I have always had some misgivings about the sea. These misgivings are more or less the same when someone speaks to me of the ocean. Or not less, but there are differences between the misgivings I have of the sea and the ocean. When someone speaks to me of the ocean I think of much wider expanses of sea seen from a plane or satellite photographs of the earth. Here the ocean gives contour to continents with flats expanses of cerulean blue between. Shadowy darker blue dots certain places; we are told that some of these places are so deep that they have never been visited by man. Man has achieved higher altitudes than deeper depths, as far as our position on earth is concerned.

From a high viewpoint or a satellite photograph these deep areas look like shadowy ink blots and the flat expanses which span continents can be measured between my fingers. From where I am the truth of the ocean is an utterly different thing. I have to imagine how far the flat expanses stretch and how deep the deepest canyons hollow. The responsibility for this imagining is as big and serious as the ocean, and this causes me some misgivings, because I am bound to leave something out. That something I leave out unnerves me, because there is a sense, isn’t there, that that something may be the most important thing. The sea, as it is a part of (but different from) my image of an ocean, gives me a similar ambiguous sense. I am missing something important. This thing causes me to have misgivings.

To visit the seaside and spend time on the beach is a common pastime of my childhood. To name but a few busy activities, clutches of seashells that smelled shelly, and a big blue sea the colour of my eyes in which to swim like a dolphin, and a mermaid, weightless, dipping and diving, bright water. The sand both grated and smoothed against my skin; it left tiny crystals glittering all over my arms and legs and in my hair. I still love the smell of salt and sun and plastic buckets and sunscreen. But I do not love the sea.

From the porch of my parents’ seaside cottage the view out to sea is high enough for the press of the ocean. If I place an image of myself standing in front of where I sit on the porch, the ground stretches just to the point below my kneecaps. Just behind my kneecaps, rocks and swirls of white foam spoil each other. But from the base of each kneecap stretches upward a large expanse of sea which folds over the top of my shoulders, cutting off my neck and head, which are lost in the clouds. The sea is the trunk. If I place an image of myself standing in front of where I sit, I am truncated by the sea such that the sea is my trunk. The trunk is, as we all know, the place where all the meaty stuff is set. It is set there in the trunk in such a way that it can remain largely inert and unaffected by the sweeping actions of the limbs. The meaty stuff – organs that have functions operating in symbiotic rhythms – have their own life independent of your best friend, of a movie on a Sunday evening, of a call from your mother, even with a steak and chips at a sports bar on a weekend hangover. To be sure, what you eat affects the machinations of the organs but these are affected by whatever you eat – it has value for the level of nutritional substance provided but otherwise your trunk has no time for meaning whatsoever. It is only truly affected by the desires violence in man and rollercoasters.

The sea is largely the same. There is an original dependence on the sea for the functioning of life. We plumb its depths for oil to make our rollercoasters faster and our guns penetrate deeper. We fish all sorts of fish so that someone with pertly held chopsticks and neat ankles can say ‘I luurve sushi!’ We ride its shoreline peaks with long and short, body, knee, and kite boards all carefully rubbed with beeswax. If you are carried along by a wave towards the shore you feel very comforted and loved by the brilliance of your wave, as if you are in togetherness, working in concert to achieve an aim of riding, as if on a rollercoaster. Here nature is kind and supportive of your desire to be held, to be carried swiftly, lovingly. When you are being drowned by the sea in a tidal wave or undercurrent, you feel as if the sea holds something terrible against you, nature has colluded in air and water to put you precisely in the spot that sucks you down against your will. Nature is wild and unkind.

People say, ‘I love the sea,’ and, ‘I am happiest when I am near the ocean,’ and other things that assert an attachment to these waters. It asserts a value of connectedness to this most primordial form of nature, the origin of life. People feel humbled by this awareness and via this connection feel themselves to be humble. They assert this humble attachment by pronouncing it to others. But even as we view the sea humbly and acknowledge with gravity the ocean beyond it, the sea lives on without regard for our thoughts. It pulls and pushes its mass, churns and whips along. The sea does not love or hate, it has neither love nor hatred in any of its parts, if indeed there is anything of the sea to partition.

