By Jessie Cohen

21.04.16

To coincide with the hotly anticipated opening of Triumphs and Laments – a 550m frieze on Rome’s Tiber embankment by William Kentridge – David Krut Workshop (DKW) have collaborated with the artist to make a woodcut drawn from this very project.

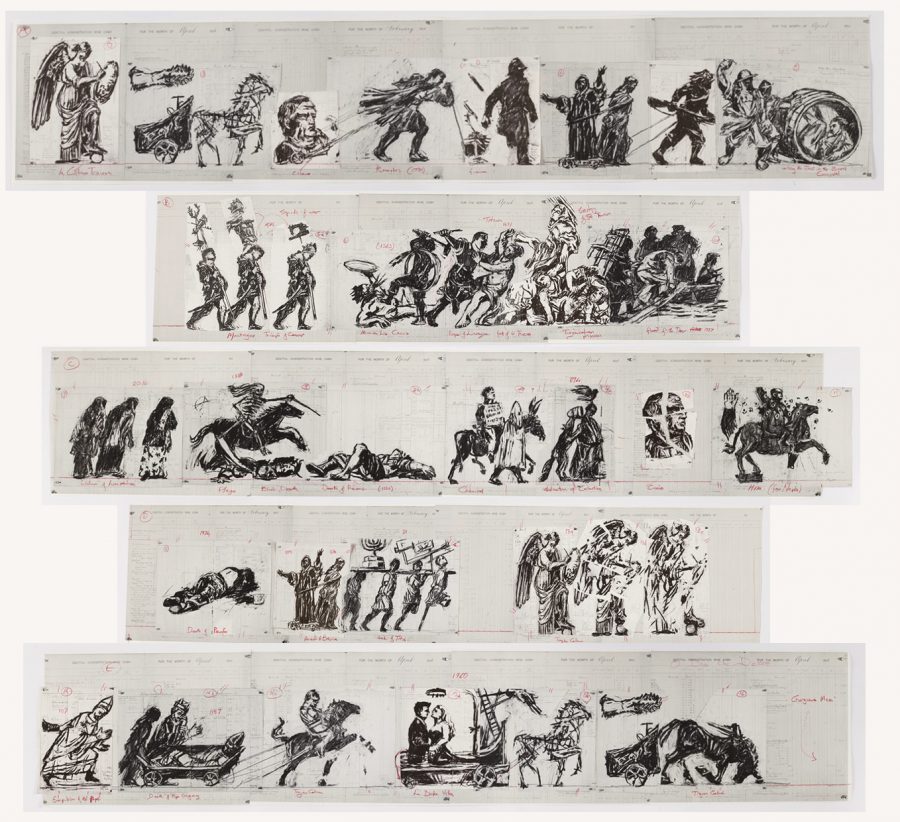

Triumphs and Laments consists of eighty figures, up to 10m high, selected from Rome’s rich political and cultural history from ancient to modern times.

