ROMANCING THE PLATE

by Rosemary Simmons

The evolution of William Kentridge‘s new intaglio plates from

PRINTMAKING TODAY Volume 2, No.4, Winter 1993 by Rosemary Simmons, Editor.

Johannesburg formed William Kentridge and it remains his home base, yet his vision and work have universality as well as a multi-media approach.

He has just completed an intense short period of working with Jack Shirreff at 107 Workshop in Wiltshire finalizing plates and editions from two previous visits in the last year.

Meanwhile his theatrical presentation of “Woyzeck on the Highveld”, with actors, puppets, music and projected drawings played in London, and at the theatre festivals in Munich, Antwerp, Leeds and Zurich.

Searching for a short word to describe him, “polymath” seems suitable: one who knows many arts and sciences. He majored in Politics and African Studies at Witwatersrand University, meanwhile starting a theatrical company. Then he went on to study art at the Johannesburg Art Foundation where he developed an interest in printmaking.

He later taught etching at the Foundation and rounded off his formal education by studying at the Ecole Jacques Lecoq in Paris.

His first solo exhibition was while he was teaching etching; soon after which he developed a way of making animated films that are an unusual synthesis of his previous drawings which are altered shot by shot rather than the usual cel animation which requires a new drawing for every frame of the film.

A strong narrative line runs through these films; acerbic satire of life in South Africa predominates. As his characters interact so the drawings are altered. There may be no more than a few dozen drawings used in an eight minute film; these, however, could have been modified and filmed up to 500 times each.

It is something in this transformation and discovery which finds a familiar response when working on intaglio prints with Jack Shirreff. Obviously, there is the pleasure in collaboration, the sparking of ideas with like minds, but it is also the belief in letting the medium play its part in the final outcome.

You may start with a charcoal drawing of an iris flower but at some stage the copperand acid or the acrylic sheet and the engraving tools impose their own senario much as characters in a play or film.

I think it is what William Kentridge welcomes and allows.

