David Krut Projects, New York is thrilled to be showing artist Vusi Beauchamp in The Cult of One, Part II until October 22nd. The exhibition follows Beauchamp’s The Cult of One, which opened at David Krut Projects, Johannesburg in July 2022. This is Beauchamp’s first solo exhibition with our New York gallery, and the first showing of his work in the United States.

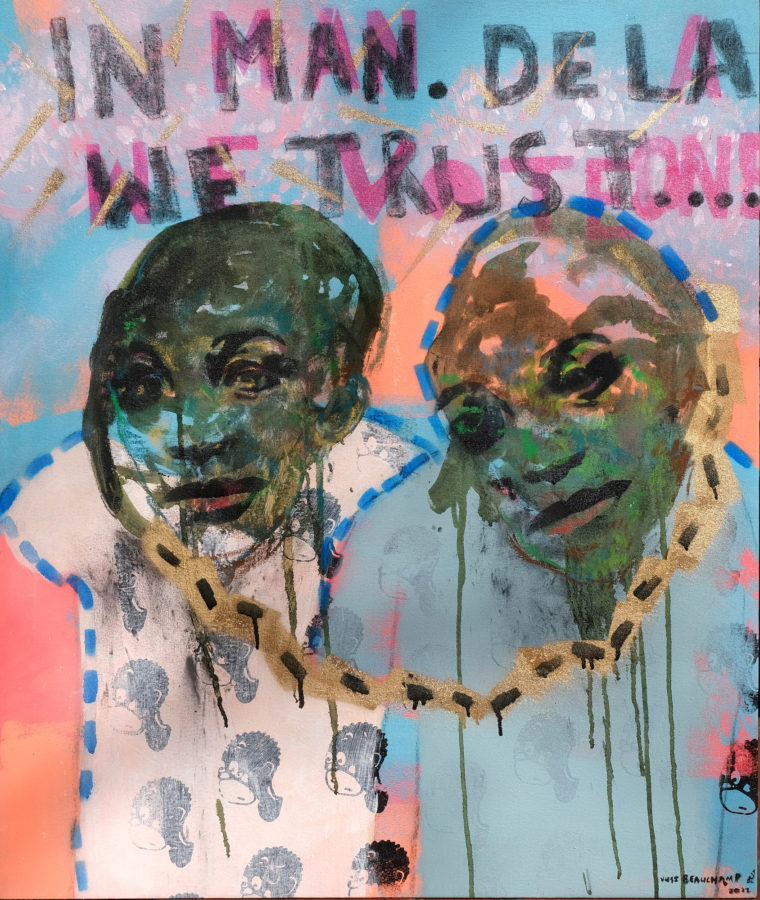

His somewhat controversial works comment on social issues, politics and current events in the “post-Rainbow Nation era” of South Africa, though they easily relate to the dissatisfaction felt by many international communities with regards to their political and economic leaders. The Cult of One, Part II features a brand-new collection of mixed-media paintings on both canvas and paper, along with a selection of the monotypes Beauchamp created at the David Krut Workshop from 2021-2022.

The following interview was conducted with Vusi Beauchamp in his studio by David Krut and Melissa Waters of David Krut Projects in Johannesburg on behalf of our New York gallery. Read on to learn more about Beauchamp’s artistic practice, the complex politics that influenced The Cult of One exhibitions, and much more –

Tell us a little bit about your background. What was your family like? What made you decide to be an artist?

I was born in Mamelodi, Pretoria.1 At my primary school in Mamelodi, my mother was a teacher. I always had an interest in art, you know, even from preschool, I used to draw. I would get upset when the lady that was the helper in our house would throw things that I made away. I felt like art was something that was a part of me. When I took it as a subject in high school, it became more of what I wanted to do with my life. There’s no one with an artistic background in my family. My father is a practicing attorney. With my mother a teacher, my family is a bit of an academic family, but not artistic.

The works in the The Cult of One exhibitions are set against a backdrop of the “post-Rainbow Nation” era of South Africa. How would you describe this particular time in the country’s history, for anyone who may not be familiar?

