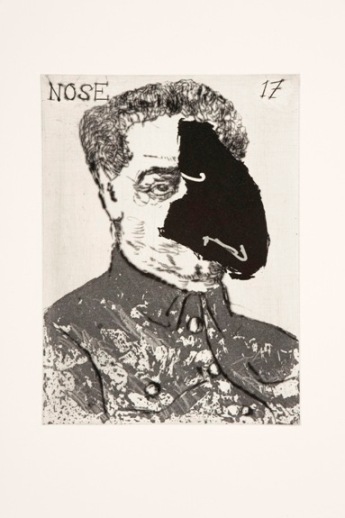

Nose 17

BAD DISGUISES 2

In the 1920s, Trotsky was airbrushed out of all photographs that showed him with Lenin. We are by now so familiar with this emblematic erasure of history that in all the group photos of Soviet luminaries, we look for or anticipate the absent figure in the crowd, a spirit of Elijah, at the table but invisible. We glance over the rows of sleek faces, but are entranced more by what or who is not there than by what we see.

Airbrushing is time-consuming and a real art, and so, for the most part, when members of the Party were purged and their images proscribed, their faces were eliminated from photographs by being scratched away or defaced with ink or paint.

To remove an image or part of it from a copper plate involves physically scraping away the metal until the metal is flattened down to the depth of the line you want to remove. This involves the use of a sharp triangular tool, considerable knuckle strength and dexterity, and hard calluses on your index and middle fingers. The plate is then polished with a burnisher, a rounded smooth tool—with the same finger requirements as the scraper—to eliminate the crude marks of the scraper. But the burnished plate will now print a clean white, so the surface must be disturbed again if it is to regain the grey plate tone of the rest of the plate. I usually do this with sandpaper, the coarseness of the grit on the paper determining the depth of the plate tone. A really good etcher or engraver can make the history of this erasure invisible. I have neither the skill nor the patience for this, and reconcile myself to the claim that I prefer the plate both to contain its history and to reveal traces of it in its printing.

This text by William Kentridge appears alongside the illustration of this print in William Kentridge Nose: Thirty Etchings, edited by Bronwyn Law-Viljoen and published by David Krut Publishing in 2010.

Nose 17, Nose 18, Nose 19, Nose 20 and Nose 21 form a miniature narrative of their own within the suite of etchings. Each print is a portrait with the face of the sitter removed in some way. In his text for each print, Kentridge provides information about who the sitter could be, although the face is not visible, playing on the common practice of erasing people from photographs that Kentridge refers to in the text for this print.

| Artist: | William Kentridge |

| Title: | Nose 17 |

| More about: | William Kentridge (Nose) |

| Year: | 2008 |

| Artwork Category:: | Editions & Multiples published by David Krut |

| Media & Techniques: | Drypoint, Engraving, Sugarlift Aquatint |

| Edition Size: | 50 |

| Image Height: | 35 cm |

| Image Width: | 14.9 cm |

| Sheet Height: | 40 cm |

| Sheet Width: | 35 cm |

| Framing: | Unframed |

| Artwork Reference: | 1221 |