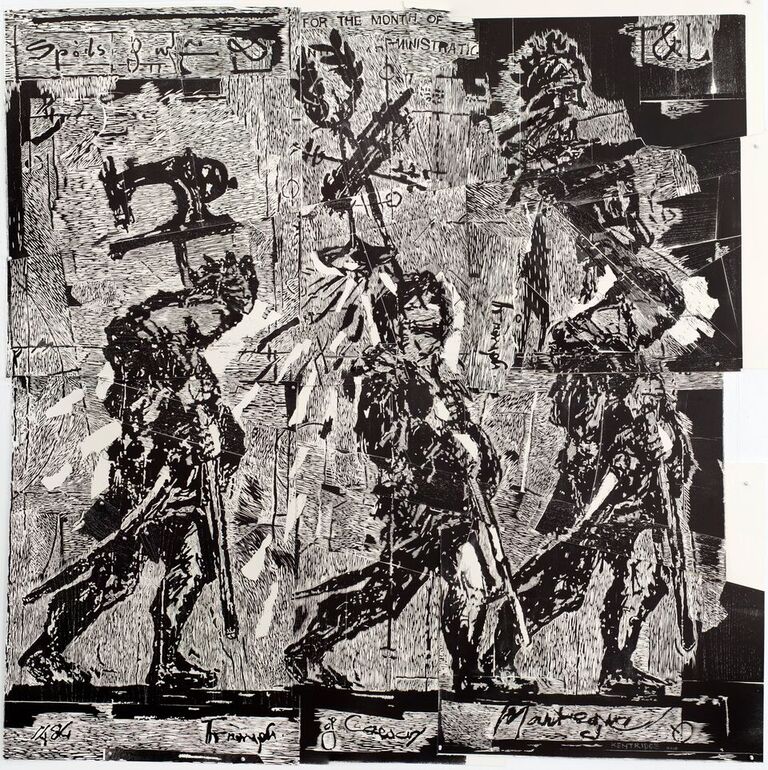

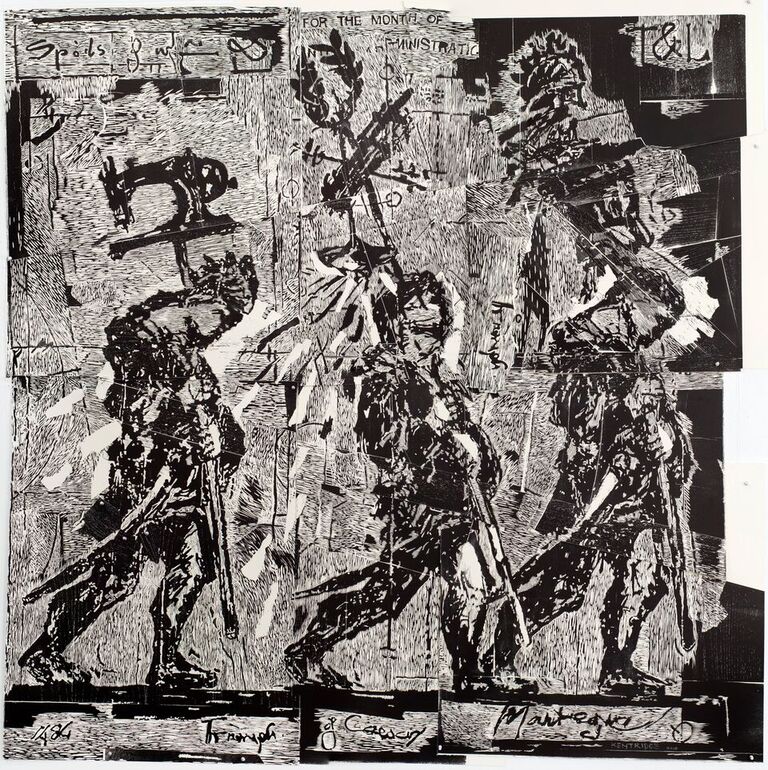

For the woodcut, titled Mantegna, Kentridge extrapolated a scene of three figures from the frieze, which is based on a famous series of paintings by Italy’s leading Renaissance painter and printmaker, Andrea Mantegna. The series is called The Triumphs of Caesar (1484-1492) and depicts Caesar’s army triumphant from battle, parading their spoils of war through the streets of the Eternal City.

This is how Kentridge’s rough, monochrome recreation appears on the Tiber waterfront:

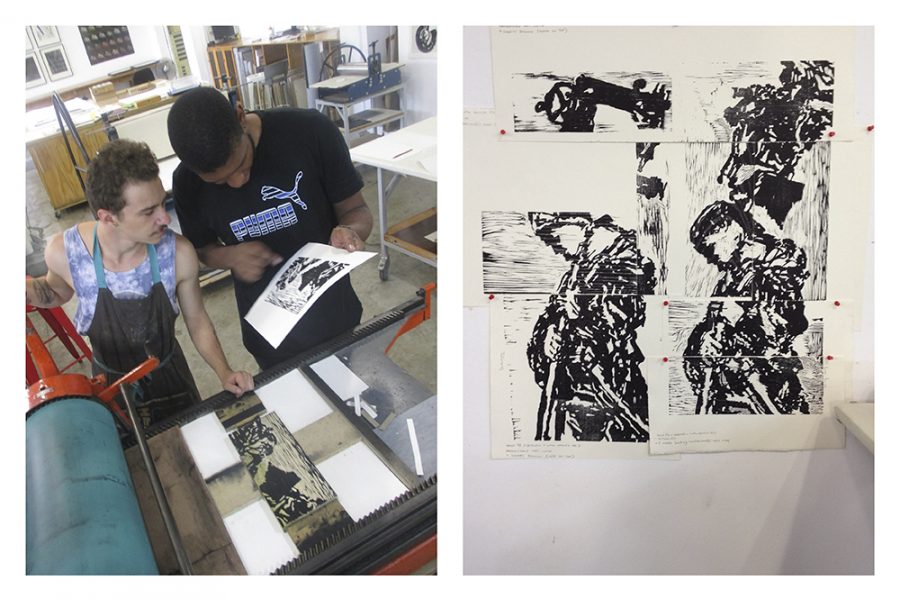

Since January, the printing team at DKW – headed by master printer Jill Ross and her core carvers Sbongiseni Khulu and Chad Cordeiro – have worked round the clock to produce a 2x2m woodcut of Kentridge’s Mantegna image. The result is nothing short of extraordinary:

This blog post maps the trajectory of an epic collaboration, marking the labour-intensive teamwork that resulted in this visceral image.

