by Harry Inglis, NY

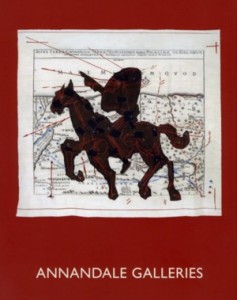

To complement their current exhibition of William Kentridge’s works entitled, Telegrams From The Nose, the Annandale Galleries of Sydney have produced, under Anne Gregory’s guidance, a marvellous book-cum-catalogue, of the same title, which serves as both a handbook to those attending the exhibition, and a valuable read in its own right.

The book showcases quite a breadth of Kentridge’s artistic production – from sculpture to drawings, etchings, tapestry, and even shots of his stereogravures – but opens with a perceptively biographical piece written by noted critic of the Sydney Morning Herald, John McDonald. McDonald faithfully depicts Kentridge as an artist whose intimate creative outpouring and whose appreciative audience is both “international and intensely localized”. McDonald intimates that Kentridge’s art is one that transcends dichotomous barriers, whether those that exist between past and future, private and public, or even truth and deception. It seems evident from McDonald’s exposé (although he does not say so explicitly) that Kentridge has been in the wonderfully fortunate position of riding a wave of strong post-colonial social and artistic sentiment which quite naturally found one of its most effective forms in the acerbic ‘struggle’ art of the apartheid period in South Africa. However, McDonald projects a level of interpretation which recreates Kentridge as a didactic artist – one who seeks to draw “political and moral lessons” from which we, the viewers, are ostensibly intended to draw conclusions and internalize them as a form of conceptual mimesis.

The book gives us a broad sense of Kentridge’s aesthetic variability which is mesmerizing to say the least; with unerring talent he flits from etching to sculpture as easily as politicians in “The New South Africa” defect across the parliament floor as it suits them. The director of the Annandale Galleries, Bill Gregory, also gives some insight into the reality of Kentridge’s creative experience. He details his visit to the Kentridge house in Johannesburg in preparation for the opening ofTelegrams From The Nose, and shows Kentridge to be a consummate artist but also a person of great empathy and certainly what some might call a polymath with his wealth of talent and breadth of interests. Gregory is correct in surmising that Kentridge’s real power lies in his ability to reveal the pitfalls in representation and our concomitant weaknesses with perception and, therefore, what we believe to be true and obvious. We are often lured as willing participants into Kentridge’s work by an arcane beauty, one which moves us like that of Gericault or Gentileschi, but then find ourselves confronted with unexpected dimensions or deceptive surfaces of expression. Every work brings something different to appreciate but, like the work of all great artists, keeps us tethered to a thread of aesthetic constancy that is undeniably Kentridge’s own. Gregory suggests that “How People See” could be the subtitle of the show. And indeed, given the various written pieces and the images in the book, the book itself could be subtitled “How People See William Kentridge”, and I think that it is this ‘in-the-round’ biographical approach that the Annandale Galleries have taken in the book that is the book’s greatest strength in its attempt to portray such an interesting artist and human being.