In lieu of the contradiction the various gifts the sea can bestow, some people will say with a knowing face, ‘You need to respect the sea.’ But the sea has no time for respect. Love, hate and its middleman respect is meaningless to the sea. The sea and the ocean want nothing of us. You cannot measure a regard for the sea between your fingers, or in statements that bounce off the surface of the water not even to echo back at you. We can only measure our regard for the sea with respect to the regard held by others (even if in this regard they are drowned); the sea has nothing to do with it

This clean cut between you and the sea, between me and the sea, requires a degree of imagination in crossing over from where I am writing, a crossing that can take us to the sea. But this degree of imagination, where it takes the form of deciding on your love or hate for the sea, misses something essential when we take into account that the sea has no time for love or hate. Is there a form of imagination free from love and hate? Kant would refer to it as the ability to judge pure beauty; psychology calls it the depressive position.

Others, many others, have found a satisfying form of crossing to the sea by documenting in precise detail all the empirical data to be had of the sea and can therefore largely shrug off the weight of the sea in imagination. They document how far the sea stretches from bay to bay, how the sea is the ocean by dint of its precise location on a carefully detailed map, how deep its crevasses hollow, how high its mountainous ridges rise, how much water that is seawater weighs, why it is so salty, a measure of the strength of its tides, precisely what type of creature lives in which salted waters, what type of person lives off what sea creature, what type of person has access to certain parts of the sea, what happens when certain people fish in precisely dangerous areas. We have a lot of data on this issue of the sea, and it ranges all over, and it is imbricated in complex structures. The sea goes on oblivious.

People come and watch the sea. People lay down blankets and towels, tents and umbrellas, and day after day they sit and watch the sea, or at least it is a European fashion to congregate at the sea in this way. But people, as a universal principle, as much as they are in proximity to it, look out to sea.

I have a past, a collection of memories attached to my sea in one hand. In the other hand, I have a vast array of scientific data about the sea. Between these, there is only my trunk, which, much like the sea, carries on churning and grinding regardless of what I hold in my hands. The trunk is what is left when I have sifted all my memories through my fingers, when I pinch large granules of data between my fingers and allow the finer grains of no concern to escape. Yet the trunk is a large area to call a remainder. It escapes my sifting and sieving, because it has no interest in the actions of my hands. It is absent from the entire process.

People stop at car accidents and they watch the sea.

– Jessica Webster, 2012

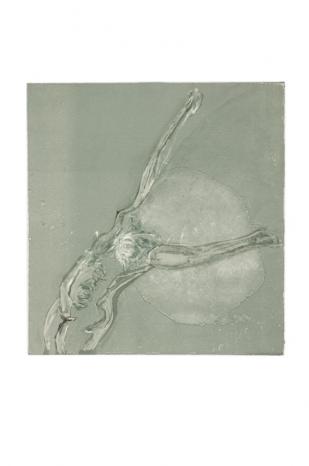

IMAGE:

Jessica Webster, Swimmer 2 (2010), monotype.

This text was produced by Webster in conjunction with Cross-Currents, a group exhibition in which her work is included, showing at David Krut Projects Cape Town, 31 July – 25 August 2012. Cross-Currents presents a selection of works that draw on ideas of the sea, literally – as in, how do we relate to the sea and how have we related to it over time – and metaphorically – what does the sea stand for and how do we extrapolate the psychological implications of the idioms that we’ve developed around the ocean.

See also Cross-Currents – Lien Botha writes on The Sea

Jessica Webster was born in Johannesburg in 1981 and grew up near the mines of Durban Deep in Roodepoort, before relocating to Benoni. Webster obtained her BA degree in Fine Arts from the Michaelis School of Art at the University of Cape Town, where she was awarded the Judy Stein Painting Award in 1997. The artist completed her Masters of Fine Art and embarked on her PhD in 2011.

Webster’s debut exhibition I Knew You in this Dark opened at David Krut Projects in July 2009. She was also one of the artists that participated in the group show DKW Monotype Project at the DKW gallery in October 2010. Webster’s second solo exhibition called Original Skin ran throughout the month of April 2011 at David Krut Projects, Johannesburg. After completing a residency at NIROX Foundation later in 2011, she was invited to exhibit at NIROX Projects at Arts on Main in 2012. The exhibition was called Mainly Benoni. And Paintings