Artworks Selection: The Universal Archive

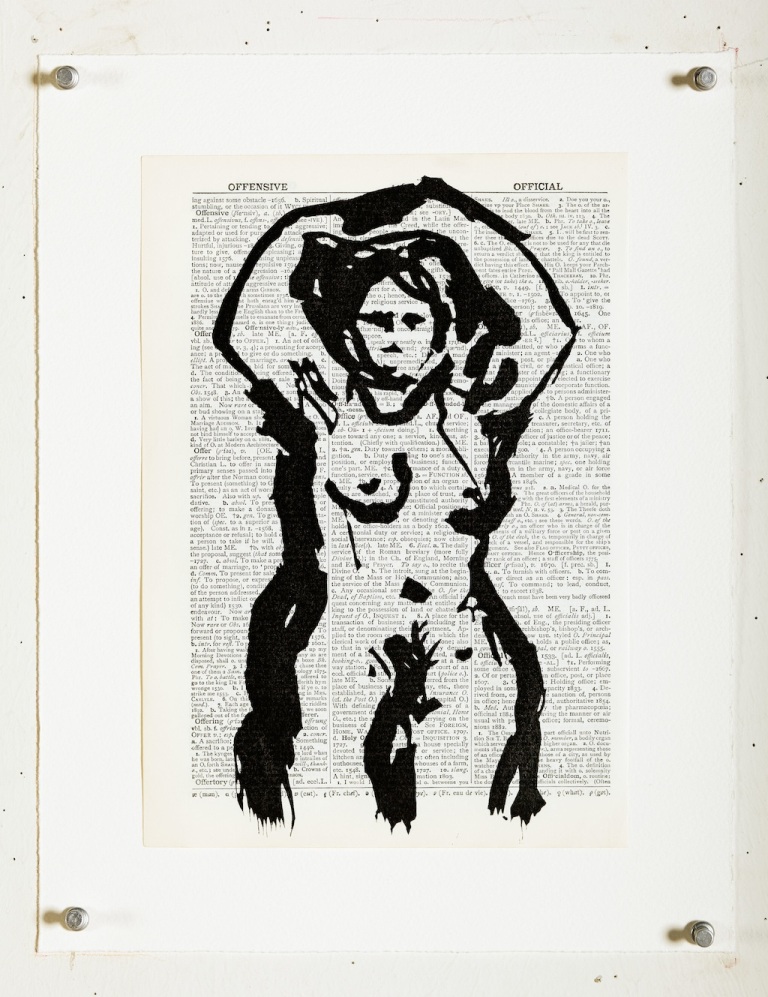

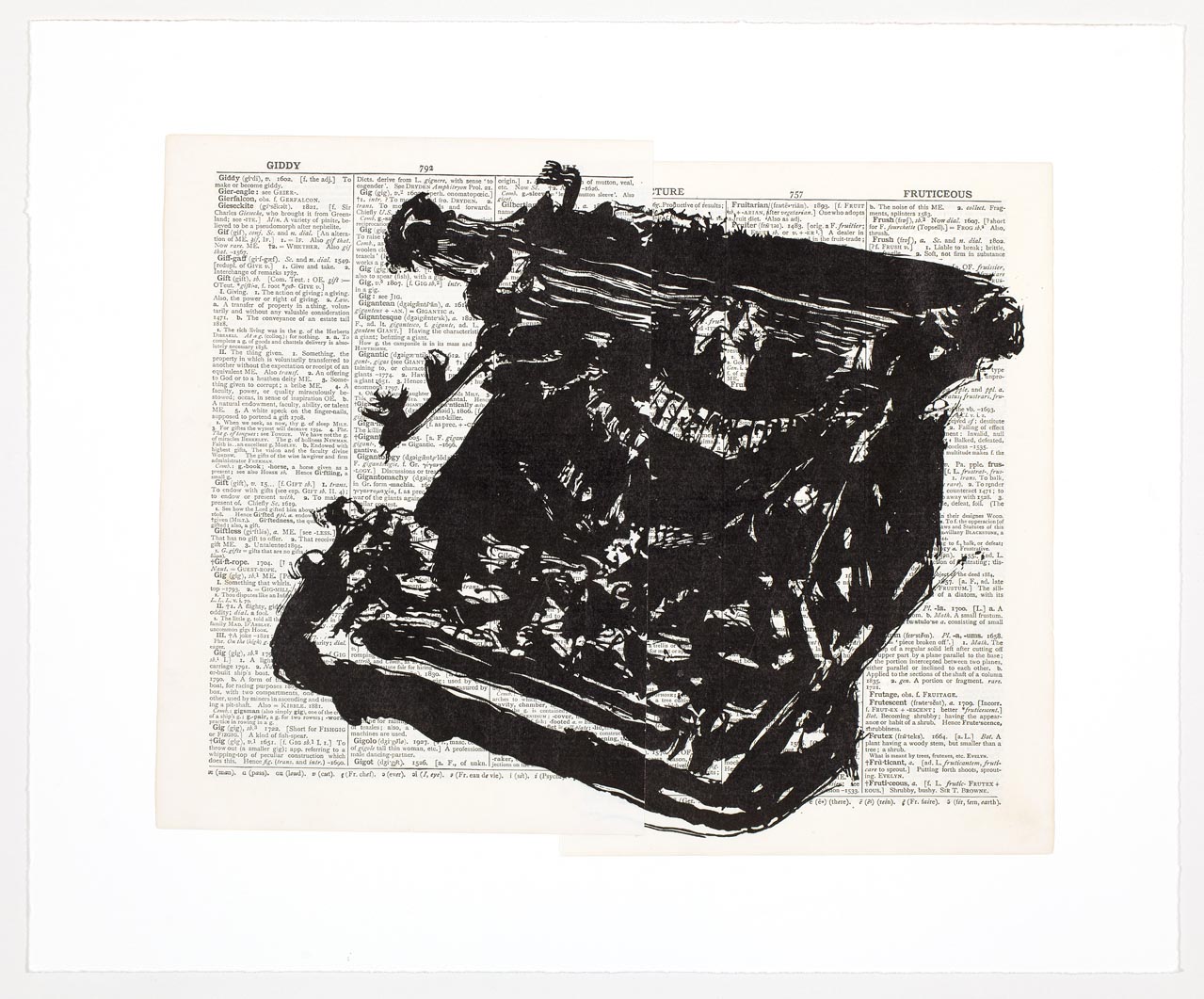