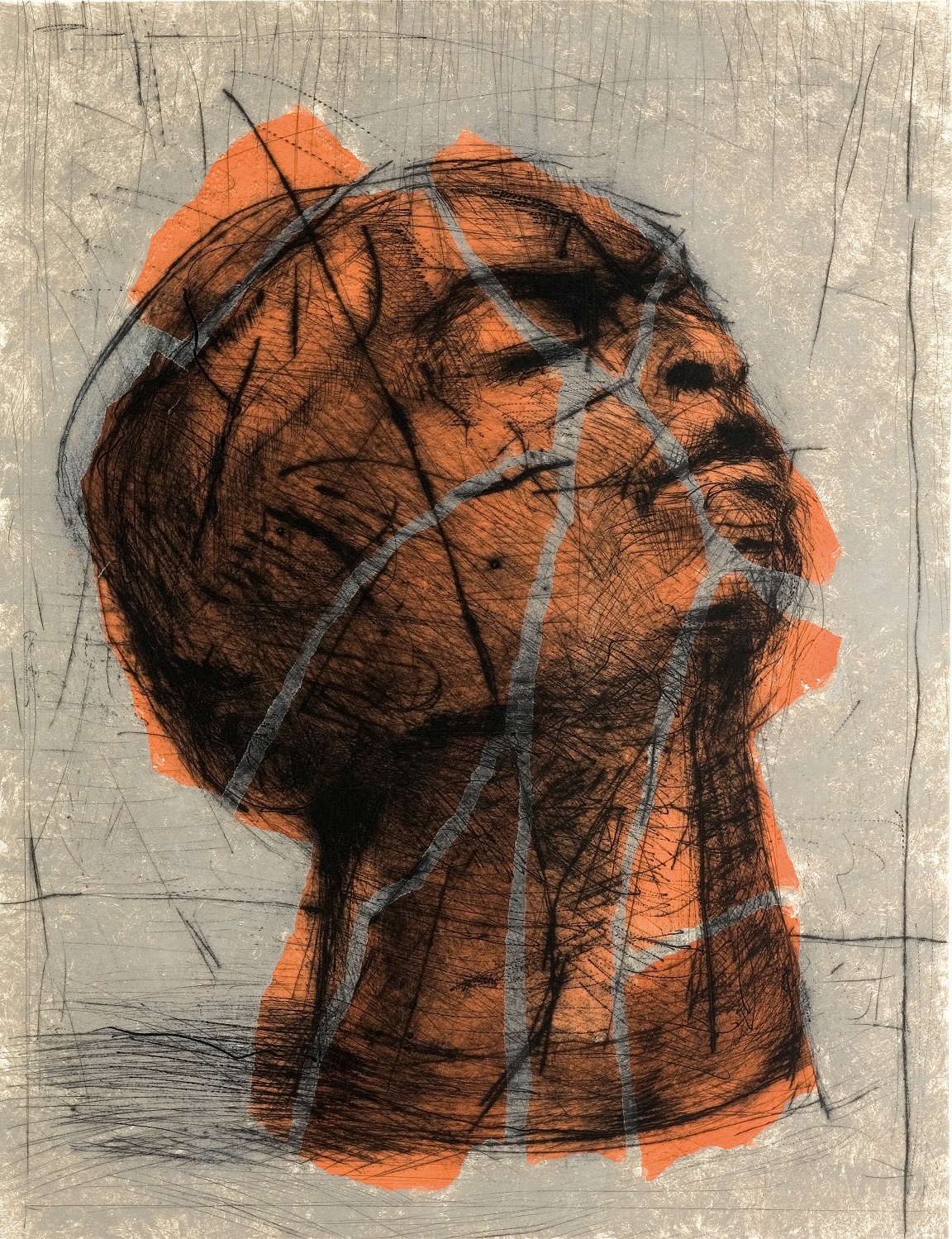

Two of the recent prints GENERAL (1993), and HEAD (1993) seem to relate most directly to the animated films, and to Kentridge’s adaptation of Woyzeck.

This play by George Buchner, first published in 1836, is now known for the opera by Alban Berg, completed in 1921. It tells the story of a simple soldier persecuted and put-upon; more tragically than in “The Good Soldier Schweik”, but equally harassed by superiors.

Kentridge moves the story to a mining compound near Johannesburg and uses one actor to speak for each not-quite-life-size rod puppet (designed by Kentridge) and another to manipulate the arms and mouth mechanism.

The print of the GENERAL evolved from WOYZECK ON THE HIGHVELD via the computer animated film EASING THE PASSING OF THE HOURS.

It is basically drypoint on acrylic sheet printed on to pre-painted paper. Kentridge sees this as a monoprint as each background painting is different.

This is one of the benefits of printmaking because variations can be made while still keeping the essential matrix unaltered. One could, of course, choose one trial image and prepare background plates for normal editioning.

HEAD is also drypoint on acrylic giving an effect not dissimilar to Kentridge’s charcoal drawings. He then took torn paper shapes which were inked in orange and laid on an acetate sheet in position – this provided a second colour giving shape to the contours of the head.

It was printed first in the final edition. Kentridge likes engraving into acrylic, not only because he can work fast with all manner of tools, but because the transparency of the plate has numerous advantages for laying on top of drawings and proofs

His other recent prints are distant from the anxieties of his distant land and, perhaps, represent a need to affirm the natural beauties of the world even though that world is in a political turmoil.

IRIS is also a drypoint on acrylic, with a torn paper plate and a further hand-coloured plate. The iris is many times larger than life with rich colouring making a very powerful image.

The next iris, DUTCH IRIS 1, is by contrast a single copper-plate liftground aquatint with multiple colour inking a la poupee.

David Krut, who is publishing these prints, says it has “a spacious Japanesy feel” rather different from Kentridge’s drawing-bound prints.

“I decided to publish this state because it shows William Kentridge’s skill with a brush and Jack Shirreff’s lift-ground aquatint skills as well”. It is equally large and impressive.

DUTCH IRIS was conceived by Kentridge as a four plate print: drypoint on acrylic and three aquatinted copper plates. DUTCH IRIS 1 was a bit of an indulgence as it was never contemplated as a print in its own right.

DUTCH IRIS finally ended up as the black printed acrylic plate, printed between the two lift-ground aquatints like a sandwich.

This formula was arrived at after much proofing, wet on wet, and many colour trials: it is now awaiting editioning and will be published in 1994. The result is a most dramatic image which has all the dynamism of drawing with all the painterly qualities of rich colour.

These prints use the medium of intaglio not just as a means of replication but as a medium of such flexibility as to rival painting.

They grow to fruition because of the medium; they developed because it was possible to proof any number of variations and yet not destroy the matrix (as Kentridge did when erasing and changing his animated drawings).

They also came to fruition because of the extraordinary sensitivity of Jack Shirreff and his colleagues who have every technique at their fingertips and yet know how to draw back and allow an artist space to develop his ideas.