The term “rainbow nation” came about after 1994 as a way to promote unity.2 Post the Nelson Mandela era, Mandela sort of becomes a kind of propaganda machine, a propaganda tool, where it’s not about his values or what he stood for, or his intention for a post-Apartheid South Africa. Instead, it became where we are now, where it’s all about what we can take for ourselves. But at the same time, continuing to try to sell this Mandela dream or something like that. I mean, it’s complicated. The backdrop is very conflicted by itself. I just believe that the government today took on an already well-oiled machine that’s been in operation for maybe a few hundred years – segregating and delegating certain access to a certain class. For instance, the idea of a black middle class or the so-called “black elite” makes me think that there is a degree of economic classism happening.

I even see this in the history of African leaders, where when coming from a certain tribe, they exert a certain influence and create a privilege divide. It’s the backdrop of The Cult of One, where one thing becomes centralized to one power source in a way. For instance, there is what I would call a “Xhosa era” with Mandela and Thabo Mbeki.3 It just became more of a tribalistic entity and this colored the beginning of internal fighting within the ANC (African National Congress) after they came to power. But I also believe tribalisation has been a tool that’s been used since colonial times to divide and conquer – give special rights to one tribe or whatever, and turn on the other one. And it goes on that way, causing segregation as well. Like in Mamelodi township, there’s one section for Venda-speaking people, one section for Sotho-speaking people, and within that there will always be this interesting, weird village where people don’t get along.

But the idea of creating and nurturing difference, highlighting the difference between the groups of people, that’s where someone can come in as a so-called saviour. The separations become internalized to a point where they believe this is the way, the order of things where “we don’t like them, because in our history, these people did this” etc.

What are some of the main issues you explore in your work, particularly in The Cult of One exhibitions?

Issues of power and control and propaganda. The latter I see as always around us. Much more prominent when it comes to election time, where you see these political parties using the tools of Apartheid, tools of divide, to cause a bit of instability before the time of elections. They create these problems and they sell us solutions to the problem.

In the lead-up to elections or important events, they play videos of Apartheid brutalities, you know, like about the Sharpeville massacre, for instance.4 It’s like 10 o’clock at night, you’re watching TV and suddenly there’s a little documentary that’s played almost every year. It’s orchestrated, like a set menu of what you’re going to play to make the people angry, like, “That’s the enemy. Remember the enemy?” Meanwhile, they are still perpetrating similar crimes. I mean, you look at the Marikana Massacre,5 you know, does one eclipse the other? An African policeman running around chasing black folks. Ramaphosa had shares in the Marikana mine, he played a really big part in that massacre.6 But they try to find ways to cover this up with a bit of confusion. But it’s not concluded – nobody was prosecuted, there were no punishments, no guilty party, no consequences. So this is a mass killing by government, in the new South Africa, post-Apartheid. These conversations of power control are always there, but like I said, they all fly the new flag and put the new flag over the other one, but at same time, the struggles and attitudes are still there.

It’s just like capitalism – the brutality of it, the need to keep the system going. The need for there to be someone lower. For someone to thrive, you know, there has to be someone else suffering.

Regardless of the propaganda that’s always shoved into our faces before elections, the enemy is always Apartheid. But at the same time, the black liberator, the black president, is doing something just as sinister. The painting [Saviour] with the suicide bomber jacket is looking into the face of liberation, the face of change, and the imbalance between the have and the have-nots, describing dreams to people who are hopeful of a new saviour.

How do you think the issues you explore relate to political stories in America, and particularly to Donald Trump?

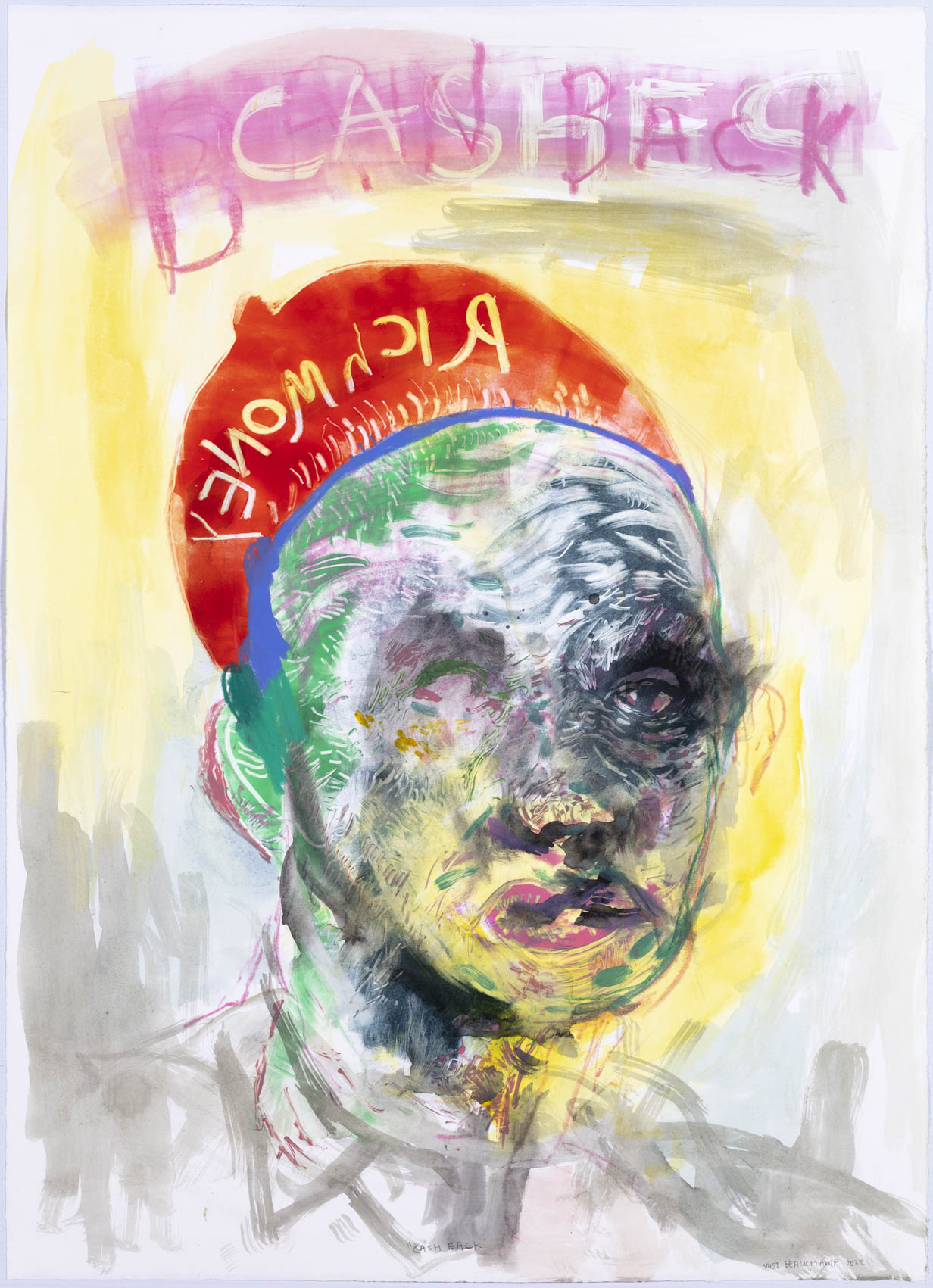

In the new party in South Africa – the EFF (Economic Freedom Fighters) – patriotism is taken to the extreme.7 And there are similarities in the tools of propaganda like a red hat with slogans that are almost ambiguous. In the case of Trump, there were times where he was sort of like commemorating followers of him that were actually very destructive.

The incident in Charlottesville is a good example, where Trump said something like “there were good people on both sides,” or “each had valid points” or whatever.8 But what valid points, you know? Anyone in their right mind knows one side is bad. But that’s how he builds this idea of a cult. He’s got a cult following, even now that he’s not the president. He seduced them with this right-wing rhetoric. And it’s similar in South Africa in a way with the EFF.

I use this in one of my works, Cash Back, with the red beret. It’s always interesting with the colors as well, like “rules of propaganda number one: the color red.”

What I find so interesting about the EFF and Donald Trump is that Donald Trump is far-right and the EFF would be considered far-left, but in a sense there’s so many similarities, and it just makes you think this whole politics thing is not really left to right.

It’s very interesting, yes. Julius Malema was on trial recently for the song “Kill the Boer.” His party was singing that song, which was inciting violence, murder and is offensive. And he was defending himself, saying that they were not saying “kill” but “kiss.” In court they played a recording and you can clearly hear that it is “kill.” Besides, everyone knows that song- it’s been around for many years, you know? So I mean, with Donald Trump, some of the things that he says, we call it fake news, truth and lies to confuse the whole thing, but the message is loud and clear. And his cult followers, they’ve heard the calling, they’ve heard what they needed to hear.

Who are the artists, authors, filmmakers, etc., who have really resonated with you and influenced your work?

In the film world, I’ll say Spike Lee. He did very interesting films about history in America, when there was still unrest. And of course it relates to conversations that are still happening now, of killings by police of unarmed black men.

I think it was in the nineties or something, when someone took a video of police beating up this black man. And it became almost like visual evidence of what has been happening to these black neighborhoods in America for a long time. His movies really resonate with me because he was talking about where he comes from, his neighborhood. The movies were very insightful in understanding where so-called subcultures of rap music come from and all that.

When it comes to other influences, I would say, K. Sello Duiker’s book The Quiet Violence of Dreams, which is about the inner workings of contemporary South African urban culture.

In the visual art world, I find interesting the artists that have a certain way of looking at things, who attempt to depict and reference a complicated way of dealing with pain, I suppose; Basquiat’s work, for instance. Because it falls under the conversations of body experience, something closer to what Spike Lee’s movies are about, showing the other side of the flag or whatever. And Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, as a means of commentary and creating a new way to look at things.

What’s your process like? Are you a planner or do you just like to start and see what happens?

I’m a planner. It takes me two days, after priming canvas and pinning them to the wall. I give myself two days to envision the works in my mind. And for each canvas, I’ll write a bit of a note, if something pops up. From there, it becomes easier to conceptualize, to concentrate on how I’m going carry that thought imagery-wise and how it will link to other paintings.

Important to my process is playing with text as well. I like to play in my mind with phrases and the color scheme. And I want the works to play against each other to certain degree. It’s almost like a planned chaos in a way. It shouldn’t look planned, rather like a mash up poster of now. Cause I think it’s a mash up of everything, you know, there’s just too many things happening at the same time, too many slogans that are new, some are old, some of them are taken out of context, but it’s like an interesting collage of post-Apartheid South Africa, or post-free South Africa.

I try to pick up on everything happening around me. It’s like an interrogation as well of what I’ve heard on TV or read in a newspaper or, some kid in a video or the history channel. The context is always interesting and different. But somehow there’s a connection to that where it just shows that it’s a human thing that we do.

Other references that I draw on are things like Greek mythology, African mythology, and finding a thread to tie them in, you know, to almost capture the zeitgeist of today’s leaders. One has to make reference to context, and text can assist in providing that information, like from newspaper headlines, but at same time, not trying to be a comic strip, but something that can be relatable.

Had you done any printmaking before your collaboration with David Krut Workshop?

At university one of my subjects was printmaking, but I never liked it. The technicality of it didn’t give me much freedom, of freely enjoying brush strokes. It was something that I felt stifled my gestural painting and my methods of putting things together in a work.

So at the workshop in Johannesburg, it took a while to break away from that mentality, from the way I usually worked. The workshop made it possible for me to bring together my gestures from painting on canvas onto paper to making monotypes.

So you’d never done monotype before?

No. Even when I was studying printmaking, it was mostly just carving. I may have done etching, I tried. I don’t remember, it’s quite long ago now.

And you’re interested in doing etchings? You said you might be…

I am a little bit. I don’t know what to expect, but it would be an interesting adventure.

Endnotes:

1 Mamelodi is a township that was set up by the then Apartheid government northeast of Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa.

2 South Africa’s new constitution took effect in 1994, marking the official end of Apartheid.

3 Xhosa refers to a South African people traditionally living in the Eastern Cape Province; Thabo Mbeki was the first deputy president of the new South Africa and the second president after Nelson Mandela.

4 The Sharpeville massacre occurred on March 21, 1960, when police officers opened fire on a group of people peacefully protesting oppressive laws in a black township in South Africa, killing 69 and injuring more than 180.

5 The Marikana massacre occurred on August 16, 2012, when the South African Police Service (SAPS) opened fire on a crowd of striking mineworkers, killing 34 and injuring 78.

6 Cyril Ramaphosa is the fifth democratically-elected president of South Africa, from 2018 – present [2022].

7 The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) are a far-left, South African political party formed by former African National Congress (ANC) member Julius Malema and others in 2013.

8 The Charlottesville attack occurred on August 12, 2017 when a man deliberately drove his car into a crowd of people peacefully protesting the white supremacist “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, killing 1 and injuring 35.