At the 2015 Venice Biennale, Kentridge presented a series of drawings as a precursor to Triumphs and Laments. David Krut Workshop’s master printer, Jill Ross was blown away by the ambitious scope of the project. She went to visit Kentridge in his studio at the start of 2016, when official preparations for the frieze were in motion.

“The last time DKW collaborated with Kentridge was in 2011 for the Universal Archive linoleum print series, which comprises over fifty images. The project grew and grew and ended up taking four years to complete”, Ross recalls.

“The last time DKW collaborated with Kentridge was in 2011 for the Universal Archive linoleum print series, which comprises over fifty images. The project grew and grew and ended up taking four years to complete”, Ross recalls.

The prospect of collaborating with Kentridge again was invigorating, particularly because he was working in large scale, which inspired Ross to think big in terms of prints.

But, at this early stage, the project moved tentatively. Before deciding on scale, the team would test a range of paper and timbers.

While Japanese rice paper (Chine-collé) is traditionally used for relief printing, they decided on Somerset Soft White paper for its thicker tooth and rich, off-white colour.

Choosing the wood grains was less straight-forward.

Ross advised Khulu and Cordeiro to experiment as much as possible to allow the nine different grains to dictate the results:

“I wanted to allow for potentially strange and surprising results to emerge to help us fully appreciate the possibilities of the material”, Ross explains.

They experimented with wood blocks of varying sizes and tried a variety of carving methods to build familiarity with this tough and unforgiving medium.

At this point, neither Khulu nor Cordeiro had experience with woodcut carving, but they had a firm grasp of linoleum so they were excited to try something new.

While developing their carving skills, the team evaluated how each grain responded to the pressure of the press, noting the differences in print quality between soft and hard woods.

After Kentridge visited the workshop to assess the tests, four grains made the cut: Panga Panga (good for carving intricate details, very hard so prints jet black), Maple (relatively soft and easy to cut, prints a lighter black), Ash (big curves in the grain allow for expressive gesture of line needed in the figures’ faces) and Poplar (loose grain allows for subtle mark-making).

The carvers explain that “with the soft, fibrous wood types, it is not advised to carve against the grain as the block can split, but with the hard, compressed grains, you can impose your line more coherently.” Consequently, the team chose a variety of grains to ensure varied line formations in the final piece.

Next, they try carving on a veneer, but soon run into problems. Due to the thinness of the veneer, Khulu and Cordeiro were forced to carve shallow lines, which meant that the strong graphic quality and ink contrast was lost.

Kentridge wanted to work with wood for its patterned surface, which gives depth to a print in a way that linoleum (a much cheaper material) does not. To maintain this vivid quality, Ross increased the thickness of the veneer from 0.5mm to 5mm, giving the carvers plenty of room for maneuver. To make this happen, bespoke furniture maker Alan Epstein assisted with this part of the process.

At this point, the overall image was envisioned to be around A1 size, but, once presented with the team’s impressive handiwork, Kentridge agreed to up the scale considerably.

