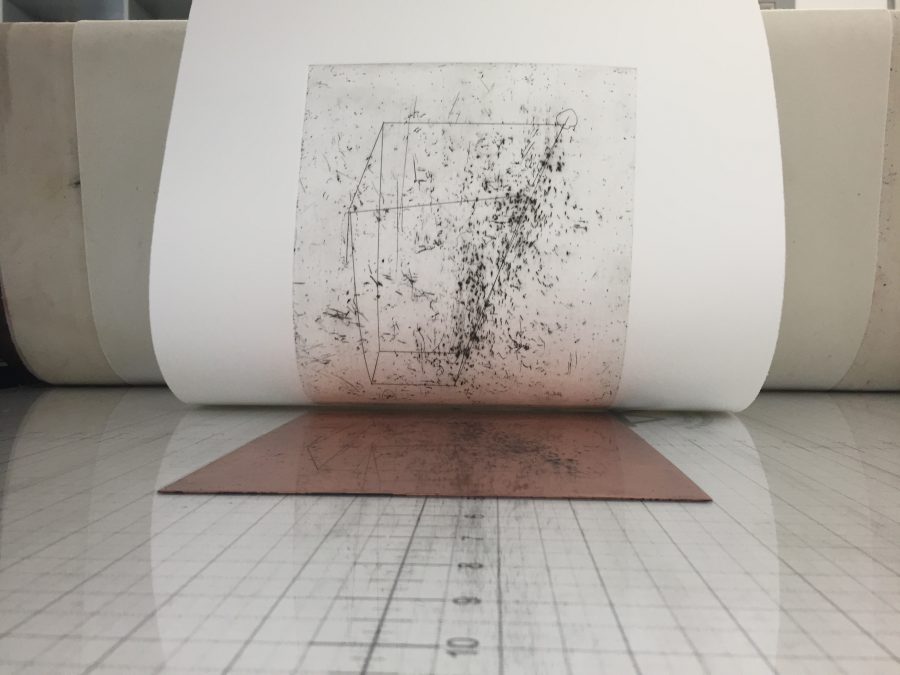

It is interesting to note that the “Special Grids” series is an extension of a previous set of prints which Hobbs recently made in South Africa with DKP master printer Jillian Ross at our workshop in Arts on Main. Hobbs selected a series of prints, titled “Buildings, bombs, bunkers and clouds”, to constitute the foundation images for his letterpress prints as a way of building up a dialogue on urban change between the two countries within his art.

The technical process for using “Buildings, bombs, bunkers and clouds” involved translating the prints onto magnesium plates through photographic transfer.

As one of South Africa’s most well-known public artists, Hobbs is constantly alive to processes of urban change. In his printmaking, he tries to incorporate a light, direct style characteristic of his urban art.

While at Salt & Cedar, Hobbs fondly recalls “playing with materials and mark-making while engaging a strict printing process”. This was fitting with his usual style of work which he describes as “a perpetual process of tearing up, scanning and reassembling.”

To orientate himself in a new city, Hobbs spent his first day driving across Detroit with Greg Baise, Public Programme Director at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit.

With Baise as a local guide, Hobbs explored the post-industrial areas of downtown Detroit, which gave him a sense of the urban sprawl. He also got a feel for distinct cultural areas, ranging from One Mile, the Irish suburbs, to various gentrified parts. Hobbs saw the drive as invaluable to his understanding of the city and how he produced work there.

Hobbs was reminded of Johannesburg in terms of the tangible impact of white flight, which is also relevant to downtown Detroit.

Hobbs: “Detroit was once a promising, thriving place. It used to be the world’s biggest producer of cars, much like Johannesburg was the fastest growing city in the world between 1930 and 1960. Today, observing growth in these spaces is something quite different. As I travelled from city to city, I’d orientate myself and then re-structure my talks so that what I said would be attuned to the global cultural trends connected to the urban development and decline happening in that place.”

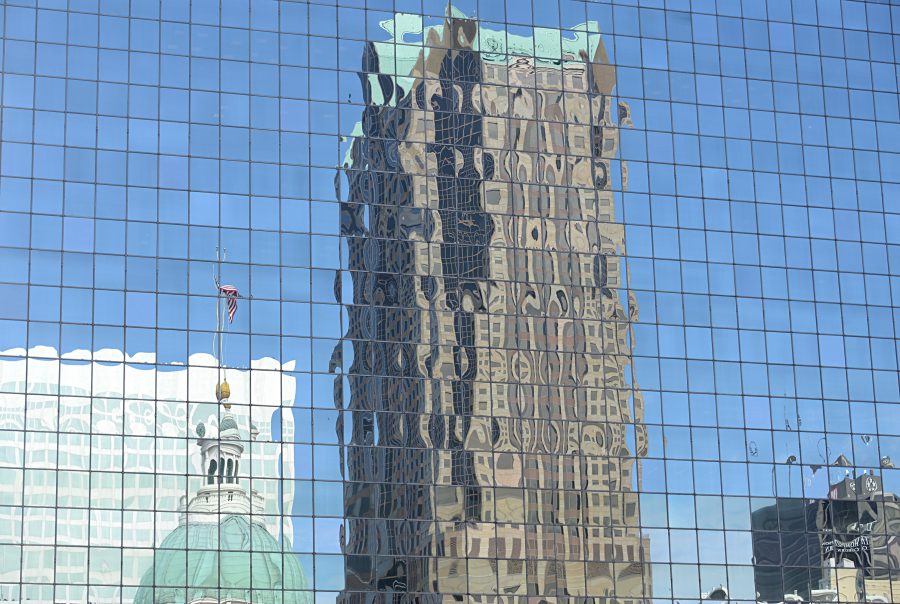

After a fascinating drive through Detroit, Hobbs chose to orientate himself in the same way when he arrived in Cleveland, St. Louis, and New York City – “cities built with the American Dream strongly in mind, and the remaining footprint of their rapid growth bears testament” – Hobbs.

Hobbs’s “Special Grids” prints and Penny Stamps lecture were met with curiosity and positivity. He partly puts this response down to “a fantastic loop between the media, the marketing of the Penny Stamps talk series and the popularity of the Eastern Market which coincided with my visit”.

At the Eastern Market, locals appreciated that Hobbs’s style of art is not just studio-based, but directly engages the environment in which he works.

Contrary to the common perception that Americans can be dismissive of outsiders expressing critical views of their social structures, Hobbs experienced an openness: “I wasn’t talking to middle Americans but to an informed, curious, open-minded bunch of people often in university contexts – people who have a deep interest in urban change and the issues around that.”

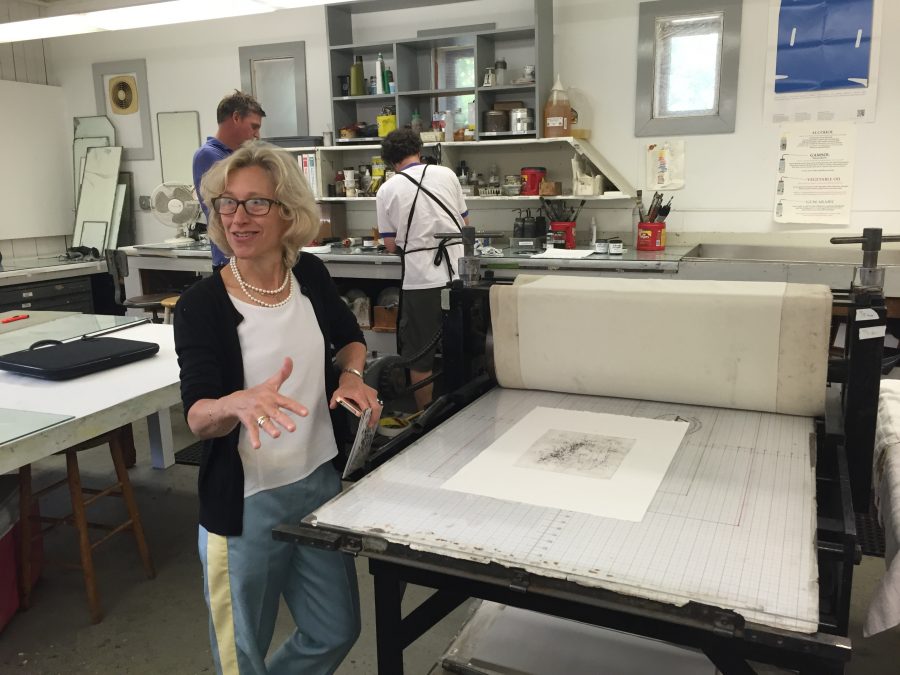

After Detroit, Hobbs headed east to the wealthy state of Connecticut, New England. Here, he delivered a lecture and conducted a print demonstration at the Centre for Contemporary Printmaking (CCP).

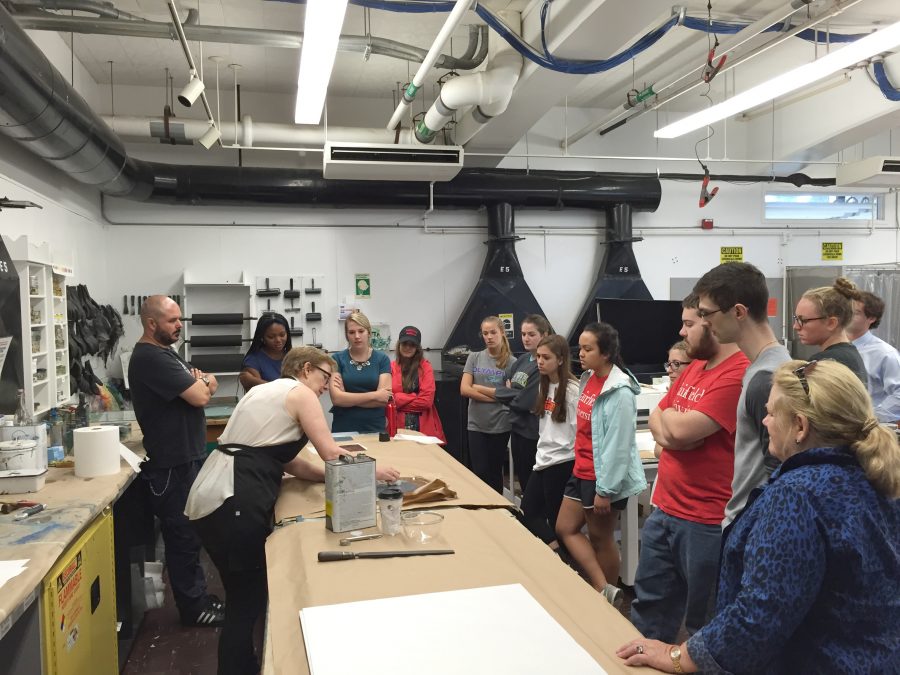

During his two-day visit, Hobbs also went to the Fine Art department at Fairfield University where he lectured on printmaking and did a print demonstration with the undergraduate students.

Of his many adventures in Connecticut, Hobbs was most excited to reminisce about his trip to the historic Philip Johnson Glass House. “It is a massive estate”, he explained, “made up of a series of concept-driven buildings – one for sculpture, one for reading, etc. The place was amazing to me because one of my passions is experimentation in architecture and landscape design.”

Hobbs: “The Glass House is a manifesto for Johnson’s ideas about landscape, architecture and contemporary art. It is an awe-inspiring homage to his thoughts on art and architecture. Frank Stella and Andy Warhol were famously hosted there.”

Next stop: Cleveland, Ohio. Hobbs stationed here for four days, during which time he went to the Cleveland Institute of Art to launch his media mesh screen that had just been installed on the side of the building and screened some of his work there. He also delivered a talk on urban change to the faculty.

While driving through Cleveland, Hobbs observed some striking similarities to Johannesburg’s social terrain. He saw that “the effects of post-industrial collapse were evident in places like Cleveland and Detroit where urban development abruptly stopped in the seventies, leaving entire communities in financial ruin.” Hobbs added that “while South African history is very different, we see something similar in terms of the effects of post-apartheid degeneration in areas.”

Hobbs continued: “Much like in South Africa, in parts of America we find a starkly drawn juxtaposition between wealth and poverty with privileged areas flourishing while other spaces of the city are left to stagnate.”

