04.10.16

This conversation accompanies SUNSETS – a series of 6 drawings in lithographic ink on paper by Jacob van Schalkwyk – shown at David Krut Projects in Cape Town from 17 September to 22 October 2016.

Topics Covered:

Colour / nature / layering / fire / control / futility / topography / category / theory / inspiration / expiration

Jacqueline Flint– Have you always been comfortable with colour?

Jacob van Schalkwyk – I think I only became comfortable with colour after moving to Cape Town from Johannesburg. I found a bachelor flat on Beach Road across from the puttputt course. It was cheap because the windows leaked when it rained, but the view was enormous. It was a big change from Johannesburg and New York. Just looking at my address used to crack me up: 9 Dolphin Bay, 169 Beach Road. So I lived and worked in this tiny space by the beach, watching sunsets and really getting lost in colour.

All my work from the moment I moved to Cape Town…colour was just everywhere.

So you moved closer to nature and your work exploded into colour, and these works signify that move.

Absolutely. Definitely landscape-influenced, although I don’t look at them as pictures of landscapes.

I don’t think one can call them pictures of landscapes either, but to me the surfaces are built up like mountains or hills and valleys.

Kind of topographical, like contour lines.

Yes, exactly.

When I was a kid, we used to go hiking and if you hiked a 5 day route you’d get issued with a contour map. That was a very special map because you’d whip it out when you needed to know exactly where you were in relation to things like water or shelter. Or if you’d lost the route, the topography would help you situate yourself. I do see them as topographical.

They are heavily layered – that can be seen at a glance. When you are making them, do you start with one colour as a basis and then work up in response to each colour as you go?

In these drawings, on a technical level, there has to be a base colour because there are going to be such heavy layers where I leave the ink to coagulate. I think those layers reach a surface that approaches low relief, really. Because there is so much weight going onto the paper, there needs to be a base layer of ink to reinforce or help the internal and external sizing of the paper, so that the ink – which is oil based – doesn’t ever make contact with the paper fibres, thus destroying the drawing. So there has to be a preparatory layer: the ink must first be lain down thinly. I start by rolling. You’ll see that all of these have a rolled layer.

I’m interested in always keeping the substrate visible, like Michelangelo taught us, you know, not to close up the form completely. This approach also allows for interesting viewing, I mean where and how the viewer is allowed into the picture. Once the drawing reaches a certain weight, the heavier layers of ink refuse you access into the drawing, whereas you can still get in under the bottom layer, wherever the substrate is visible. There have to be places where you can get in. I want the viewer to be welcomed into seeing the entire history of the drawing, beginning with the paper itself.

Once you’ve created your support – which is ultimately also your access point, and I like that very much – do you respond intuitively from that point onward?

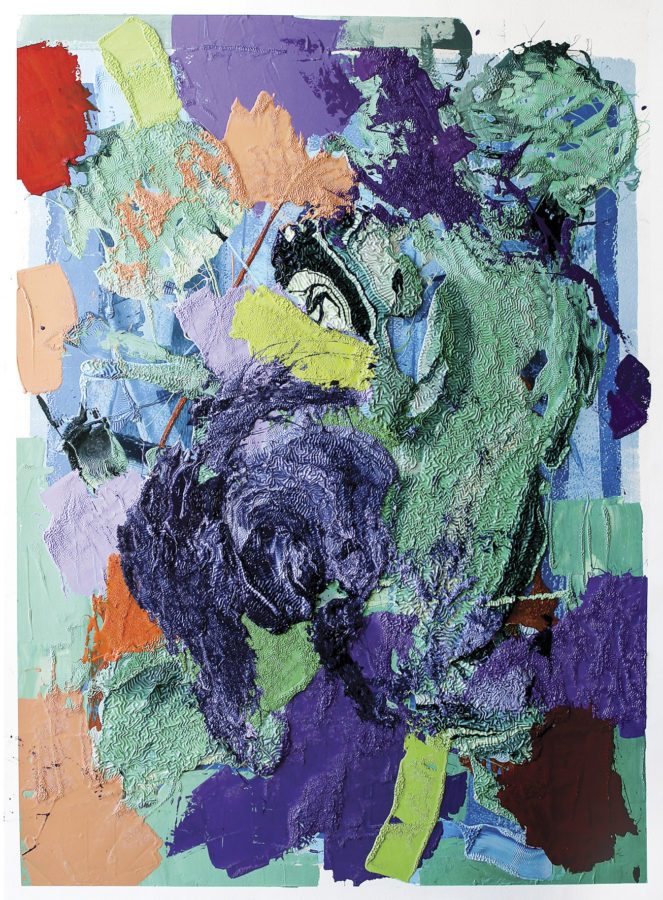

Sort of. I mean I can’t actually completely relinquish control of where I put something. In these drawings I try my best to be callous and not caring in the laying down of colours. These colours are mostly excess colour from my Colour Project so the colour that is available is the colour that was mixed on the day, and then because I work in multiples I decide to put the colour on certain drawings. In these “Tumult” drawings, the palette is very limited.

Even though there’s huge variation in steps in colour, it still is just blue and green, whereas with the other ones there’s no limitation on the palette. Once I get to these low relief layers, there is gesture. There is intent to create some sort of a varied dynamic composition. This is Delacroix, right? I mean the kind of circular composition, the spiral: it’s not chaos, it’s just dynamism.

There’s compositional movement, and also real movement, physical movement in the making of the work.

Yes. I guess the point is that there is an event. There was an event, this is an event, that drawing is an event. Each mark is an event. And if they are built up over 3 months but they end up with one almost cocky gesture, there’s a tension there that’s really exciting. Like, go ahead and screw up 3 months of work…or it works out.

It looks like most of the time it works out, but I get that you never actually know whether it’s going to…

Yes. But you know it’s wonderful you read them as landscapes because they are landscapes on the level of form.

They are concerned with the generation of form and my reference is the environment that I live in. So this one, “Regrowth”, for example… There was that big fire last year, the Silvermine fire, the whole Southern Peninsula area was burnt down and so I rode through there on my motorcycle immediately afterwards and there was nothing. And then a week later you do the same trip and there is this green.

This green?

Yes that green, immediately.

Then the wild flowers come in.

And the Fire Lilies. This colour here is as close as I can get to the Fire Lily… But it’s not about resilience. Without making any kind of moral or ethical judgement on things or on how things go, shit just happens like that. Things burn down completely. There is so much that happens in society that is so disgusting to witness, and it feels like you’re completely burnt or your constitution is burnt, and then there seems to be no culpability. Culpability is something that seems to no longer exist, so you feel like injustice is triumphing.

It’s the fire. But in nature, within a week these wonderful things come back yet it’s neither optimistic nor pessimistic. It’s just growth, it’s life.

It’s the next cycle.

I spent a long time last year trying to – again – figure out what the hell does it all mean if… you know… as an individual making art… What’s the point? Where does art fit in, if at all? 2015 was one of those years. So I made four large drawings called “The Futility of Action” where I drew my way through that question. And those drawings freed me up in many ways to work with futility.

And, wow, there’s a huge amount to work with! Then, letting go of that pressure, I mean, whether one feels a sense of futility or not, things just continue to come in and out of being. The less you try to get involved making decisions or judgements about what is good and what is bad, the more free you are to make. You just have to adapt. And I approached these drawings that way.

That relinquishing of control mirrors your walking quite untethered into colour.

Yes, that, and also in the mark-making on these.

I’m not making these thinking about composition or picture at all, they’re just generated by almost flippant afterthoughts of laying down excess colour.

Also the drying of the ink and the patterns that form as a result of that – you have absolutely no control over that either.

No.

It just does what it does. This is why mountains form like fractals: this drying ink is that same force on a small scale. You’re working with the microcosm of a force that creates mountains.

DRAWINGS

Somehow, I always end up encountering this meeting of landscape and language and identity. I think it extends all the way back to my studies. I wasn’t really interested in art then. I was a literature graduate and when I was doing post grad, I was fixated with Michael Ondaatje. Sure, “Coming Through Slaughter” is an amazing book.

