Mask Self-Portrait, 1999

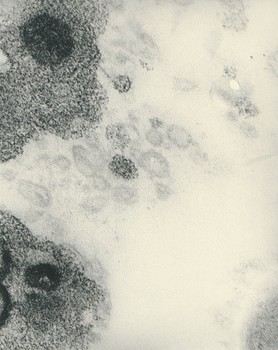

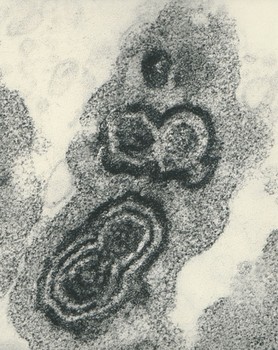

“At the end of 1996 I was invited to make a response to the Human Genome Project. I decided that I would make a diagnostic genetic self-portrait. I met with Dr. Dorothy Warburton, a geneticist at the Cytogenetics Laboratory at Columbia Presbyterian and through Dr. Warburton I made contact with other scientists who collaborated with me. The project had begun as a kind of harvesting of my own biology that might comprise a self-portrait. What I kept feeling was, at what point does my portrait move from generic to personal.

“I began to look at the forensic sciences and moved away from a diagnostic portrait. I had begun making handprints in 1993 and it slowly dawned on me how to build this very multi-layered portrait made up of scientific and pseudo- scientific images that were whimsical interpretations of my subject. I looked at images of myself that were as private as I could imagine, that either signify or reveal my genetically unique self.

“How much visual comment could I make onto the material to transform it to metaphor. Each of the prints in Genetic Self-Portrait are made to have a very specific surface, color, tone , contrast , density, and scale. This biological self-portrait is one where each element is a different way of presenting a private aspect of myself to the world.

“The irony in Genetic Self-Portrait is that it remains an anonymous portrait, it is neither ethnic, nor race, nor age specific, yet at the same time these are my most private parts.” – Gary Schneider.

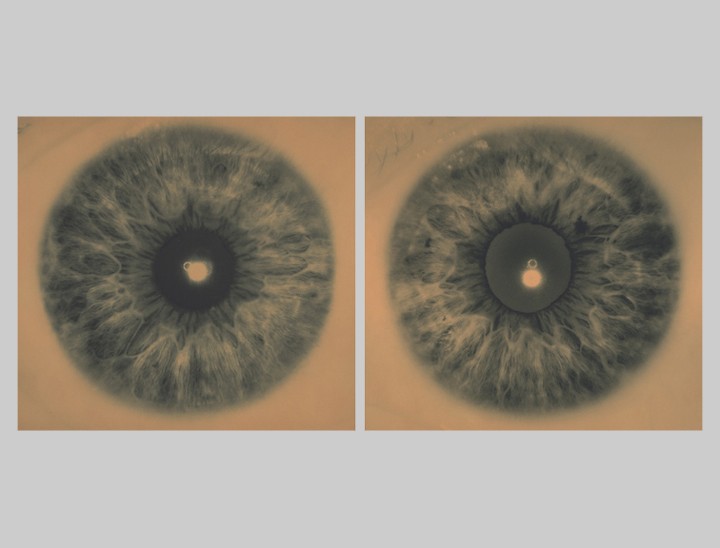

Irises, 1997, 73,66 x 162,56 cm

Schneider is fascinated with the concept of the human genome project as an instruction book for a human being. To construct his images for the Genetic Self-Portrait photographic series, he peered into the microscope at his own genetic blueprint, extracted details from cells, fluoresced chromosomes, genes, DNA sequences and used them as forensic proof of identity, but also as personal pointers to the self, and thus an emotional response to the new world of genetics – “these are my most private parts”. The conclusion is an intimate, novel slant on the traditional self- portrait. It is narcissistic, a trait normally, associated with the genre, but it is also a universal portrait.

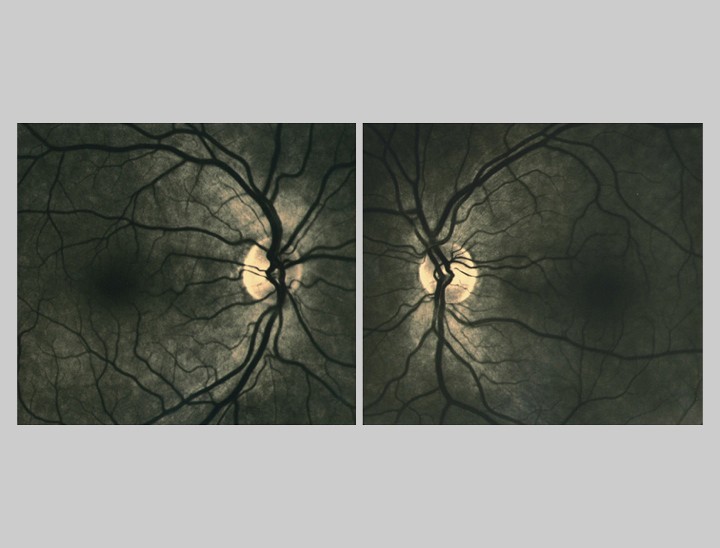

The Irises image was taken with a 35mm Fundus camera adapted to photograph the interior of the eye with a light source projected through the lens of the camera. Schneider chose this camera so that the light source would not interfere with the images of the irises. The focal highlight at the center of the pupil is in fact the reflected light source. It works effectively with the iris image by emphasizing the kinetic mandala effect and drawing the viewer in.

Foucault pictures the reciprocity of gazes apparent in Velazquez’ Las Meninas as, “the observer and the observed taking part in a ceaseless exchange”. This is equally applicable to Schneider’s Irises gravure. As viewers, we are arrested by the artist’s impassive, but profoundly mesmeric gaze. Schneider’s self-portrait as photographer / printmaker reveals to us the symbolic and physical heart of his art, the eye.

The work in the Genetic Self-Portrait exhibition ranges from images of his individual chromosomes made by a light microscope to panoramic dental x-rays. Schneider is known as a master photographic printer, and by combining his skill as a craftsman and selecting specimens for their aesthetic qualities, he moved beyond scientific descriptions to produce a personal portrait that asks us to consider how we are unique and where we stand on common ground.

Schneider had always been interested in alternative imaging techniques, and previous to this project he had been making images by imprinting his hands onto film emulsions. When he decided to include these prints along with the images he had been making with scientists, he realized that what he had been creating was a new kind of portrait. Ann Thomas, curator of photographs at the National Gallery of Canada, described it as a new approach that “challenges the traditional definition of the portrait, and revises our understanding of what it means to be revealed before the camera’s lens.”

By merging scientific accuracy with poetic resonance, Schneider has created a very personal illumination of how our individual identity is so closely linked to our broader understanding and use of the information contained in the human building blocks of our DNA. Through the personal exploration that went into creating genetic self-portrait, Schneider reveals that while we may always want to think of ourselves as more than the sum of our parts, our real promise might be found in looking at the 99 percent of ourselves we have in common with everyone else.

A publication of the same title is available for purchase from David Krut Bookstores at Parkwood and Arts on Main, Johannesburg, as well as at the Montebello Design Centre, Newlands, Cape Town. The publication is priced at R350.