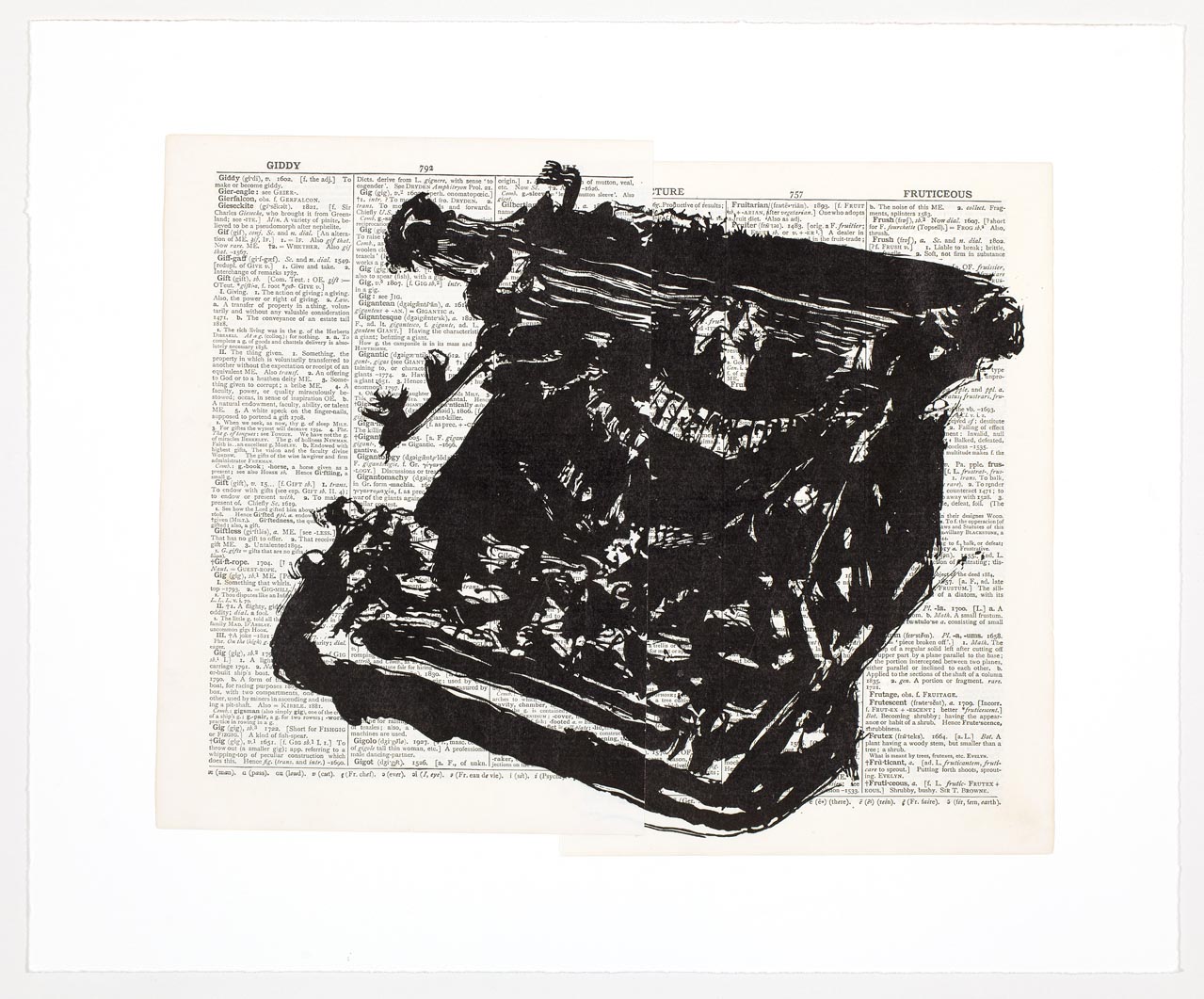

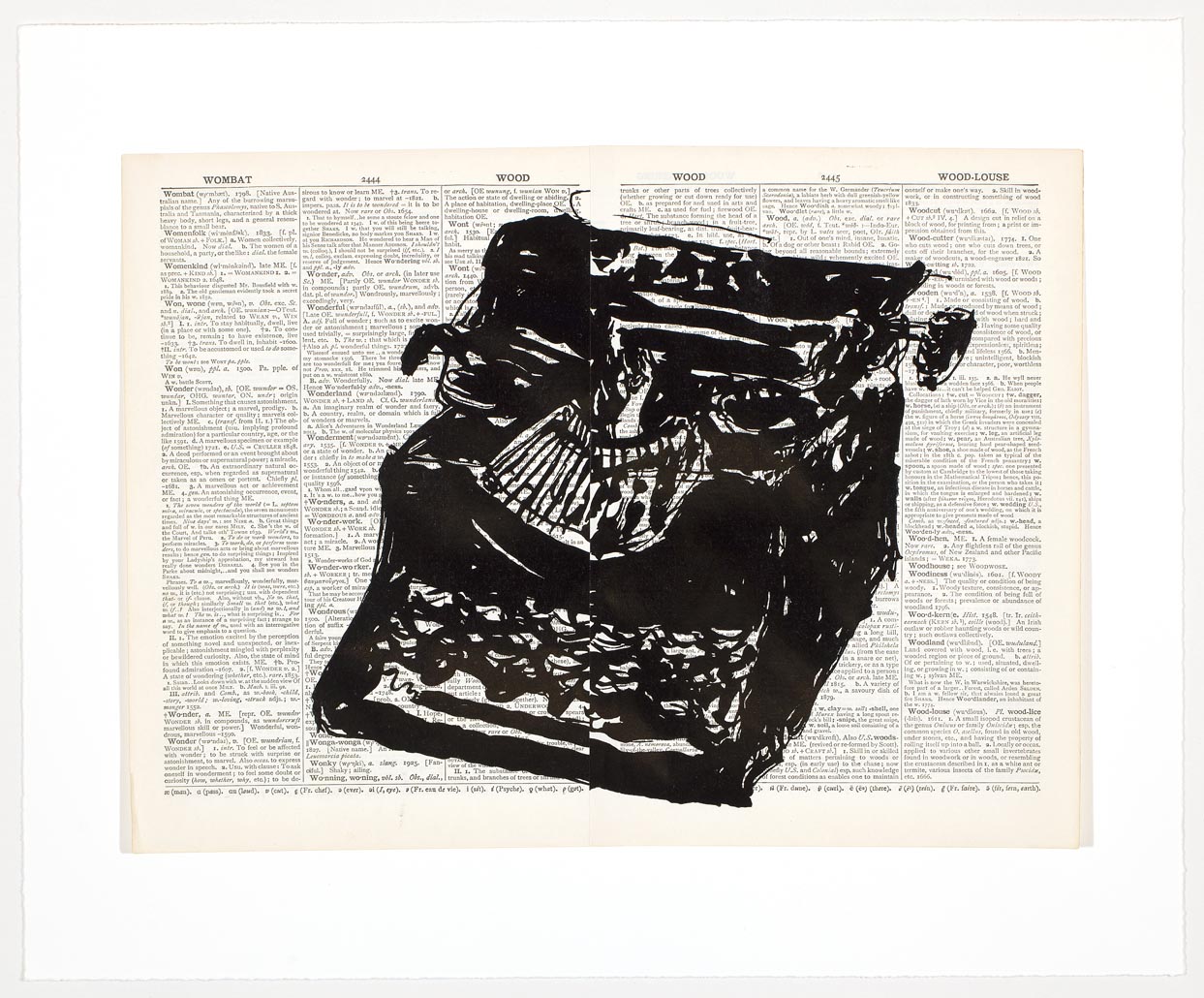

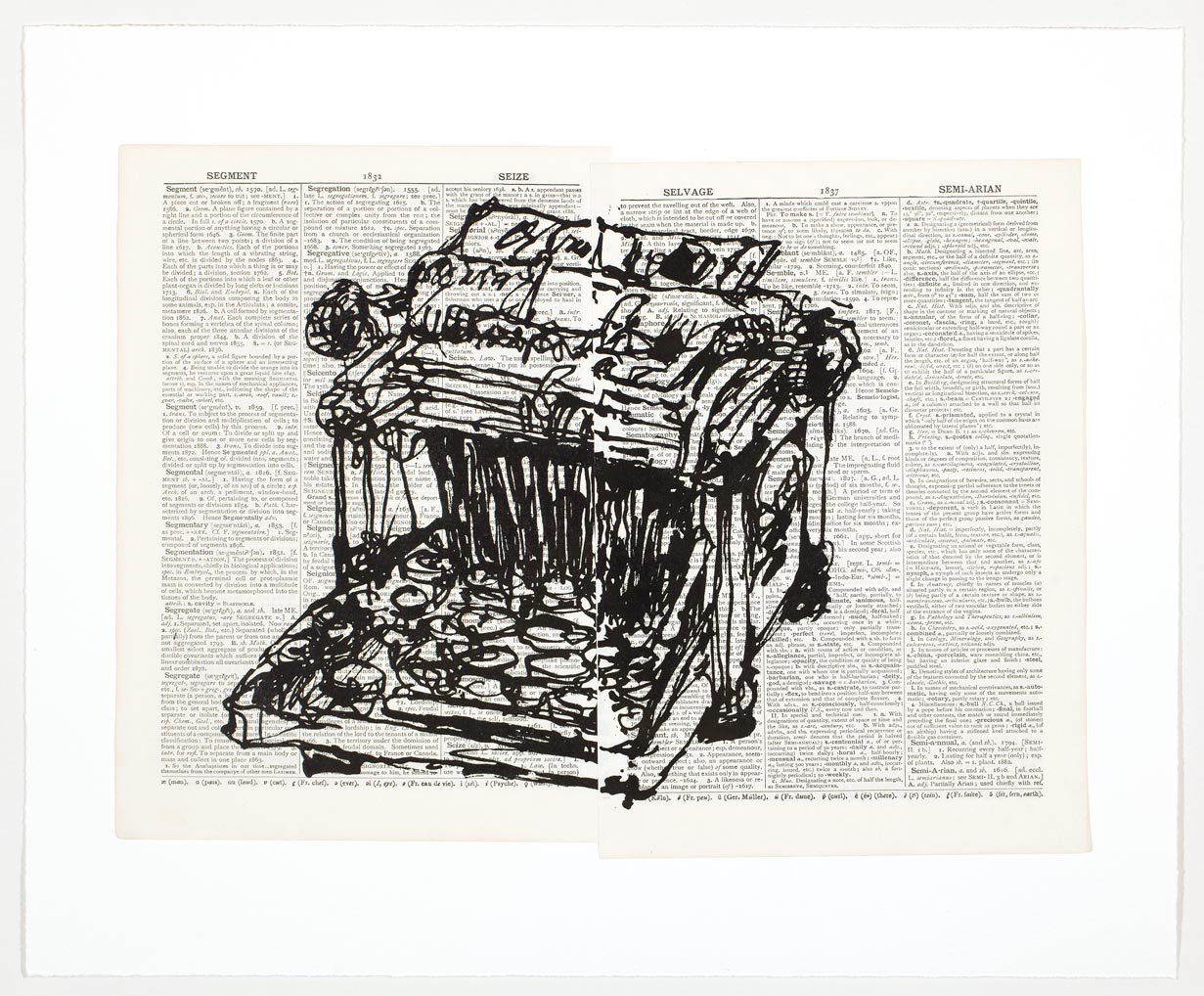