I was obsessed with his work, particularly with “The English Patient”, but I’ve loved deeply everything he has ever written because he manages to hook deep into feeling, using language. A lot of writers do that, but I was interested in the mechanics, what is it about Ondaatje’s language that does it? Because his language is very slippery, actually. So is it because it’s so slippery that it hits you in the chest so hard? I never finished that post graduate degree because a friend of mine died. The landscape, the language, and the relationship between landscape and language and trying to locate my altered self within all that…

I just couldn’t find my new self. So I extricated myself from that landscape in quite a violent way and now what keeps coming back is this idea that the construction of self, the landscape and language can’t be separated out very easily. Identity is topographical, as far as I’m concerned.

Well it’s a very interesting statement. I have lots to say about being torn from the fabric that was up until then your life. That is something that Ondaatje does in “Coming Through Slaughter” really clearly, that being torn is a generative force of jazz, and our culture is about those moments, about being torn.

We’ve returned to the fire.

Yes. You speak about being violently relocated. There’s a lot there that has to do with how we define ourselves as citizens of the world at the moment. Everybody’s being torn asunder from everywhere really. I think that looking at identity from the topology or the category theory side is very interesting because for so long identity has been defined as a set of internal attributes, extensional attributes.

We look at things in terms of variables. The identity of something is: there are x number of cups in this room and things qualify as cup because they have these attributes. So let’s say the room is a state of affairs. We look at the state of affairs in terms of the contents of the state of affairs, the identities that make up the room. Whereas if we take a topological or category theory approach to this state of affairs we’re not going to try and count the number of objects or forms, we’re going to rather look at the relationships between them.

So you can see that computationally this is much more complicated because we are only looking at morphisms, which are the connections or the ideas between my cup and your cup. So we’re calculating a vast amount of information and deducing that there are two objects in this room. After much computation we can say those two objects happen to be cups, but the dynamic, fluid nature of this space is not defined beginning with the objects themselves. They are really fleeting and event-based.

They become deductions of a dynamic.

So you might have a slightly different dynamic on a different day and you might come to a slightly different deduction, which still is a cup.

Yes, and by doing that we get to look at things in a vastly different way. It’s a radically different way of seeing. So then the thing is, how do we see our state of affairs, our surroundings? How do we come to knowledge and how do we find things and how do we find identity with this way of seeing? It redefines our understanding of things like identity and difference – and the relationship between them.

And it sort of reorganises those things in terms of priority. In this way of seeing, identity becomes subordinate to difference and that is a big deal, it’s a big leap to make.

That identity is subordinate to difference… And we come back to the beginning, which is how the ink on a roller or a tin lid, some excess colour suddenly means something different when it’s put down in relation to a bunch of other marks on paper, which themselves mean something only in relation to each other.

It’s not the identity of the marks themselves that’s important. It’s that they’re all in it together, the same state of affairs. They are in a covenant with each other with a specific outcome in mind. And I think in these works, that outcome is really viewing pleasure. You know, sustained joy.

EPILOGUE – A SNIPPET OF CONVERSATION …and at 3 in the morning, oh my god, it’s like this night is never going to end. On the one hand time is just racing so fast and then on the other hand there are moments inside days where time just stretches out. It’s so bizarre, it’s a little bit like being in a Dali painting.

3 o’clock in the morning is the devil’s hour, that’s when it strikes: at 3.

You know that in traditional Chinese medicine, 3am to 5am is the portion of the circadian rhythm that’s governed by the lung meridian organ system, which relates to death; expiration, but also inspiration at the same time.

On a hospital ward, they call it The Death Watch shift because a lot of people die between 3 and 5 in the morning. My son (he’s eight months old) is up most of the night, but if he is going to wake up and stay awake it will be at 3am. So I am always very alert at that time. And always at that time the dogs will get up and wonder around the house. My husband will stir more than usual in his sleep. You can feel that it’s 3am without looking at the clock. Something funny happens.

It does. And one of the things that happened at 3am was that Metallica composed “Enter Sandman,” the riff.

People ask me a lot about where do you find your inspiration and inspiration is interesting as a conversation when you reference Agnes Martin. Her approach to inspiration is pretty astounding, you know: “I’m an empty mind. When something comes into it, you can see it.” To me she is a major inspiration. I love her work. That kind of inspiration and the relationship we have with ideas and the time that these things come… 3am is one of those times where things come to you. I work day shifts. I don’t work through the night anymore. I’m busy working on something else during the night. I don’t want to be in the studio at 3am.

I want to be in my bed or my home open to those kinds of things coming.

Those inspirations, and maybe sometimes they are expirations too.

It’s like clockwork. It is 3am and you can work yourself into a stupor by 2am and go to bed and miss 3am and then I don’t know what you’re going to make. You’re going to make lots of shit art.

Well, maybe he’s onto something, that baby.

He’s definitely onto something, he’s trying to live.

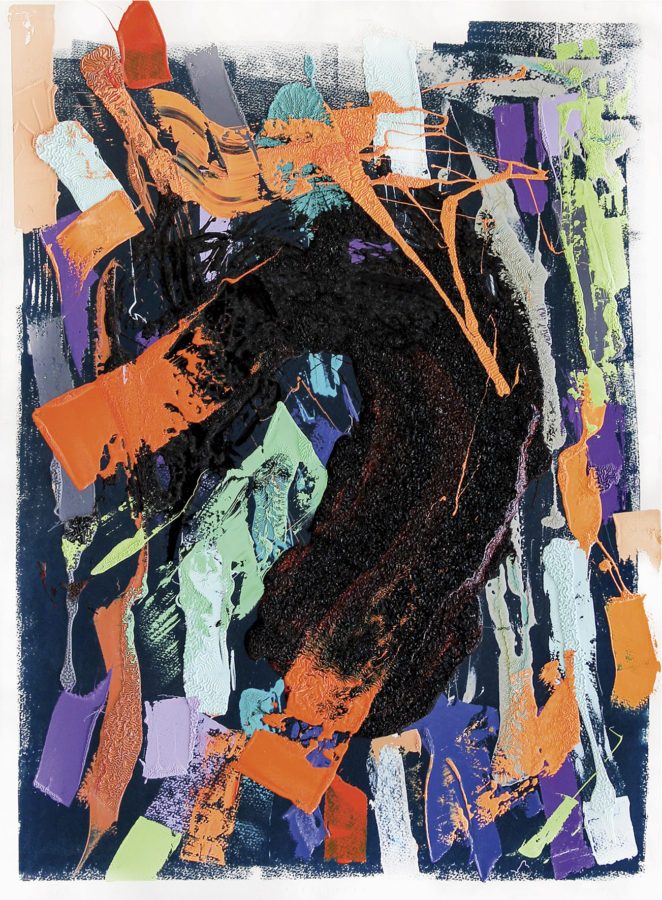

And then those things that come out of being… That work, “Putrefaction: Sunset Sandy Bay”, over there. The process of the decomposing of the body and decomposition: it’s quite colourful. It’s very colourful what happens to the body or to form when it decomposes.

When it’s exiting, post-expiration.

As much as a study of anything else, it’s an anatomical study. We can spend time with forms that have expired. Because they’re not moving, we can understand them. I was reading about Cézanne the other day.

Julian Barnes writes about how Cézanne treated his models and if somebody moved he would go into a rage – you’ve ruined the pose, you know. The whole thing about painting card players is because the card players wouldn’t move much. So you have to have this lack of motion to be able to understand the motion of the organism. Once it’s expired there’s opportunity for a clearer understanding of the workings of something when it was alive. There is the erotic of the process of decomposition, that the impetus towards propagating life, sex, is not about affirming the fact that we are alive.

We want to fuck each other because we want to feel death, the presence of death. That is what gets us aroused. Or at least, that’s what got Bataille aroused.

There’s that word in French: “jouissance”, which means “enjoyment” or “excess of life”, but somewhere in Lacan jouissance as a concept is the death impulse as well. It doesn’t exist in a binary way. Orgasm is also “little death” in French, it’s “la petite mort”.

I heard that, yes. But they’re very cultured and stuff, they probably figured this shit out a long time ago.