A profound meditation on Kentridge’s multi-dimensional Magic Flute

(First published in the Sunday Independent of 28 October 2007)

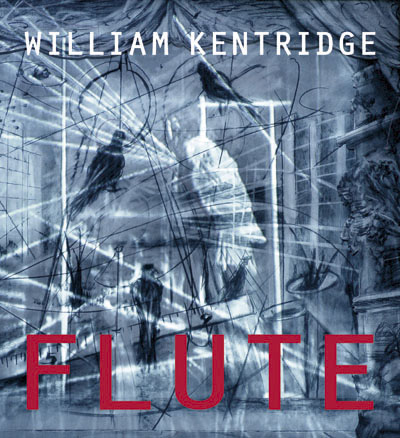

The performances of William Kentridge’s production of Mozart’s Magic Flute have been a triumph in a number of cities in the world, and South Africa has been no exception. Now his Flute, edited by Bronwyn Law-Viljoen, has been issued by David Krut Publishing in Johannesburg. It is a book that is in many respects as remarkable as the stage production. It is more than a record of the production – more, even, than an intelligent, in-depth reflection: in its present form the book is an accompaniment to the production and almost a part and an extension of it, a profound meditation on the entire process involved.

It also moves beyond the strict contours of the stage event and incorporates an account of Black Box, a production that flowed from The Magic Flute and fed back into it. If anybody still had any doubt about it, Flute should now affirm, persuasively and gloriously, that Kentridge comes closer to the prodigious creativity and the promethean energy of Picasso than any other South African artist. And indeed, the way in which he lends a dimension of terror and darkness even to mundane or frivolous aesthetic moments reminds one of the epithet terribilitá used in the Renaissance for the work of Michelangelo.

It is almost 10 years ago, in 1998, that Kentridge was commissioned by the Théâtre de la Monnaie to direct Mozart’s wonderful, dark and enigmatic last opera; and by the time it moved to South Africa (Cape Town in September, Johannesburg in October 2007), Kentridge and his team brought with them all the insights and discoveries gained by productions in a variety of other cities across the world.

Given Kentridge’s way of constantly returning to a work, rethinking, reshaping and even reinventing it along the way, The Magic Flute has by now, in his hands, arrived at a maturity and a multi-dimensionality which makes it a truly amazing experience in which all the senses are involved.

If one has the slightest doubt about any aspect of the project, it might be that local artists involved in the production cannot always match Kentridge’s staggering grasp of visual, spatial and musical experience: in Cape Town, for example, one of the sopranos singing the Queen of the Night, sadly could not do justice to the pyrotechnics of the artist/director’s imagination: this is one of Mozart’s greatest roles, in which light and darkness, good and evil, reason and madness, are all dazzlingly – even frighteningly – intertwined; and Kentridge fully rises to the demands of the composer’s genius.

It happens so often in Mozart that music and words in fact contradict one another, each discovering possibilities and paradoxes of meaning in the other: in Le Nozze di Figaro, in Idomeneo, brilliantly in Don Giovanni, even – exquisitely – in Cosí fan tutte. And Kentridge thrives on such an interplay. His design is clearly not meant as an “illustration” of the opera, but as a tremendously exciting and challenging part of a new whole.

This is what the book conveys with remarkable effect. The substantial interview with Kentridge in the beginning defines the parameters of the project and illuminates the fascinating processes at work in the artist’s mind, in never following one “path” through The Magic Flute only, but simultaneously all the “other paths not taken” within the overall concept of “light triumphing over darkness”, and on a stage that needs no depiction of a cage because it is itself a cage. A cage that, at the same time, offers a liberation, a way out, to the extent that this cage is at the same time a camera which in Black Box develops several steps further.

In this way, Kentridge’s Magic Flute becomes not only a manifestation of the Enlightenment, the period in which Mozart’s opera was created, but also its “underside”. Among other things, this “makes us wonder about the blindness that leads to the disjunction between art and political action”.

The artist’s musing on Zarastro’s Blackboard amplifies the introductory interview, as he tries “to find a vocabulary for the production”, in his movement towards grappling with Mozart’s “mix of the rational, the fantastic and the contradictory”.

From there, we are guided into the production by Stéphane Roussel’s discussion of the opera (“Drawing With Light”), based on La Bruyère’s perceptive comment on the need “to hold the mind, the eyes and the ears in equal enchantment”, and her articulation of the various levels on which the basic tensions are presented and resolved – via the metaphors of photography, colonialism, Egyptian mythology, Freemasonry.

In a brilliant essay on printmaking Kate McCrickard amplifies the exploration of Kentridge’s art (with a particularly illuminating discussion of his handling of the rhinoceros theme).

It is followed by a detailed discussion of the production of The Black Box (in Law-Viljoen’s “Footnote on Darkness”), not as “a footnote to the opera”, but rather as a “dark memorial” to “the strange fruit” of the German colonial endeavour in which “the values of truth, light and rationality” are dissected.

Ultimately, the magnificence of the book lies in its value as a “total production”. The canny way in which visual material complements the erudition and enthusiasm displayed in the text, and the wonderful way in which the book functions as a “companion” to the opera production.

It is indeed a rare pleasure to study it over and over again, marveling at the artist’s ingenuity and the each of his imagination (which is always founded within the reality and the dazzling possibilities of the stage and the opera) – and also at the beauty and inspiration obvious in the composition of the book.

© Andre Brink, Sunday Independent 2007