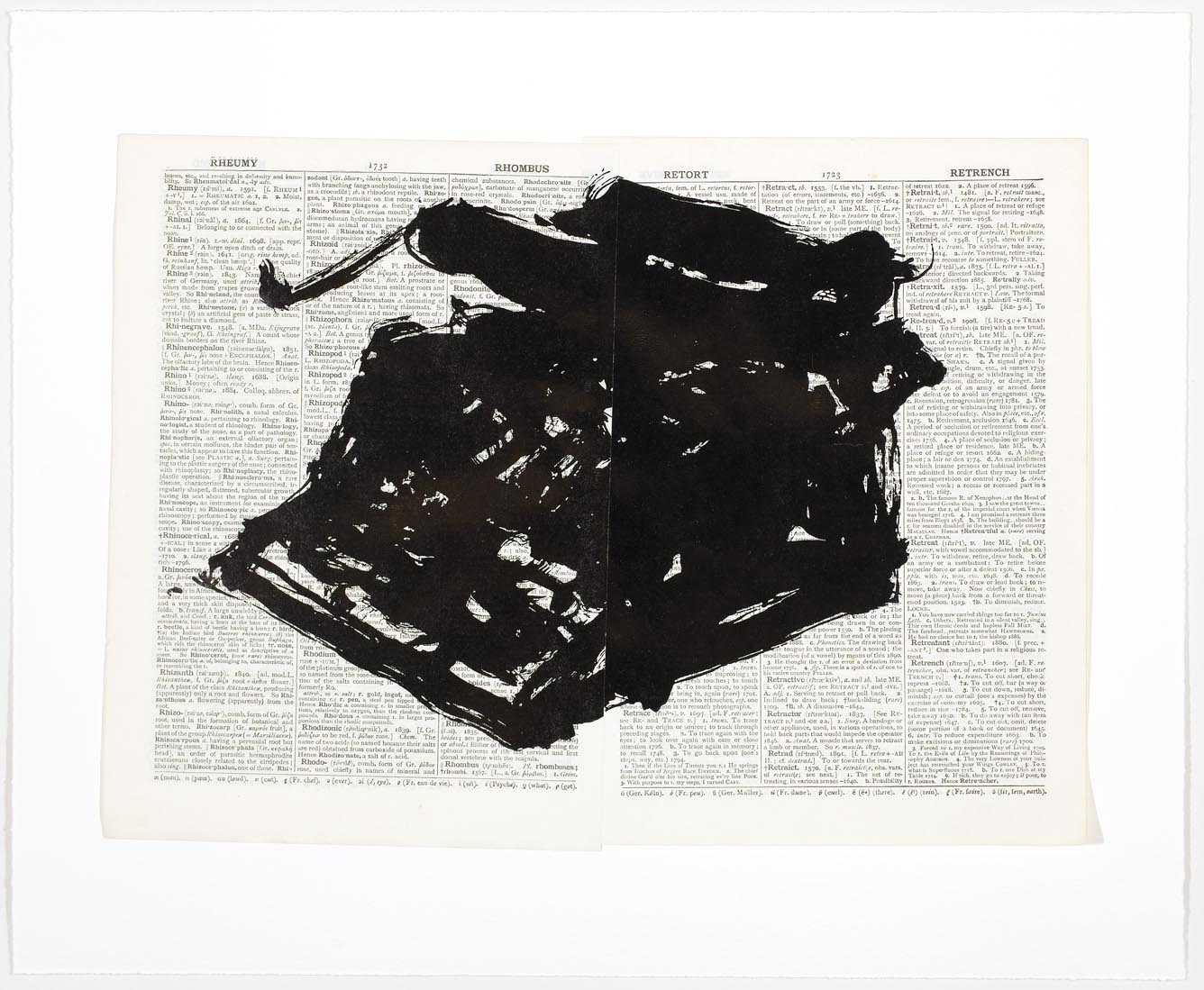

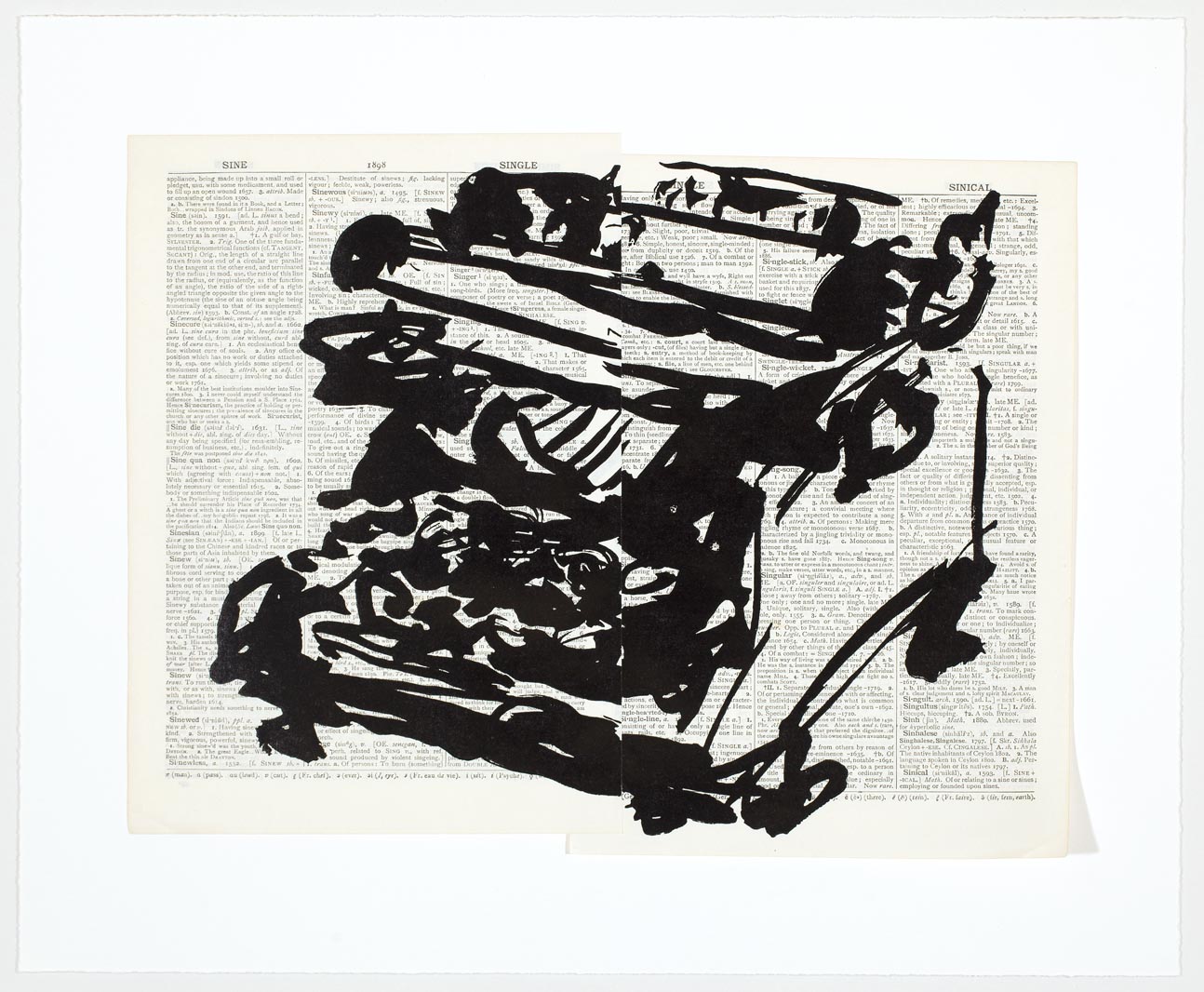

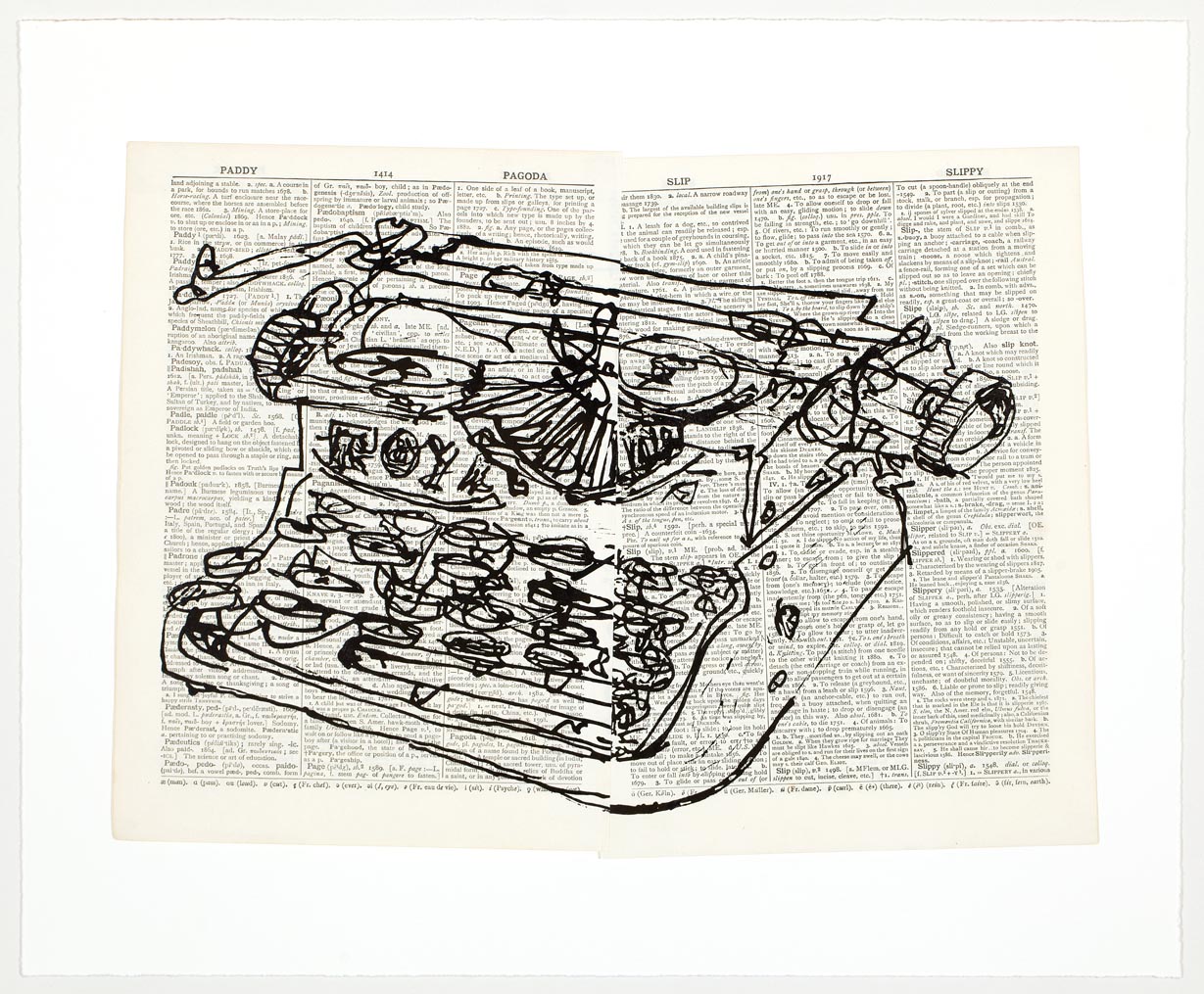

The Universal Archive began at the David Krut Workshop in 2012 and is made up of linocuts printed onto non-archival 1950s dictionary and encyclopaedia paper. The series contains over 70 individual images. Many of which represent recurring motifs commonly seen in Kentridge’s art, ink drawings, sculptures and stage productions. They depict everyday images, such as coffee pots, trees, cats, female nudes, typewriters, horses and birds.