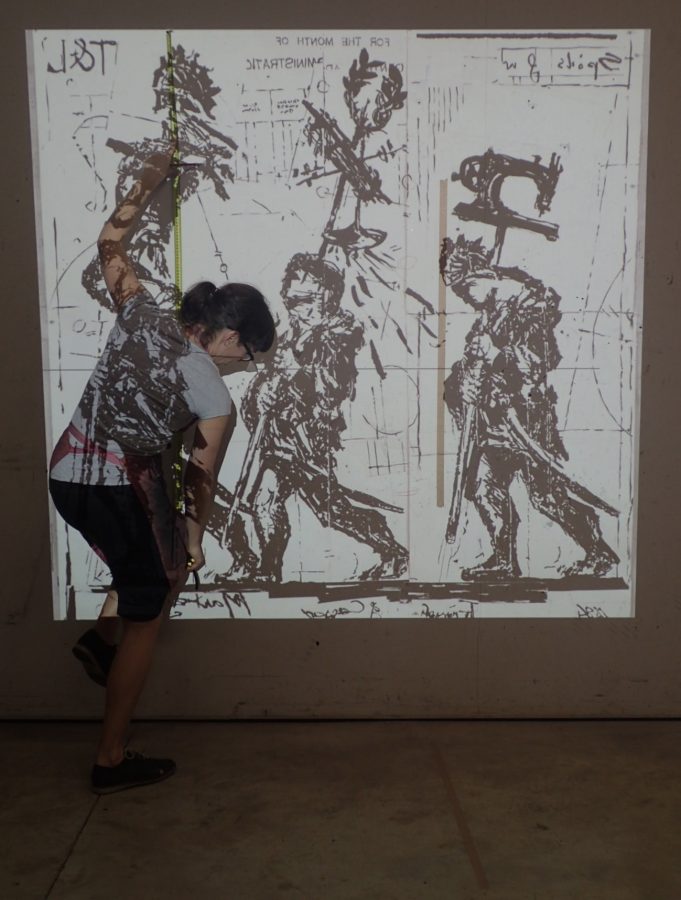

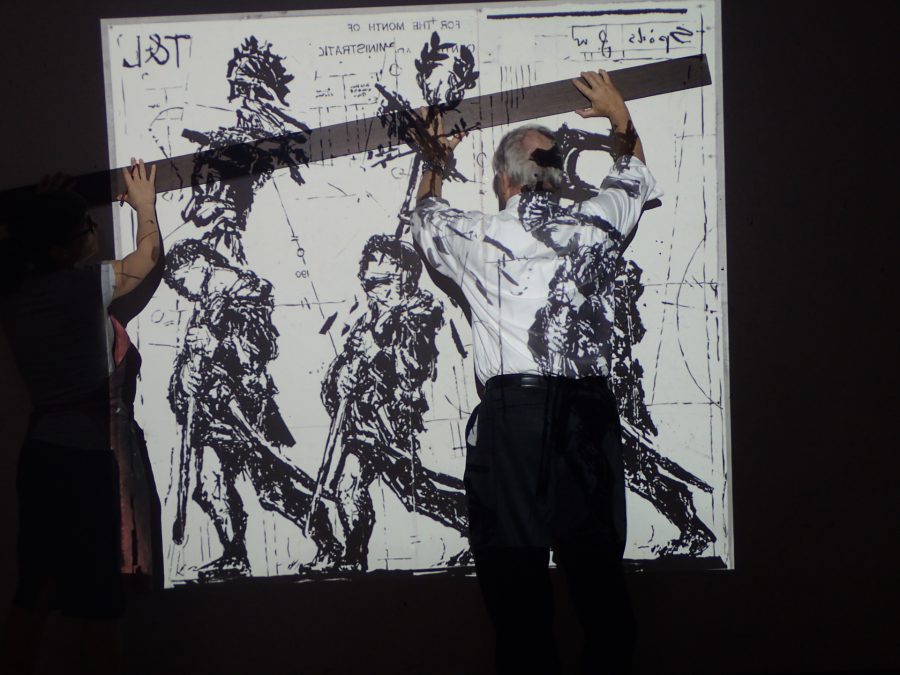

Next, the team moved to Kentridge’s studio where Ross projected the Mantegna drawing to the size of the overall print. At this critical stage, important measurements and arrangements of the different timbers were fixed.

Kentridge also provided the team with a rough sketch of his vision for the wood block arrangements:

Ross, Khulu and Cordeiro then knuckled down to work out paper positioning to ensure that the overlaps would not occur in important areas, like the three faces.

All of a sudden, it was March. They had a month to complete the project.

To manage the magnitude of their task, Ross set Khulu and Cordeiro up with a timer, which meant that every three minutes they would turn the block to carve a different section of the image and respond to a different grain.

They liked the challenge and saw value in the process which allowed for different styles to sit side-by-side: “it kept our technique fresh and makes the overall image read more fluidly”, they said.

The carvers found that as time flew, they grew in confidence, learning to embrace their slip-ups by making them part of the image. They found that if you obsess over small mistakes and try to fix them it doesn’t work and quickly saw that when you loosen up, the process becomes easier and you start to move with, rather than against, the block.

To assist with this painstaking race against time, the team expanded to two more carvers – Neo Mahlasela and Nathaniel Sheppard III, who focused on the thin, detailed marks required in the figures’ faces.

Kentridge came to the workshop regularly to check on progress. During his visit mid-way through the final month, he praised the team for achieving a balanced interplay between intricate marks and wide, expressive gauges.

The team were pumped to push to the finish line. Their pace increased dramatically over the course of the project. It took a week to do the first block, then a week to carve a further two blocks and to start the third and forth and then, in the final week, they carved the final five.

Before jetting off to Italy for the grand opening of the frieze, Kentridge returned to the workshop where he tore up pieces of plain paper as well as discarded proofs and collaged onto the print to create more disjointed line work and to highlight certain areas.

As a final flourish, the carvers needed to create the effect of torn paper fragments raining down the centre of the image. They eagerly embraced the challenge:

At the same time, Ross was busy figuring out how to best arrange the different prints to achieve an exciting overall look to the piece. She played with the puzzle-like nature of Mantegna, overlapping prints in different ways and trying out different borders and paper sizes.

Mantegna has come together out of:

- 12 wood blocks

- 10 printed sheets of different paper sizes plus 10 torn sheets (all pieces overlap)

- 36 pins for paper placement – a characteristic finish to Kentridge’s large prints

Mantegna will launch at New York’s 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair (6-8 May 2016) and at the Johannesburg Art Fair (9-11 September 2016).

For more information on previous DKW-Kentridge collaborations:

http://davidkrutprojects.com/artists/william-kentridge-universal-archive

For more information about Triumphs and Laments and its grand opening: