Throughout the month of April 2011 Jessica Webster’s second solo exhibition titled Original Skin was on display at the David Krut Projects Gallery. The exhibition includes a selection of works on paper and paintings which explore modernist notions of surface and skin.

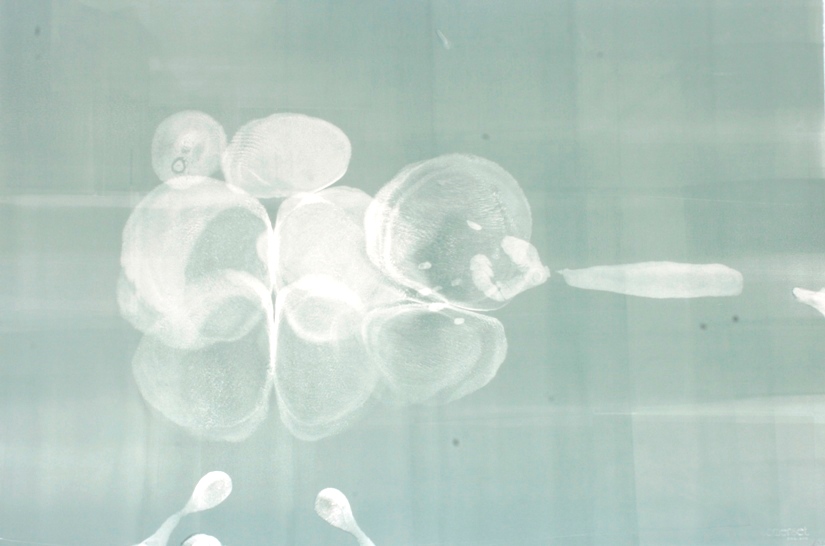

Webster works primarily with oil paint and wax. Her work is based on a material and theoretical investigation and understanding of surface. The artist addresses these issues in her monotypes, by placing her physical body onto the printing press, using her skin to displace the ink and creating autographic marks. Webster creates non-narrative works and focuses on the simultaneity between the subject and the surface, the real and the not real. Her conceptualisation of surface therefore occurs between form and content, as simultaneously inside and outside to these issues.

Preceding the Exhibition opening, Webster was interviewed by Juliet White in January of 2011:

How would you frame this body of prints in relation to your concerns as a contemporary painter?

Critical painting can evoke a special kind of visuality and affect that slips and escapes the attempt to find a linguistic equivalent, and this to a large degree informs my theoretical and philosophical interest in the painted surface. There is a complex and controversial history to painting, where artists have taken extreme positions in both abstraction and figuration to either find this material and visual language, or try to negate it – in both cases an often frustratingly elusive task. The contemporary painter can now reach even further with reference to these art-historical movements, creating multivalent and intricately imaginative combinations that explore the science or philosophy, the aesthetics of painting.

I see this body of prints as opening an imaginative space for these issues. The psychological depths they evoke, while capturing the temporal and indexical trace of the performative act, for me strongly embody the tensions between form and content inherent to surface. So this ‘body’ of prints provokes simultaneity: in being at once indicative of the ‘real’ surface of the body while summoning subconscious realms.

- What is the significance of the mostly green colouration in your work?

I initially became intrigued with the colour because of how it could manifest absolute flatness with the printing roller while implicating depth through its relationship with water. The imprints of my body also leave a visceral residue – these greeny tones not only make me think of hospital wards but also the organic matter of the body – translucent areas of skin often take on a green-bluetone.

I also find minty and cream-soda greens evoke for me the fifties era, where many of the fundamentally modernist concerns discussed above reached an apogee, one that is nowadays being mined for the exciting possibilities of thinking about affect through form.

- Why is an art-historical background so significant, particularly, as we’ve discussed, in this body of prints?

I see my prints as drawing from a number of the ideas behind different factions of artists in the past century and which work to inform the kind of affects present in the work. One source could be that the prints evoke a strong Surrealist element referencing Hans Bellmer’s Poupeé series. Then there is also the reference to the history of the body as a performative implement: notably Jackson Pollock’s gestural brand of Abstract Expressionism. But then by making imprints of my body in a random and unplanned way, I’m also referencing the efforts of Robert Rauschenberg and Yves Klein, who wanted to negate the expressivity of the unique and ‘original’ artist completely. By drawing from all these conventions and the ideas they imply, I see new imaginative realms arising. In particular, I find these prints intriguingly evocative of Deleuze’s philosophy of becoming-animal.

- Is there a purposeful animalistic quality to the prints?

Rather than there being a strict ‘purpose’ to the affect of the prints, it was a quality that seeped into the work independently. Deleuze’s description of ‘becoming-animal’ as a one of the qualities or ‘logics’ of sensation in painting invokes, in his words, ‘…a pig spirit, a buffalo spirit, a dog spirit, a bat spirit’. This reading of affect seems uniquely apt for the strange shapes and forms produced in the prints, especially evocative for me in that they were completely spontaneous and based very much on the element of chance.

- The choice of skin-like media, such as oil paint and wax, can represent the surface of the body. As noted, here skin is literally the medium. Is this leap purposeful?

Yes, although thinking about the surface as skin can be seen as obvious, it affords a highly complex concept for thinking about surface, one that resists simplistic interpretations and instead focuses on the affective properties of materiality and form. I especially like how the notion of surface as skin in these prints causes a kind of double entendre – where skin becomes both literal and conceptual through the surface. Again, the tension between flatness and depth, form and un-form, manifests the skin-like boundary between ‘reality’ and the more subconscious realms of fantasy and beast. The slippage or breakdown between these tensions, as discussed, is in the fact that this is actual skin, as opposed to the metaphor for skin in most traditional works.

- Your wax painting, Planogram (2010), reproduces the effects of skin in a hyper-realistic manner, becoming an almost an archival object – this again plays with the tensions present in your work between conceptions of the ‘real’.

Yes, Planogram takes an opposite tack to the prints because the skin, although life-like, is evidently manufactured. However it is indicative of the topographical tensions present to the prints and I see it as a kind of ‘primer’ for viewing the prints. The wax has been worked over a piece of fabriano paper which is a slender support; the way in which it coheres to the paper and its resulting flexibility imitates a piece of leather or an actual piece of skin, sliced and sectioned from a torso. Because of this real fragility, the work has to be framed and exhibited in glass. However I see this limitation as evoking an archival or forensic preservation of a cadaverous object. Particularly in this work, I see a strong tension between the nature of its subject, as an object, and as a painted surface – like the prints, which confuse the boundaries between subject and object in the literal and conceptual use of the body.

The fissure opened up in the centre is furthermore evocative of the cracks or splits in some areas of the body, or it can be seen as some catastrophic event taking place on an abstract landscape. Then also, the conventional book format incited by the fold is at once figurative and abstract, and a direct invitation to the viewer to come and ‘read’ the sensations offered up by the surface, in all the works exhibited in the show, here quite explicitly suggested by the tensions between representation and materiality.

- Your current PhD research is based on a concept of trauma as it is related to these kinds of tensions evoked in your work. How do you separate your theoretical approach to trauma with trauma as a real aspect of life in South Africa – particularly as it has affected you?

My concerns, as I’ve briefly discussed above, are informed by the dialectics inherent to the structure and framework of much contemporary painting. In its theoretical form, trauma is a fitting concept for thinking in these terms, as in its most fundamental sense a kind of communication between personal (inner) and public (outer) spaces. But my interest in trauma as a concept is complicated, or indeed manifests a tension, in relation to the fact that I suffered the real trauma of being shot and left paralysed. Therefore thinking about where my real trauma, as a constantly felt disfiguring shock to the system, ends, and my practice, based on rigorous theoretical and philosophical concerns, begins – or where they intersect – is another source of interest which I engage with conceptually and philosophically. For instance, the prints can be seen to evoke an inner world of perceived deformation and detachment from the body, my body, as orderly and human. I hardly meant for this to come through in the work, but it did, while I was busying myself with all the other wonderful contradictions opened up by the imprinted surface.

- Many of the paintings for the exhibition include portraits – faces – which you determinably worked to exclude in the prints. What is your interest in portraiture and representation of the body?

I purposively omitted heads, hands and feet from the prints in order to elude the obvious relationship to the body and lay stress on the imaginative function of surface in its literal and conceptual guises. But with the ‘grid’ of portraits I again drew from Deleuze’s discourse of becoming-animal, here more particularly on his discussion of Francis Bacon’s paintings, where he speaks about Bacon’s surfaces manifesting animalistic ‘heads’ as opposed to human faces. I decided to explore the painted surface in this way, evading the more mimetic traits of traditional portraiture and instead focusing on the ambiguity manifested by the generally rough and spontaneous treatment of each square. These explicitly expressive gestural paintings serve as a kind of counterpoint to the prints – gesture as opposed to the inherent act of negation of autographic trace in the prints. Then as I said above, the prints in themselves bring to the fore this idea of opposition between the expressive mark and the index of the body by holding them in tension. From the grid of ‘heads’ to Planogram to the Skin Series, the invitation stands to immerse yourself in the affective fields of sensation and imaginative encounters offered by these surfaces.

Niall Bingham, who was the collaborating printer at the David Krut Workshop when this body of work was being created, wrote the following paragraph in October of 2010 regarding the collaboration with Webster:

“Jessica Webster arrived just after five, we planned to work after hours to avoid the embarrassment of nude confrontations with staff members. Jess wanted to work on a large format, so I marked out a full sheet of Somerset Velvet on the underside of the perspex covering the press bed. She decided to work in what she described as a “Chevrolet 80′s green”, a colour similar to the one she used for her smaller monotypes (Cadmium yellow, Thalo Blue R/S and black custom mix). I rolled out a slab of this colour, left the studio, and allowed her to roll in it. The ink was removed as it stuck to her skin. Depending on her body position the ink was removed in a variety of ways. Once Jess had reclothed herself, I returned to print, with the assistance of Thandi Phakedi, Jess’s sister. I’d like to think that Sigur Ros provided an appropriately moody atmosphere for the evening. We all enjoyed a lamb curry from Parker’s Grill for dinner, chef Gulam’s speciality. Jess returns on Friday to resolve the images, fully clothed.”