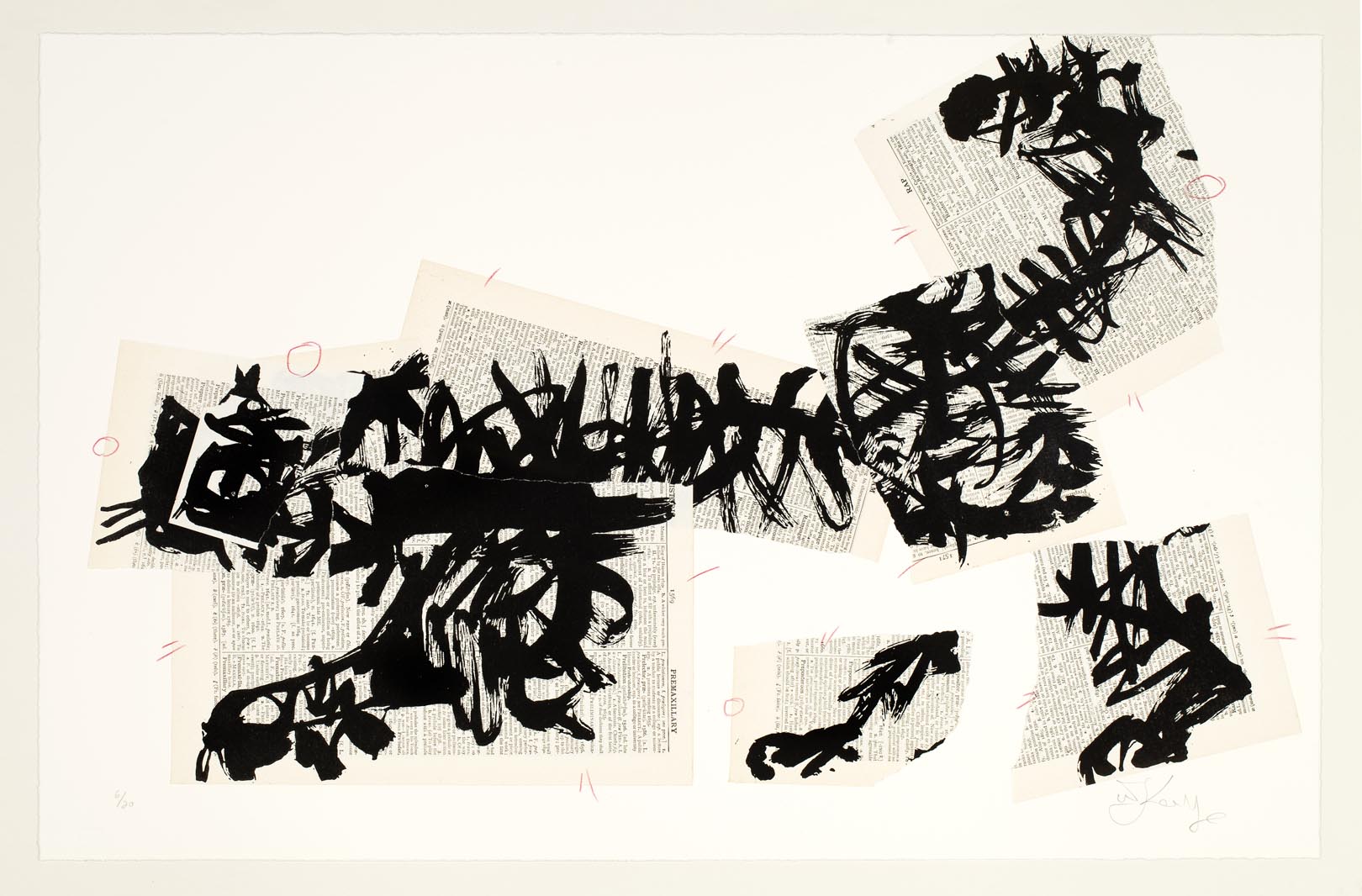

The Universal Archive linocuts began as a series of small Indian ink drawings, created in a state of what Kentridge refers to as “productive procrastination” during the time that he was preparing his Norton series of lectures, presented at Harvard University in 2012. The drawings were made on pages of old dictionaries, using both old and new paintbrushes. The former refers to the pristine new brush, which gives perfectly intentional lines. The latter has damaged, splayed bristles which gives a less certain mark. It is the worn, mistreated brush that artists tend to discard but Kentridge embraces for its individual qualities. Hence, the images are made up of both solid and very fine lines, with an unconstrained virtuosity of mark-making. The ink drawings were initially attached to linoleum plates and painstakingly carved by the DKW printmakers and the artist’s studio assistants. Master Printer Jillian Ross speaks of the exacting process as “a giant puzzle constantly solving”. As the project expanded, the images were photo-transferred to linoleum plates in order to preserve the original drawings. The images have been printed onto pages from various books, including dated copies of the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary and Encyclopaedia Britannica.

The use of dictionary pages for this project is both unusual – considering the paper’s non-archival qualities – and significant – in terms of the manifold associations that spring up within each work as a result of the spontaneous overlap of image and text. The philosophical implications of this choice have been expounded superbly by Kentridge, in a publication produced in collaboration with Jane Taylor:

“A dictionary is not the same size as a head, although it is quite close, and the thousands of pages in the dictionary do not even begin to match the uncountable number of thoughts, associations, flashes of ideas that zoom around inside the head. But nonetheless there is something of the weight and pages enclosed within the covers of a dictionary that has an association with the memories, the thoughts, the knowledge of different kinds, that we have inside our heads. And the drawings on the different pages of the book do not try to give a map of the way they think, but rather put a marker for the processes, unpredictability and marvels of association that we produce in our heads all the time.”