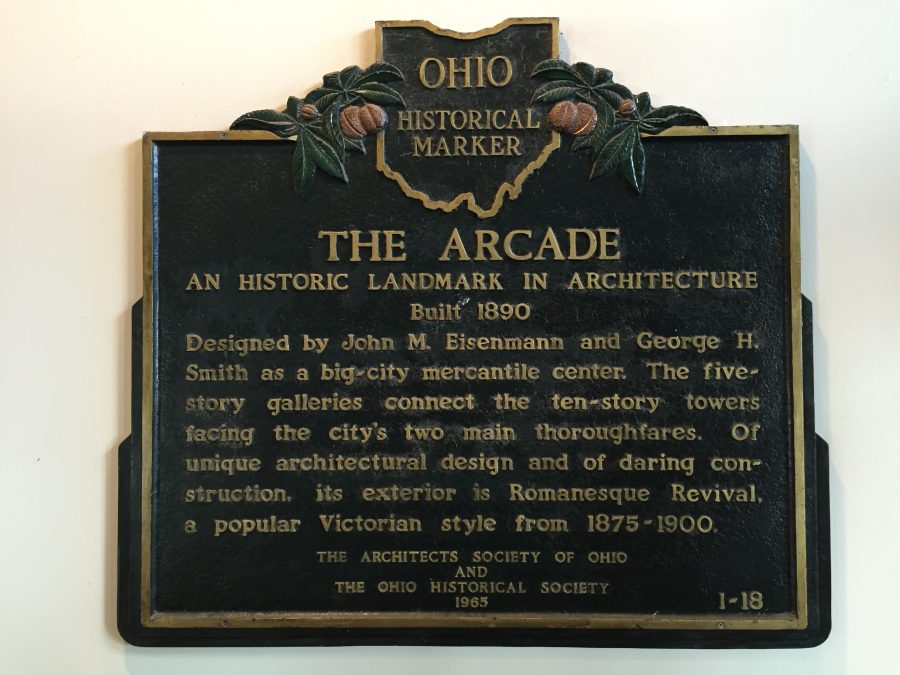

On the drive, Hobbs was shown the original arcade in downtown Cleveland.

On arriving in St. Louis, Missouri, Hobbs had just one and a half days to orientate himself, deliver a lecture at Washington University and do a print demonstration with the students there.

Orientating himself first, Hobbs paid close attention to signs of regeneration and decay.

Together with Washington University’s Professor of Art, Lisa Bulawsky, Hobbs conducted a workshop at the university. He instructed the students to create a narrative of their own city using collage and a personal take on camouflage.

On his last day in St. Louis, Hobbs met local journalist Eileen G’Sell for a three-hour walking tour of the city.

For Hobbs, the most memorable part was seeing what remains of a large-scale apartment complex called Pruitt-Igoe. He described it as a “fascinating, failed housing condition”, designed – rather ironically – by Minoru Yamasaki, the same architect of the Twin Towers. Hobbs felt that it resembled “a dystopic image where post-apocalyptic nature consumes modernism.”

For an in-depth commentary, click here to read “Post-Apocalyptic Aesthetics? A Pruitt-Igoe Walking Tour” by Eileen G’Sell: https://commonreader.wustl.edu/post-apocalypse-aesthetics-a-pruitt-igoe-walking-tour/

Hobbs’s roller-coaster ride through five states ended in New York City, New York. He gave a talk at New York City College, where he noted “the university had fortress-like architecture with beautiful gates opening into the city”. He appreciated its Harlem location, for which he attributed the university’s “cultural richness and diversity”.

Here, Hobbs engaged graduate students on their work and visited their studio spaces. He saw that many were dealing with similar themes to South African students for whom identity politics is a key concern.

Hobbs encouraged the students to consider the relationship between their use of materials and conceptual intent. This was followed by a talk, which, he said, “felt more like an intimate group tutorial and turned into an intensely focused group session.”

Navigating NYC:

Thinking back on his overall experience, Hobbs reflected that “America has a simple narrative of social change. In essence, they got greedy. Companies got rich, they over-expanded and over-built and then just disappeared. It’s a very different economic paradigm to South Africa, but the similarities between our social geographies are there and need to be unpacked”.

As we neared the end of our conversation, Hobbs leaned forward and looked me square in the eye. “Ultimately”, he asserted, “in and amongst all the travelling, lecturing and printmaking, the real work was building foundations between institutions on an important subject. I was there to provoke a much-needed conversation on the role that art plays in urban change”.