As a result of the meticulous mechanical translation of a gestural mark, the linocuts redefine the characteristics traditionally achieved by the medium. The identical replication of the artist’s free brush mark in the medium of linocut makes for unexpected nuance in mark, in contrast with the heavier mark usually associated with this printing method. Furthermore, the paper of the nonarchival old book pages resists the ink, which creates an appealing glossy glow on the surface of the paper.

Many of the images are recurring themes in Kentridge’s art and stage productions: cats, trees, coffee pots, nude figures. While some images are obvious, others dissolve into abstracted forms suggestive of Japanese Sumi-e painting. Image mis/identification is core to Kentridge’s practice and is richly explored in this series. The parallel and displaced relationships that emerge between the image and the text on the pages relate to Kentridge’s inherent mistrust of certainty in creative processes. This becomes part of a project of unraveling master texts, here questioning ideas of knowledge production and the construction of meaning. Aside from the numerous individual images created, there are prints assembled from pieces: cats torn from four sheets, a large tree created from 15 sheets. Groups of prints featuring combinations of individual images – twelve coffee pots, six birds and nine trees – show the artist’s progressive deconstruction of figurative images into abstract collections of lines, which nonetheless remain suggestive of the original form. The process by which the viewer projects meaning is sincerely rattled. This movement from figuration to abstraction and back, along with the works’ close relationship to Kentridge’s stage productions, suggests that this body of work holds an intriguing place in Kentridge’s oeuvre on the edge of animation and printmaking.

Ross, who has worked with Kentridge since the early 2000s, stresses that an in-depth understanding of the series requires knowledge of the multiplicity inherent in many of Kentridge’s projects, in which the same imagery recurs in varying forms. “Because he often works on a number of projects at once, his ideas for one project tend to fuel another. Images that you see in Universal Archive overlap considerably across many mediums.” Ross adds that she sees the title as “a reference to his personal ‘universal archive’ – the themes and images that he repeatedly draws on to animate his work.”

Text by Jacqueline Flint, 2020

Universal Archive-Ref. 64 (ed. of 15)

Universal Archive-Ref. 63 (ed. of 15)

Universal Archive-Ref. 62 (ed. of 15)

Universal Archive-Ref. 61 (ed. of 15)

Universal Archive-Ref. 60 (ed. of 15)

Universal Archive-Ref. 59

Universal Archive-Ref. 58

Universal Archive-Ref. 57 by William Kentridge (Universal Archive)

Universal Archive: Ref. 21 Version E

Horse